Age of Invention: How Coal Really Won

The Coal Conquest, Part II

You’re reading Age of Invention, my newsletter on the causes of the British Industrial Revolution and the history of innovation, which goes out to over 38,000 people. To stay tuned and support the project, subscribe here:

Over the course of 1570-1600, people all along the eastern coast of England, and especially in the rapidly-expanding city of London, stopped using wood to heat their homes. They instead began to burn an especially crumbly, sulphurous coal from near Newcastle in Northumberland — a fuel whose thick, heavy smoke reeked, stinging their eyes, making them wheeze and cough, and tarnishing their clothes, furnishings, and skin.

As I set out last time, the usual story — that this was caused by deforestation, making firewood so scarce that people resorted to burning an inferior but cheaper fuel — simply does not stack up. England’s deforestation — along with the draining of its peat-filled fens and marshes, and the clearing of its gorse-growing heaths — was instead itself caused by the arrival of cheap coal. Coal freed up huge tracts of land that had been set aside to warm the hearths of people’s homes, allowing them to be used instead for crops or pasture — food to fill the bellies of man and beast, and make England extraordinarily abundant in muscle.

By the 1780s even the visiting son of a French duke was astonished at the large and varied diets of English people working in factories or down mines. He was just as impressed — like a visitor to late twentieth-century America seeing the sheer scale of car ownership — at the number of English horses, estimating that “in proportion to the inhabitants, I think the number of horses in England must be double that of France.” English gentry families each had at least three — two to pull a carriage, and another to ride. But what truly inspired awe was that even ordinary farmers could spare at least one for merely riding to town or market, rather than having to tether them all to the plough.

English horses were also all of an astonishing power and size — “in France we have no idea of their quality: all tall, well-made”.1 London’s industries in the eighteenth century — fulling cloth, pumping up the water supply, pounding rags into paper, flattening metal into sheets, boring pipes and guns, grinding the pigments for dyes and paints, tobacco for snuff, charred bones for shoe polish, tannin-rich oak bark for leather, flint for glass and ceramics, and grain for flour, beer and spirits — were overwhelmingly powered by horse. Many more hauled the city’s goods and people too.2

But if deforestation and the resulting expansion of both tillage and pasture were not the causes of coal’s rise, and merely one of its dramatic consequences, what was its cause?

Home is where the Hearth is

The most influential alternative theory is that in the mid-sixteenth century the English invented better ways to burn coal in the home. To remove coal’s most noxious effects, the smoke could be drawn up and out of a room by burning it under a chimney. Chimneys were already becoming common long before coal-burning became widespread, especially in towns and cities with multiple-storey buildings. Out in the countryside, a typical single-storey home could burn firewood in an open central hearth, allowing the light smoke to rise up into the large space beneath its tall-set rafters, and to dissipate through unglazed window holes, or through an opening in the roof. Adding another storey, however, as in cities, tended to lower the ceiling of the ground floor considerably, leaving little space for the smoke to dissipate to, while the occupants of a second storey also needed to be able to breathe fresh air. So wood fires in multiple-storey buildings were increasingly lit under a hood or mantle, the smoke venting through a chimney outside. In the 1570s the chronicler William Harrison noted how one of the great changes of the previous decades was “the multitude of chimneys lately erected”.3

But hearths and chimneys suitable for wood fires were not, by themselves, suitable for coal. Wood-burning hearths were often built wide, with the chimneys merely providing a passage through which to vent outside. But coal fires needed the hearth to be compact, and the chimneys to actually lift a much thicker, heavier smoke, which would otherwise suffocate the room. As a result, burning coal needed a much narrower hearth, and for the chimneys to have a more powerful draught by being both tall and narrow. Unfortunately, a strong-draughted chimney also took a great deal of the heat out of the house along with it, and the draught sometimes even needed to be helped along by keeping a door or window open to the cold outside.4 So a cast iron plate, or chimney back, had to be placed behind the fire to try and reflect some of the heat back into the room.

Yet even with a suitable hearth and chimney, coal fires also required a means to keep the coals heaped together while allowing air in at all sides, and for the ash to fall away rather than building up until it smothered the fire. One suggestion in 1603 involved using a loose stack of bricks, with iron cannonballs placed amidst the coal.5 But the ideal method was to use an iron fire-grate — a kind of iron basket raised off the ground — which allowed one of coal’s big advantages to shine through: once a coal fire got going, it needed far less time and attention than when burning wood. “I prefer coal to wood,” noted a foreign visitor in the eighteenth century, though only after they’d become accustomed to the soot and smell, “because one isn’t constantly having to mend it”.6 Provided you had the right kind of building and equipment, replacing wood with coal was an early tedium-saving invention for the home — the washing machine or dishwasher of its day.

It’s certainly plausible, then, that England’s shift to coal was helped along by the widespread adoption of chimneys and grates. Here was potentially a new set of technologies to increase the demand for coal in people’s homes, like how the invention of the car increased the demand for oil. And as the economic historian Robert Allen argues, the rapid expansion of London in the late sixteenth century may have provided both the opportunity and the means. Londoners’ growing wealth allowed them to afford the new iron grates and chimney backs, while the quadrupling of the city’s population meant that builders could introduce coal-burning chimneys into the city’s growing number of homes, making coal a commonplace even before any of the older homes needed to be retrofitted. Having been adopted in London — “the laboratory that brought coal into the home” — Allen suggests that the grates and chimneys then spread elsewhere.7

I had long believed this narrative, and have even helped spread it. See, for example, this piece I wrote last year. I’d always intended to look deeper into it, however, as I’ve never been a fan of vague stories of adaptation, or of invention simply springing forth due to need. So I set out to find exactly when the changes occurred, and who was responsible. Someone or some group of people were the inventors and adopters, and I intended to find out who they were.

But in doing so, I kept discovering a steady drip of annoying facts that simply did not fit. And so I now have to conclude that this wasn’t at all how coal use first spread.

Some Inconvenient Truths

The first annoying fact is that the coal-burning house was significantly older than the mid-sixteenth century, and had been invented not in London, but in the places — unsurprisingly, really — hundreds of miles up the coast, where the coal was dug. By as early as the 1300s, for example, monks at Durham, at Jarrow on the Tyne, and on the isle of Lindisfarne, were already using chimneys and iron grates to burn the very same sulphurous Northumbrian coal.8

And there’s plenty of evidence that coal continued to be burned in the homes of people near to where it was mined. Foreign visitors to Britain always remarked on the burning of coal because it was so unusual, but they never mentioned London in this regard — not until much later. A visiting Venetian in 1551, for example, reported that it was in Scotland that “they burn stones … of which there is plenty”,9 while a Frenchman in 1553 remarking that the Scots “do not warm themselves with wood, but with coals.”10 A 1556 description of England drawn up for queen Mary I’s new husband, king Philip II of Spain, the north was likewise described as a place where “they burn a certain hard, black stone mined from the earth, which gives a great deal of heat, and which they call ‘sea-coal’”.11 We can also just look at a drawing of Newcastle in 1545 to see that every single home had a chimney, almost certainly for burning coal:

By the 1570s, too, when there’s still no mention of coal being burned in the homes of Londoners, it had apparently already become one of the main fuels of Dublin and the Isle of Man, likely supplied from the coal mines of Cumbria, as well as near the coal mines of inland England and southern Wales.12 And much the same could be said of coal mines abroad, such as in modern-day Belgium. A Greek visitor to Liège in 1545 remarked on how “in this city and all the neighbouring country they are accustomed to burn a certain black substance, stony and shining”, visiting the coal mines and describing them at length. But he doesn’t mention any coal being burned in London, which he visited next.13

The very first hint of coal’s rise, cited without fail by all historians who discuss it, comes from a work published in 1577 by the chronicler William Harrison. In the process of lamenting deforestation, he mentions a long list of fuels, including peat, gall, reeds, rushes, straw, gorse, furze, heather, bracken, and even tufts of grass, as well as coal, which were “to be feared … will be good merchandise even in the city of London”. But if we read this carefully, he only says that they might eventually be resorted to in the city if the trend continued, not that they had already become common. And while he does then say that some of these fuels had already arrived in London and “gotten ready passage and taken up their inns in the greatest merchants’ parlours”, he never tells us which. Coal may or may not be one of the few. Given his mention of new fuels making their way into the living rooms of the rich, who decades later were still the remaining holdouts against burning coal, I’d say it’s much more likely that he’s actually referring to twiggy plants like gorse or heather having started to replace the more smokeless, luxury domestic fuels like charcoal.14

Indeed, Harrison is much more explicit in noting that coal was already one of the main fuels being burnt, not in London, but in Cambridge,15 having been shipped from Newcastle to King’s Lynn, and then up the River Cam. So what he actually tells us is that the burning of coal in people’s homes was in the 1570s only beginning to creep down the coast from Newcastle, where it had already been in use for over two centuries, reaching the hearths of Cambridge, about 300km away by water, before it reached London, which was 550km away — almost as far again. Rather than being pulled by a growing London’s demands, coal was instead pushing its own way out of Newcastle, finding new markets by itself. Much like the visitors’ reports of the 1550s, detailed descriptions of London by a visiting Frenchman in 1578 and by a German in 1584 still made no mention of coal being burnt in people’s homes at all.16

Far from being the laboratory that brought coal into the home, then, London was actually a laggard — all the more so given it had been buying coal from Newcastle for centuries. The city had long imported some coal to make lime, used in the mortar of its grander buildings made of brick or stone. And coal fuelled the forges of its blacksmiths, “to soften their iron”.17 As the Venetian ambassador in London put it in 1554, coal was “extensively used, especially by blacksmiths, and but for a certain bad odour which it leaves it would be yet more employed”.18 By the 1560s the city’s blacksmiths were regularly consuming about 10-15,000 tons of Newcastle coal per year.19

Coal for the forge, however, did not automatically lead to coal being used in the home. Otherwise our story would be focused on the Low Countries (modern-day Belgium and the Netherlands) or northern France. Writing to government ministers in 1552, an English merchant proposed that the export of coal to France be controlled. Newcastle coal was, he said, “that thing that France can live no more without, than the fish without water”, because without it “they can neither make steelwork, nor metalwork, nor wirework, nor goldsmith work, nor guns, nor no manner of thing that passe the fire”. As soon as the fishing season was done, he said, dozens of French ships from Normandy and Brittany descended upon Newcastle to buy up coals for their smiths back home. Having traded on and off with France for almost forty years, he had even profited from its demand for coal himself.20 When in the 1570s Harrison recounted how coal’s “greatest trade begins now to grow from the forge into the kitchen and hall … in most cities and towns that lie about the coast” — the passage that historians always love to quote — this was only after noting how they were “carried into other countries of the main”.21 Coal’s creep into the homes of England’s coastal dwellers may have been remarkable, but it was still mainly a commodity exported to smiths abroad.

So if the coal-burning home had already been in continuous use elsewhere for at least two centuries, in which time London had imported coal for its smiths, why then by around 1600 had it so dramatically made the switch?

Allen argued that London’s growth in the sixteenth century had put pressure on the city’s supply of firewood, making it so expensive that coal looked sufficiently cheap to prompt the switch. But as I noted last time, demand for fuel in the early 1300s was even more intense than on the eve of coal’s rise. London’s population in the mid-sixteenth century was only about 50,000, compared to a much larger 70-80,000 in the 1300s. And even when London’s population began to exceed this in the late sixteenth century, the medieval city had had to draw firewood from much farther away, cropping nearby woodlands much more intensively for fuel.

A potential answer to this is that the London of the mid-sixteenth century was much wealthier than that of the 1300s, even if it wasn’t much larger, and so might have better afforded to make the switch. Supposing it was wealthier — and we don’t really know if it was or not — the switch to coal was certainly expensive. It required hundreds of thousands of households, most of them of only modest means, to invest in buying a grate made of expensive wrought iron, in a chimney back made of cast iron, and to make extensive alterations to their homes using stone or brick. Even houses that already had a chimney — London was regularly drawn with plenty of chimneys before it made the switch to coal, because it had so many multi-storey buildings — would have needed to narrow their hearth, and either narrow or heighten their chimney flue too. Like installing gas boilers and central heating in the 1970s and 80s, or a heat pump today, the switch to coal did not come cheap, and so a wealthier London may well have been better able to make the change.

But, if anything, a wealthier London would have made the switch to coal less likely, not more. Unlike the shift to central heating, which for the first time made bedrooms and bathrooms warm enough to bear without being covered in layers of clothes, the switch to coal involved both considerable up-front cost and a loss of comfort rather than a gain. (The convenience of not needing to spend quite so much time tending a coal fire than a wood one would only really be appreciated later, once the coal-burning home had become widely adopted and it was too late to go back.) A wealthier London could have simply drawn its firewood from slightly further away, as it did in the 1300s. And as we saw last time the sustainable production of firewood could readily expand to meet demand. A wealthier London would have had the means to avoid making the switch to an inferior fuel. Coal was at first the fuel of servants and the poor, only more gradually making its way into the hearths of the rich.22

So if coal’s conquest was not launched from Londoners’ homes, and cannot be explained by a shortage of wood or by the growth of the city’s population or wealth, where then did it start? What I’ve unexpectedly discovered, when carefully sifting the precise sequence of events, and by reading many of the archival sources for myself — one of the main reasons for the long delay in writing this piece is that I first had to teach myself to read sixteenth-century secretary hand, in which most of them are written — is that coal’s conquest was actually launched instead from Germany.

The Wood-Saving Art

Unlike in England, in Germany supplies of wood fuel really did feel the strains of increasing demand. Lacking England’s long coastline, many centres of population and industry in the German interior could not so easily import more wood from further afield. In 1617, for example, when the salt springs of Reichenhall wanted to expand production, the brine needed to be piped for 30 kilometres, and pumped over a mountain, in seven stages, to a height of 300m, just to get to a forest where there was enough wood fuel to evaporate it into salt. It was in inland Germany that the pressures to save fuel, and to invent new ways of doing so, were at their most intense.23

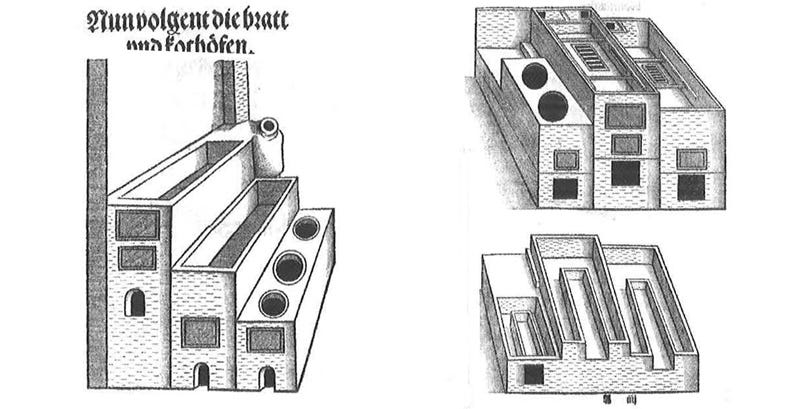

At Strasbourg in the early 1550s the carpenter Friedrich Frommer and the Swiss Protestant preacher Konrad Zwick, a religious refugee, both invented a process to significantly save on wood fuel. Quickly joining forces, they began to stage demonstrations of their process in dozens of cities, raising capital from investors and publishing a catalogue for their customers, which helpfully gives us lots of detail about the invention. Calling it the holzersparungs kunst — the wood-saving process, or art — it came in various forms. It could be used for various industrial processes, like making soaps or dyes or brewing beer, while in the home it could be used in the kitchen or for heating rooms, for which they suggested installing one of their stobenofen, or stove-ovens, which could be lavishly decorated with ceramic tiles. What the holzersparungs kunst always involved, however, was to separate the flame and smoke from whatever was being heated, warming things indirectly via the pipes of the flue, and recycling some of the heat that would otherwise have been lost in merely venting smoke — a method that saved about a third of the fuel.24

The demonstrations were wildly successful, and Frommer, Zwick, and their partners were soon sending agents throughout Europe to get their invention protected by patent, eventually getting monopolies covering Strasbourg, various Swiss cities, the Duchy of Saxony, and even the entire Holy Roman Empire. And probably even further afield. When Zwick died in 1557 — his share was inherited by his young son, but administered by a Protestant pastor named Jakob Funcklin — the wood-saving process was said to have received patents “from emperors, kings, princes, and republics”, and to have already spread as far as “Rome and Constantinople”.

This may not have been mere exaggeration, as we do not yet know the full scale of their operations. The consortium did not always patent under their own names — patents were often only granted to a country’s residents, or at least to someone who was physically present to petition its ruler — and unless we have surviving correspondence with their agents, we cannot always tell for sure if very similar-sounding inventions were actually theirs. For example it’s only thanks to a few scattered references in the well-known letters of a much more famous go-between, the Swiss Protestant theologian Heinrich Bullinger, that we know they sent an agent to Poland, who managed to secure a patent to cover the distant Grand Duchy of Lithuania. The reference to Rome suggests that they may have secured patents in Italy, too, and I’ve seen some historians suggest that they obtained patents in France, though I haven’t been able to chase the source and confirm this for myself.

Given this range, it’s highly likely that they attempted to patent their invention in the Habsburg-ruled Low Countries, too. A wood-saving method patented in the early 1560s by Jan de Jonghe, known as Doctor Junius of Antwerp (more on him later), sounds quite similar to the Frommer-Zwick invention. As does another, patented in 1568 by a Willem Aemissen, citizen of Leeuwarden, which saved fuel by a suspiciously similar proportion of a third. (I hope that this will prompt someone in Belgium or the Netherlands to look into the potential connections.)25

But most importantly of all, the invention seems, with great difficulty, to have eventually made its way to England.

The German Connection

The first hint comes from a patent in 1557 — one of the first ever granted for an industrial invention in England, but which I don’t think has ever been noticed as such before26 — to a John Herdegen, citizen of Nuremberg, for a “new fashion of making all sorts of furnaces” for the use of brewers, dyers, soap-makers, and salt-boilers, “with much less firewood than is presently expended.”27

Herdegen was well-known to the English government. Back in the early 1540s, appearing in various records as Hans Hardigan, Herdygen, or Herdyger — Hans being short for Johannes, the German form of John — he had been recruited from Nuremberg, the European capital of metalworking, as an expert prospector for ores. In February 1545 he had been appointed Henry VIII’s “master of the assays of our mines” at a substantial salary of £40 per year, and a few months later was sent over to Ireland to lead the search for precious metals, reporting back a year later that he had struck silver. That silver, at Barrystown near Clonmines, in county Wexford, was exploited a few years later — again using experts from Germany — and turned out to not be worth the cost. But Herdegen’s role seems to have been over, and by then he had presumably returned home.28

I have not yet been able to track down the movements of Johannes Herdegen over the decade that followed his trip to Ireland, but by 1557 the Frommer-Zwick holzersparungs kunst was already rapidly spreading throughout southern Germany, and it received its Empire-wide patent in the early part of that year. Whether the consortium had yet sent the invention to Herdegen’s native Nuremberg, we don’t yet know, but his connections would have made him an obvious choice to be their agent to England. And so towards the end of the year, presumably after a lot of travel and negotiations, he managed to secure a monopoly on the wood-saving process in England for the next five years.

Unfortunately, we may never know whether Herdegen actually managed to introduce the invention. After the patent itself, he suddenly disappears from the record again. He may never have come to England to put it into effect. And if he did, he may not have had much chance. He may even quite simply have died, as over the next couple of years a deadly strain of influenza — England’s deadliest pandemic since the Black Death — quite literally decimated the population, killing off so many of the parish priests who kept the burial registers, and even sometimes their intended replacements, that the records often suddenly went silent.29

But just two years later, the holzersparungs kunst pops up again in a petition to Elizabeth I by a Protestant from Trento in northern Italy, Jacopo Aconcio, who had fled religious persecution first to Swizerland and then Strasbourg — exactly the same places and social circles as his co-religionists Zwick and Funcklin — before being hired by the English government in 1559 as an expert on fortifications. Within months of his arrival, Aconcio was asking the queen for a monopoly over some designs for a windmill able to automatically turn into the wind, for a mill moved by non-flowing water — perhaps an early atmospheric steam engine — as well as for “a new design for building furnaces for dyers and those who make beer, and for other uses, with a great saving of fuel.”30 Travelling from the very birthplace of the Zwick’s Frommer’s wood-saving art, and having rubbed shoulders with the members of the consortium there, it would have to be an extraordinary coincidence if Aconcio was not acting on their behalf.

But the invention failed to take root yet again, as his petition was ignored. Aconcio had plenty of work cut out for himself already. The English paid him a generous salary of £60 a year for his services in modernising their fortifications, and it sounds like his water-raising machinery, which may actually have been his invention — a strikingly similar “Jacomo of Trento” had been named in a Venetian patent for such a device in 1545 — was applied to draining English marshlands.31 He wouldn’t have had much time left over to devote to further lobbying on the consortium’s behalf.

But despite Aconcio’s distractions, the holzersparungs kunst was too good an idea to wait a long time. In the summer of 1562, an English diplomat at Antwerp in the Low Countries, George Gilpin, wrote to the queen’s secretary of state, William Cecil, to update him on the petition by a consortium led by “Peter Stowghbergen”, sometimes spelled Stowghberghen, Stoughberken or Stochberghen — I haven’t yet been able to work out the true spelling — who were asking for a ten-year patent “for making of ovens or furnaces for brewers, dyers, and others, saving at least a third part of the fuel” — the exact same saving, yet again, as the Frommer-Zwick holzersparungs kunst.32

We have only the barest of hints about Stowghberghen’s background, which is that Gilpin mentioned he had been in Liège in the summer of 1562, “for the visitation of certain mines there” — presumably its coal mines. But Stowghberghen’s full offer, sent in October 1562, was rather charming. He promised to install a couple of his furnaces in English breweries at his own cost, to serve as a trial, and if successful would then charge an installation fee of £1 for every additional furnace, along with “meat and drink during the time the furnace is a-making, which shall not be above three or four days at the most”. Otherwise, the only payment he would ask would be a year’s worth of the cost of fuel that his invention saved, along with a rather boozy rent: “during six years, three barrels of the best beer a year.” As an afterthought, he decided that dyers and others who might need his furnace could give him “some like gratuity”. He also included various testimonials — from brewers and dyers in Antwerp, Ghent, Mechelen, Machelen near Brussels, and even the brewery of the Franciscan Friars at Leuven — showing just how widely the German wood-saving art had already been adopted.33

Perhaps because of Johannes Herdegen’s false start, Gilpin advised Cecil to include a condition in the patent that it would only be valid if Stowghberghen would come to England within a certain period of time. Despite at first suggesting a year, however, by the time the patent was actually issued in February 1563, to both Gilpin and Stowghberghen, the deadline was set at just two months.

But although Gilpin did send a technician to England “to make the proof”, presumably meeting the deadline, almost two years later in October 1564 he was writing to Cecil again to explain why he had still not made a “full trial”. The main thing to blame, he said, was “the great plague which reigned in England” in the latter half of 1563, which had killed about a quarter of all Londoners.34 This could well have made any foreign technicians reluctant to make the trip to London, and Stowghberghen especially so — when Gilpin first wrote about him, it was to report that he had only just recovered from being “dangerously sick”.

But the main purpose of Gilpin’s letter was to reassure Cecil that the project was still going ahead. Stowghberghen had, he noted, sold his share in the English patent, with the new investor promising “both offer and put in good sureties for the perfection of the work”. This was Godert von Bocholt, the lord of Wachtendonk, Pesch, and Grevenbroich, a diplomat and cavalry officer, who was the trusty and experienced lieutenant to William the Silent, the Prince of Orange, the Habsburg emperor’s commander in the Netherlands. Originally from the duchy of Gelderland, von Bocholt had once served England as a mercenary, having captained over 500 lancers and mounted arquebusiers in the 1540s for Henry VIII (for which he was still owed a lot of money, and which he was never to get back).35 With von Bocholt presumably providing the necessary funds, Gilpin was now preparing to send the same technician again as before, along with, most importantly, “another who pretends to be of more knowledge and cunning in those devices than the first”.

This new workman was, I suspect, someone peddling a competing holzersparungs kunst. Long before Zwick or Frommer had arrived on the scene, another consortium led by a Conrad von Gittelt had been promoting a wood-saving invention specifically for brewing — and which also claimed to save about a third of the fuel. Von Gittelt, apparently acting on behalf of an inventor named Sebastian Bräutigam, had managed to get a monopoly covering the kingdom of Bohemia in 1550, the whole Holy Roman Empire in 1551, and the electorate of Saxony in 1552.36

What precisely the Bräutigam invention involved, or how it differed from the Zwick-Frommer invention, I’m not yet sure. Frustratingly, I’ve not yet been able to confirm even the basic details about the names and dates, let alone to track down more. There’s even another fuel-saving invention I’ve seen mentioned from around the same time, associated with the name Götze, but the details seem to line up so exactly with the von Gittelt patents that I suspect they’re actually one and the same. But because anything written in German is so extraordinarily difficult to access — this has easily been my most expensive and time-consuming post to research by far — I can only hope that someone in Germany will read this and decide to devote some of their time to helping me flesh out the story. (Please do get in touch if this might be you!)

Although I’m reasonably certain that Aconcio’s petition was on behalf of the Frommer-Zwick consortium, given the strong Strasbourg Protestant connection, it’s possible of course that Herdegen’s earlier 1557 patent was actually on behalf of the Bräutigam consortium. Or even that he wasn’t acting as an official agent at all, and simply attempted to pirate the invention in England for his own gain. But in the case of Gilpin we at least have some stronger evidence. When the invention finally arrived on 20th April 1565, the mayor of London and a couple of other city worthies sent the government the testimonies of two brewers who had tried the furnaces, which were installed by a German they called “Sebastian Brydigonne” — seemingly none other than Bräutigam himself.37

It was natural that the process should have been tried by brewers, because theirs was a large and profitable industry, their product second in importance only to the bread, and requiring stupendous amounts of fuel. The brewer’s very first task was to boil lots of water, skimming away any impurities, and then leaving it to cool in a vat until the point that the steam had dissipated enough to see their face in it again — what we now know to be approximately 65°C, or 149°F. Then the brewer added malt — grains that had been soaked, allowed to germinate, and then dried and milled — stirring it with the water into a mash, and then tried to keep it at that warmth for the next few hours. After that the brewer allowed the liquid — or wort — to cooled, straining it, and in the case of making ale then leaving it with some yeast to ferment. To the brewer of ale, Bräutigam’s invention would already have offered a major saving by reducing the amount of fuel needed by a third. But the invention was especially valuable for the brewer of beer, as the wort, after straining, then needed to be brought to a rolling boil for at least an hour or two, at which point they also added the hops. Only then could they leave it to ferment. London’s beer-brewers testified that Bräutigam had not only saved them a third of their wood fuel, but had taken two hours off the whole process, presumably in the time it took to bring the liquids to a boil.

The demonstration was thus a resounding success, and brewers had both the means and the need to adopt it. But what precisely happened next is still, unfortunately, impossible to disentangle. There are too many loose ends.

To complicate matters immediately, neither Gilpin nor von Bocholt were actually named in the testimonial, though I’m certain that they were behind the demonstration. Von Bocholt wrote to Cecil in mid-February 1565 to say that he was going to put the patent with Gilpin into execution,38 and there’s a memorandum by Gilpin dated to the same month of the demonstration that says he’s about to make a full trial imminently.39 Given Gilpin’s diplomatic duties tied him almost permanently to the Low Countries, and von Bocholt was based there too, they would have needed to rely on agents in England to manage the patent on their behalves. And so the testimonial from the mayor mentioned these agents instead, saying that he had been “credibly informed” of the invention by a Richard Pratt and a Cornelius de Vos — both names that raise an extraordinary number of loose ends.

De Vos was a Protestant from the Low Countries, but resident in London, whose business involved cutting and engraving gems, as well as being “a most cunning picture maker”, probably a portrait painter.40 De Vos had recently acquired a monopoly patent to mine alum and copperas, had recently bought a German mining expert’s patent for a technique to pump water out of mines, and was a shareholder in the nascent Company of Mines Royal, which used German expertise to find copper in Cumbria. A year later he was to be off to Scotland, where he installed salt-boiling pans at Newhaven on behalf of English investors, and where he searched for gold on Crawford Moor.

I haven’t yet been able to tie him directly to von Bocholt, but I did accidentally stumble across a curious other piece of evidence, which hints further at a link. In the late 1560s, von Bocholt’s friend and captain William of Orange spearheaded a largely Protestant uprising in the Low Countries against the Habsburg Spanish emperor Philip II — the revolt that was to eventually lead to the independence of the northern provinces, now known as the Netherlands. When England sided with the rebellious Dutch in 1569, Philip II ordered the arrest of English merchants in the Low Countries, and so Elizabeth I retaliated by arresting many Dutch merchants in England — a group that included Cornelius de Vos. But a few months later, when the rebels sent representatives to London, one of the delegates wrote to Cecil to explain that de Vos was in fact a loyal supporter of the Prince of Orange, much like von Bocholt. And the delegate who pleaded for him was none other than Jan de Jonghe, or Doctor Junius of Antwerp, the early 1560s patentee in the Low Countries of the holzersparungs kunst!41 If I were to hazard a guess, von Bocholt and de Jonghe were probably partners in the monopoly of the process in the Low Countries, in addition to the share of Gilpin’s patent that von Bocholt acquired to cover England.

Where things start to get really messy, however, is with the other named agent, Richard Pratt. I’ve been able to find next to nothing about him except that his name also pops up, simply as a merchant taylor of London, in a draft patent among Cecil’s papers for a 21-year monopoly on the “instruction, art and knowledge of some expert men (having skill)” to reduce the consumption of fuel in furnaces — the holzersparungs kunst again — but this time with his partner not being de Vos, but one Steven van Herwijck of Utrecht.42 Van Herwijck, just like de Vos, was a Protestant gem engraver and portrait artist. He’s best known as a portrait medallist, and probably a painter too.43 I think it’s likely that they were partners. In fact, de Vos’s career even hints at the existence of a broader circle of collaborating artists, as his partners in the search for gold in Scotland were the portrait painter Arnold van Bronckhorst and none other than the goldsmith Nicholas Hilliard, the most talented and famous English portrait miniaturist of the Elizabethan age.

But just as the plot starts to thicken, the available evidence throws an unexpected spanner into the pot. This is a petition in Cecil’s papers by a “Peter Jordayne” and associates to introduce various inventions into England. Along with a kind of rotisserie oven, a pump for mines, and improvements to baking ovens and brick kilns, the list is headed by furnaces for brewers and dyers to save — you guessed it — at least a third of the fuel.44 And the patent itself was to be in the name of yet another person, George Cobham, or Brooke. The younger brother of William Brooke, Baron Cobham, and the queen’s own second cousin, George Cobham was, like Gilpin, employed as some kind of diplomat or agent abroad. He’s named on just one other patent — for a the river-dredging machine invented by a Venetian merchant based in Antwerp — but other than that he left frustratingly little trace, and I’ve not been able to find any further details about Peter Jordayne at all.

The big problem with fitting the Jordayne-Cobham petition into any kind of narrative is that there’s no clue as to when it was written. Despite the petition being filed amongst various documents for 1575, Cobham was most certainly dead by 1571 because his widow remarried.

Although we have a similar problem with the Pratt-Herwijck draft patent being undated, we can at least narrow that one down. Van Herwijck seems to have come to England before, but at the end of March 1565 — just a month after von Bocholt wrote to Cecil, and just a month before the ovens were to be demonstrated in London — he was petitioning the city leaders of Antwerp to be excused certain municipal taxes so that he could leave town with his family for three years “because he had agreed to make certain works for the queen of England, which works he has already begun”.45 The request was rejected because he then refused to reveal any specifics or certification — a kind of paranoia typical of people dealing in inventions — but I suspect it’s a reference to the holzersparungs kunst, especially as his draft English patent wasn’t just for a monopoly on the technique itself, but would also have made van Herwijck a full English denizen, “in all things to be handled, reputed, holden, had and governed as our faithful liege subject born within this our realm of England.”

Unfortunately for van Herwijck, he wouldn’t have had much time to enjoy his new rights. Just over a year later, in August 1566, he had apparently become sick enough to make his will, and by March 1567 he was dead.46

Given this evidence, the Pratt-van Herwijck draft patent very probably dates to 1565, right after the successful demonstration by Bräutigam. But to thicken the plot yet again, to the point of becoming almost entirely indigestible, in that same year — just five months after the demonstration — the patent petition of Jacopo Aconcio from seven years earlier was suddenly granted too!

So what on earth was going on? What we’ve seen are the hints I’ve so far been able to track down, at least from the English sources. But until any more evidence turns up, most likely from archives abroad, I think we can at least piece together a likely chain of events.

One Patent to Rule them All

The key thing to note is that patents were not quite the same as today. Today, dozens or even hundreds of tiny tweaks to ovens will be patented every year, each of them outlined clearly and examined by specialised officials to see that they’re original and don’t overlap. The patented invention has to be specified with detailed descriptions and drawings, and the monopoly is over copying it exactly, with the courts ultimately deciding how much leeway to give. But in 1560s England, patent monopolies were much more broadly construed. Instead of letting hundreds of minor inventions compete in the market on their merits, potential competitors were instead forced to combine their efforts, so that there was typically only one patent per industry at any one time.

Patents were intended as the key tool to actually introduce a whole new industry or technique — as a tool of what we’d now call industrial policy — and so they restricted competition as far as was practicable to make an otherwise extremely risky venture attractive to investors. After all, introducing a new industry or process meant having to find sufficiently skilled foreign technicians, persuading them to move to England, transporting, feeding, and lodging them when they arrived, and persuading them to stick around and actually put their skills to good use — all before the costs of securing materials, premises, and erecting unfamiliar machinery. But granting such a strong monopoly usually came with conditions, such as having to introduce the new technique within a certain amount of time, meeting certain production quotas, selling at particular prices, teaching the technique to native English workers, or paying a high annual rent to the Crown (the theory being that this would replace the revenues lost by a new industry replacing imports, on which customs duties were charged).

When we see multiple patents granted for the same industry over just a handful of years, this typically meant that the original patentees had failed to keep to the terms of their patent, had gone bust, or had even simply died, requiring a new one to be reissued to new entrepreneurs. It’s what we see with many of the better-documented patents — for making salt, glass, sulphur, copper, and mine-draining — where what would otherwise appear to be a spate of new inventions is actually, as we know from their petitions and letters, just the exact same monopoly having to be re-issued to a new group of investors or entrepreneurs.

So with that in mind, what I suspect happened with the English patent for the holzersparungs kunst was the following:

Shortly after the successful demonstration of the furnace by Bräutigam in April 1565, Gilpin and his new partner, the mercenary commander von Bocholt, decided it would be a good idea to get a new patent in the names of their agents, who would then take over the whole project and most likely pay them some kind of dividends for their trouble. There were several good reasons for this. Peter Stowghberghen, who had sold his share to von Bocholt, was still named on the old patent, and Gilpin’s career was preventing him from actually going to England to oversee its execution. Most importantly of all, however, given the competing versions of the holzersparungs kunst in the rest of Europe, the original patent had neglected to stipulate what the punishment would be for infringement.

In a telling letter by Gilpin to Cecil in 1564, when excusing his delays, he worried how “we have no refuge but to your Honour, whose assistance, if need require, we must humbly desire, as well against such as should attempt to counterfeit our work during the time of our placard [patent] as other hinderers of the same, for which sort of men no penalty is ordained by special words in the privilege”.47 So I think they must have tried to get their patent renewed and strengthened in the names of their agents, Richard Pratt, Cornelius de Vos, and most likely Steven van Herwijck too, who as we’ve seen was already preparing his departure to England just a month before Bräutigam’s demonstration. The reason van Herwijck isn’t mentioned in the mayor’s testimonial is most likely because he wasn’t an established enough figure in London to be a credible informer, whereas de Vos had been in the city for years, and was already naturalised, even marrying an English woman — he’s described in his 1564 alum patent as the queen’s “liege-made subject”.48

But as de Vos was busy with so many other projects, and was soon off to Scotland in any case to search for gold, I suspect that his role as von Bocholt’s agent was only ever intended to be temporary, until his fellow gem engraver and portraitist Steven van Herwijck had arrived. Once that occurred, van Herwijck and Pratt then applied for the new and stronger patent, which this time did not fail to include harsh punishments for infringers: a whole year of imprisonment without bail, along with the forfeiture of an eye-watering £100 for every offence.

In the process of applying for this new patent, however, I suspect that Aconcio got wind of this and raised a fuss, pointing out to Cecil that he had applied for a monopoly on the fuel-saving furnace long before even Gilpin, and perhaps also that the Frommer-Zwick invention he had tried to patent was slightly different to the one being peddled by Bräutigam. One interesting feature of Aconcio’s patent is that it explicitly mentions how “the licence shall not derogate from any grant heretofore made to any person” —something you only ever see in the tiny handful of cases where more than one patent was granted per industry, and which I suspect was a direct reference to the Gilpin-Stowghberghen patent. But the experiment in allowing competing patents was to be very short-lived, as just a year later Aconcio was dead.

It doesn’t seem as though the Pratt and van Herwijck draft patent was actually granted. It’s not copied into the patent rolls, which is where you’d expect to find it if it had been, and after his death his family were recorded as not being denizens. But then Aconcio very probably delayed it when getting his own patent, and had died the following year just as van Herwijck himself became fatally ill. Perhaps by the time the delays were dealt with, it was already too late. Or perhaps Cecil thought that Gilpin’s original patent with Peter Stowghberghen was sufficient to protect the partnership, and that with enough political protection from himself, a new one would not need to be issued after all. Or perhaps, as was very common at the time, the partners recognised that Aconcio’s patent was most likely to be granted based on priority, dropped their own attempt to lobby for a patent of their own, and then bought a licence from Aconcio only for him to immediately die. Whatever truly happened, it would have involved considerable expense, and may well have curtailed the effort to spread the invention.

As for George Cobham’s undated petition to patent the invention on behalf of a Peter Jordayne, however, we can only guess. It’s possible that Gilpin’s long delays in putting his patent into practice opened an opportunity for rivals to step into the breach, and to attempt to acquire the monopoly for themselves. Perhaps Jordayne’s company were the counterfeiters and hinderers that Gilpin referred to when he anxiously wrote to Cecil to ask for his support, and that’s why the petition went nowhere. Perhaps Jordayne’s company were the official agents of some other, slightly later German consortium with a holzersparungs kunst of their own, or perhaps they weren’t officially acting on anyone’s behalf at all, and were simply trying to pirate the invention in England for themselves. Or perhaps they petitioned later, once Aconcio and van Herwijck had died, and with the invention’s adoption having therefore stalled, only to find that Gilpin’s patent was still in force to block them. Ultimately, until further evidence turns up from abroad, we may never know for sure. But what is clear is that between Herdegen, Aconcio, Gilpin, Stowghberghen, von Bocholt, Bräutigam, de Vos, Pratt, van Herwijck, Cobham, and Jordayne, there was a huge amount of effort in trying to bring the invention to England, which in terms of saving wood fuel had an obvious value to the country’s major industries like brewing.

Which brings us, finally, to the invention’s ultimate success.

A Royal Brew-haha

While all this jostling for the English monopoly was going on, back in Strasbourg the art of wood-saving was developing further. Although the Frommer-Zwick invention saved at least a third of the fuel, it took some effort and skill to get it to work well. With only a small chamber in which to burn the wood, it required frequent refuelling along with plenty of additional chopping and splitting of the wood into smaller pieces, careful placement of the chopped wood on the grate in the furnace chamber, and lots of fiddling about with allowing in more air for the fire and releasing the smoke — inconveniences, ultimately, that brought the invention into disrepute in Germany, as when forced to choose between saving costly wood or even costlier labour, saving on labour won out.49

In 1563, however, a Strasbourg gunsmith, one Michael Kogmann, sometimes spelled Khagman or Cogman,50 had invented a way to eliminate these inconveniences while still saving a third of the fuel, and once the Zwick-Frommer monopoly drew to an end, in 1571 he persuaded the city authorities to back him and his partners — his brother Heinrich, a soapmaker and tavernkeeper, and his fellow gunsmith Jeremias Neuner — for a patent monopoly of their own. Neuner and the Kogmanns got a patent for the whole Holy Roman Empire in 1572, demonstrating their improvements to acclaim in Vienna, Cologne, Leipzig, Mainz, Kassel, Mansfeld, Eisleben, Wetzlar, at the Hallstadt salt pans, and in Moravia, in modern-day Czechia. Many localised patent monopolies followed, and in 1575 the Imperial patent was renewed and extended to cover further potential applications.

But most importantly, in 1574 the invention made its way to England. Finding a merchant in Strasbourg who had dealings in England — someone to make the necessary introductions — Neuner himself made the trip. He and the merchant, one Georg Zolcher, soon got a patent monopoly. Gilpin’s ten-year term, if still in force, would have expired just the previous year. But the new patent gave them a monopoly for only five years — an unusually short term, which perhaps reflected Cecil seeing it as only a minor improvement, rather than a major new technological feat.

Either way, neither Cecil nor the inventors realised the value of what they had achieved. When Neuner and Zolcher applied for their patent in England they mentioned industrial applications like brewing and dyeing, seemingly only to cover all their bases, and instead focused on on how they would save fuel “chiefly in the great halls of noblemen”, as well as in hearths used for cooking, all “without any exceptional trouble in changing flues”. And their focus was entirely on saving fuel in the form of wood.

But the evidence we have of its actual application — one of those most precious of things in the history of sixteenth-century invention — gives the first hint at the invention’s extraordinary effects. It consists of a brief minute in the records of the Privy Council, the central organ of England’s government, from four years after the patent, in which the mayor of London was ordered to “call before him such brewers and others of that City as put in practice the device of the two strangers [that is, foreigners] for the sparing of wood” — an unequivocal reference to Neuner and Zolcher’s patent, which shows that the wood-saving art had once again proving most popular among London’s brewers.51

That alone is something, and in the printed calendars of the Privy Council records, that’s pretty much where it ends. But in one of those immensely satisfying cases where all my over-the-top double-checking immediately paid off, it turns out that in the manuscript itself there’s a line crossed out. And having spent the last few months teaching myself to read scrawly sixteenth-century “secretary hand” so that I can read all the original manuscripts for just such an occasion, I’m fairly sure that the crossed out line is an order to the mayor of London “to inhibit them the use thereof” — that is, to stop the use of the Kogmann-Neuner invention in its tracks.

Why did the authorities try to stop its use? Or, if the line was crossed it out because they decided to give the brewers a chance to respond, why would it have been cause for complaint?

The answer was that by adopting the holzersparungs kunst, the brewers had discovered a way to save far more than a third of the cost of their fuel. They had discovered that instead of burning wood, they could now use much stinkier, but much cheaper coal. The original inventions of Frommer, Zwick and their rivals had introduced the principle of heating things up via the flue, achieving their fuel saving by separating the smoke of the fire from whatever was being heated — something that would immediately have allowed coal to be burned in brewing instead of wood, by no longer risking the thick, heavy coal soot tarnishing the brew. And I suspect that after Bräutigam’s successful demonstration in 1565 it did occur to brewers to try. Indeed, many of the supposed problems with their invention as used in the rest of Europe, largely to do with not having enough space in the furnace chamber for the wood, would have been mitigated by using coal because it’s so much denser a fuel by volume — it would have taken up roughly half the space in the furnace chamber.

Whether this was realised in the late 1560s, prior to Neuner’s patent, is so far impossible to say. I’ve not yet seen any solid evidence of it beyond some of the patents covering “other fuels”, which I think was just as a precaution. The closest thing to it is an estimate of brewing costs — in which the fuel is unequivocally described as being “coals” rather than wood — labelled as being from “about October 1574”, or just a couple of months after Neuner’s patent, though such labels are often unreliable, so should be taken with a pinch of salt.52

What we know for sure, however, is that after Neuner introduced Michael Kogmann’s improvements, the use of coal by brewers had soon become universal in London, and become major source of complaint. Less than a year after the Privy Council’s letter to admonish brewers using the invention, in January 1579 the offensive stench of coal smoke had apparently become so common that it was too much for the queen to bear, the Privy Council ordering London’s brewers to no longer “burn any more sea coal during the Queen’s Majesty’s abiding at Westminster”. When this order was ignored — switching back to wood, especially on short notice, would have been extremely costly — fifteen brewers and a dyer were even hauled off to jail. The brewers protested, pointing out the vast amounts of wood that the switch to coal had saved, but a month later they had reached an agreement to no longer burn coal on specified days when the queen was in town, so long as they were given advance warning.53

But seven years on, the sulphurous stink of London’s breweries had become so great that it put the queen off from visiting the city at all if she could avoid it. Apparently assaulting her senses whenever her barge wended its way down the Thames, in early 1586 the authorities ordered the brewers to cease their burning of coal along the river. This time, however, the brewers responded in a way that reveals just far the use of the wood-saving art had spread. The city’s dyers and hatmakers, they said, as well as the brewers, had now all “long since altered their furnaces and fire places and turned the same to the use and burning of sea coal.” Dutifully, they offered to switch two or three of the breweries nearest to the Palace of Westminster back to burning wood, though pointed out that even just this would have a huge effect on the city’s fuel supplies, consuming a whopping 2,000 loads of wood per year.54

Nothing more is heard of the matter in the state documents, so presumably the queen accepted their sacrifice. But it’s also possible that she simply gave up: given the huge cost savings to such a vital industry, there was no holding coal’s conquest back. By the late 1570s, given the sheer quantities of beer and ale being produced in the city amounted to some 400,000 barrels a year, the breweries alone would have required a near doubling of the city’s coal total consumption, adding some 10,000 tons of coal per year to the 10-15,000 tons consumed by the city’s blacksmiths and lime-burners,55 not to mention the amounts consumed by the dyers, hatmakers, soapmakers, and others who could most readily adopt the holzersparungs kunst.

And, crucially, with that doubling of demand for coal from Newcastle, the mines had to be dug deeper, soon striking coals that were much larger and less crumbly, with less sulphur than before — coals that, with the grates and chimneys that had already been in use elsewhere for centuries, were much more easily burned in the homes of Londoners too. Indeed, based on the experience of the century and a half that followed, it was believed to be a rule that the deeper the mine, the larger coals — a myth only busted when the adoption of the steam engine allowed miners to drain the mines of their water, reaching far deeper than ever before.56

By the 1590s, London’s consumption had expanded by eight- or even tenfold over what it had been in 1560, with the vast majority now burned in people’s homes.57 But what I believe the evidence shows us is that London’s voracious appetite for coal did not start in the hearths of its homes. Instead, thanks to some enterprising Germans whose names had largely been forgotten, it was instead first whet by ale and beer.

Thank you for reading. If you’d like to support my research, you can upgrade to a paid subscription here:

Norman Scarfe, ed., A Frenchman’s Year in Suffolk: French Impressions of Suffolk Life in 1784 (The Boydell Press, 1995), pp.5, 51, 137; Norman Scarfe, Innocent Espionage: The La Rochefoucauld Brothers’ Tour of England in 1785, First Edition (The Boydell Press, 1995), p.24

Thomas Almeroth-Williams, City of Beasts: How Animals Shaped Georgian London (Manchester University Press, 2019)

William Harrison, The firste volume of the chronicles of England, Scotlande, and Irelande (1577), p.85; for some of the best descriptions of coal-burning technology in the home, see also Ruth Goodman, The Domestic Revolution (Michael O’Mara Books, 2020)

‘Pehr Kalm’, in The Linnaeus Apostles: Global Science and Adventure Vol III, Book I (IK Foundation & Co, 2008), p.116

Hugh Plat, A nevv, cheape and delicate fire of cole-balles wherein seacole is by the mixture of other combustible bodies, both sweetened and multiplied (1603)

Scarfe (1995a), p.4

Robert C. Allen, The British Industrial Revolution in Global Perspective, 1st ed. (Cambridge University Press, 2009), p.95

John Hatcher, The History of the British Coal Industry: Volume 1: Before 1700: Towards the Age of Coal (Oxford University Press, 1993), pp.27, 412

'Venice: May 1551', in Calendar of State Papers Relating To English Affairs in the Archives of Venice, Volume 5, 1534-1554, ed. Rawdon Brown (1873), pp.338-362, accessed via British History Online

Stephen [Estienne] Perlin, “A Description of England and Scotland”, in The Antiquarian Repertory, Vol I (1775), p.235

P. S. Donaldson, ‘II George Rainsford’s “Ritratto d’Ingliterra” (1556)’, Camden Fourth Series 22 (July 1979), p.90

Abraham Ortelius, Theatrum orbis terrarum, or Theatre of the Whole World (John Norton, [1570] 1606), in ‘Of the Orkeny Iles, West Iles, Man, &c’; also see the various mentions of coal in Harrison

J. A. Cramer ed. The Second Book of the Travels of Nicander Nucius, of Corcyra (Camden Society, 1841), p.p.xviii-xx

Harrison, p.91

Ibid., p.78

Luis de Granada, The Singularities of London, 1578: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana MS Reg. Lat. 672: Number 175, ed. Ian W. Archer, Derek Keene, and Emma Pauncefoot, New Edition (London Topographical Society, 2014); Lupold von Wedel, in Queen Elizabeth and some Foreigners (John Lane and Bodley Head, 1928), pp.313-46

Quoted and translated from John Caius in 1555 in Robert L. Galloway, Annals of Coal Mining and the Coal Trade (The Colliery Guardian Company Ltd, 1898), p.109

'Venice: August 1554, 16-20', in Calendar of State Papers Relating To English Affairs in the Archives of Venice, Volume 5, 1534-1554, ed. Rawdon Brown (London, 1873), pp.531-567, via British History Online

William M. Cavert, ‘Industrial Coal Consumption in Early Modern London’, Urban History 44, no. 3 (August 2017), p.427

“Thomas Barnaby to Sir William Cecil, proposing methods of distressing the French, 1552”, in Henry Ellis ed. Original Letters, Illustrative of English History, Vol. II (Harding and Lepard: 1827), p.199

Harrison, p.115; see also TNA SP 12/105, “Discourse on the establishing a staple at Newcastle for coals, and for tin and lead in other places”, dated August 24 1575, which notes how “coals have been known beyond the seas as well in the Low Countries where they have no coals to serve smiths but such as with great charges are brought out of the lands of Liège, as well in Picardy, Normandy, Brittany and other places of France that for the smiths’ occupying they have no coals to be brought unto them so good cheap as Newcastle coals, which has been manifested and proved in long while for the great number of those countries’ ships [that] usually every year in summertime repair to Newcastle for coals”.

Hatcher, p.40

Graham Hollister-Short, ‘The Other Side of the Coin: Wood Transport Systems in Pre-Industrial Europe’, in History of Technology, ed. Graham Hollister-Short and Frank James, vol. 16 (Bloomsbury, 1994), pp.80-1

Unless otherwise stated, details of the consortium are from Hans Rudolf Lavater, “Der Bieler Dekan Jakob Funcklin und die Anfänge der „Holzsparkunst“ (1555-1576)”, in Ulrich Gäbler, Martin Sallmann & Hans Schneider, éd., Schweizer Kirchengeschichte - neu reflektiert. Festschrift für Rudolf Dellsperger zum 65. Geburtstag (Basler & Berner Studien zur historischen & systematischen Theologie, 73, 2011), pp.63-145

G. Doorman, Patents for inventions in the Netherlands during the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries: with notes on the historical development of technics (1942)

I came across this completely by chance. It’s listed in a couple of sourcebooks, but seemingly has never been written about. It doesn’t appear in any of the lists of early patents for inventions, and I don’t see it mentioned in any books or articles on the subject.

Calendar of the Patent Rolls: Philip and Mary, Vol. IV, AD 1557-1558, pp.132-3

Jack Williams, Robert Recorde: Tudor Polymath, Expositor and Practitioner of Computation (Springer Science & Business Media, 2011) has all sorts of details about the Clonmines project

For a recent summary see John S. Moore, ‘Demographic Dimensions of the Mid-Tudor Crisis’, The Sixteenth Century Journal 41, no. 4 (2010), pp.1039–63. But there’s actually even more evidence been piling up since in local studies.

Jr. Lynn White, ‘Jacopo Aconcio as an Engineer’, The American Historical Review 72, no. 2 (1967), pp.425–44

Jeremy Phillips, ‘The English Patent as a Reward for Invention: The Importation of an Idea’, The Journal of Legal History 3, no. 1 (1 May 1982), p.76

SP 70/40 f.92

SP 70/43 ff.129-130

SP 70/74 f.198

For many details about von Bocholt, see Piet Dekker, Godert van Bocholt enige heer, grootgrondbezitter en zoutzieder van de Zijpe (Pirola, 1998). But even this very thick tome seems to miss lots of details about his life, particularly to do with his investments in inventions.

Hansjoerg Pohlmann, ‘The Inventor’s Right in Early German Law’, Journal of the Patent Office Society 43, no. 2 (1961), pp.121–39, particularly footnote 68.

SP 12/36 f.85

SP 70/82 f.88 - this is labelled by the calenderer as 1566, assuming that the year was being counted from Annunciation Day on 25th March instead of from 1st January. Although English writers could go back and forth on this, most other European countries had made the shift by then to a January start, and the letter is clearly dated “February 1565” by von Bocholt himself. And it’s also the only date that actually makes sense given the context. Incidentally, this letter has never been attributed to von Bocholt before, being mislabelled as from “M. Bochet”. But it very clearly states that it is from the lord of Grevenbroich.

SP 12/36 f.102

Stephen Atkinson, The Discoverie and Historie of Gold Mynes in Scotland, 1619 (Bannatyne Club, 1825), p.33

Cotton Galba C/III f.148

Lansdowne Vol/105, “A draught of the Queen's grant to Rich. Pratt and Steph. Van Herwick for new invented furnaces”

See, for example, Bendor Grosvenor, ‘The Identity of “the Famous Paynter Steven”: Not Steven van Der Meulen but Steven van Herwijck’, The British Art Journal 9, no. 3 (2009), pp.12–17. There is lots written about him as an artist, but not his role as an inventor. The only person to have ever written about him in this capacity before, but without making the connection to the famous medallist, is Deborah E. Harkness, The Jewel House: Elizabethan London and the Scientific Revolution (Yale University Press, 2007).

SP 12/106, f.24

Victor Tourneur, ‘Steven Van Herwijck. Médailleur Anversois (1557-65)’, The Numismatic Chronicle and Journal of the Royal Numismatic Society 2 (1922), pp.100-4.

See Grosvenor for this discovery.

SP 70/74 f.198

CPR, Elizabeth I Vol III, 1563-66, p.119

See Lavater for details, as well as some key facts about the Kogelmanns and Neuner. Lavater calls Neuner a fortifications engineer, which he was later on from about 1579 onwards, but he was usually described as a gunmaker.

For the alternative spellings see their own advertisement of the imperial patent here, and a testimonial written for them by the manager of the Hallstadt saltworks at SP 70/147/2 f.411.

PC 2/12 f.169

SP 12/98 f.161 - the alternative, older numbering is f.37

For the fullest and most detailed account of the 1579 and 1586 controversies, which corrects some errors found in other works, see William M. Cavert, The Smoke of London: Energy and Environment in the Early Modern City (Cambridge University Press, 2016), pp.45-8

Ibid., and SP 12/127 f.117. Cavert notes that this document has been mis-dated to 1578, and is instead the response of the brewers to the orders of 1586.

Cavert 2017, p.430, and especially 436. I think Cavert’s estimate of over 10,000 tons is far likelier than that of 8,000, though I’d hesitate to put that figure for 1574, and rather for 1579. Hence why I’ve written “late 1570s” to fudge the difference, and because it will only ever be a rough figure in any case.

J. U. Nef, The Rise of the British Coal Industry, Vol. 1 (London: George Routledge and Sons, 1932), p.114

Cavert 2017

I don't understand my own cursive. Secretary hand from the 1500's looks greek to me.

People underestimate how man's quest for beer has changed the world.

Amazing work.

Hi Anton.

Phew! The technology of and market for cast iron grates firebacks and other aspects of making hearths suitable for burning high CV coal is a subject worthy of further work in the archives.

I'm so glad I stuck to the eighteen century.