Age of Invention: How to be a Public Historian

Writing for a public audience is a double-edged sword. It’s all very well to want to put your work out there and reach as wide an audience as possible – and even if it’s not something you really yearn for, it’s still heavily encouraged and incentivised throughout academia. But it comes with significant risks, and those only grow and multiply as you reach a wider and wider audience.

Most people have no conception of what it might be like to reach a truly massive audience. A few years ago the self-help guru Tim Ferriss wrote an eye-opening piece on what it’s like to be even only somewhat famous. There are certainly upsides. You might make new friends, be able to substantially aid the causes you’re passionate about, and perhaps even make some money.

But as Ferriss notes, it’s a Faustian bargain. Just through sheer numbers alone, if your work reaches an audience the size of a city, or perhaps even a small country, then it will inevitably reach a lot of people who are simply mad, bad or sad. Even if you’ve said nothing that could reasonably be construed as controversial, you might receive threats and have insults hurled at you. You’ll receive all the more if you have. And even the most anodyne or obscure things you have said will reach people who want it to be either completely false or unquestionably true. All just because it will allow them to score some cheap point over some other people they loathe. The wider the audience your work reaches, the more this will happen.

Along with those risks, however, if you try to reach a wide public audience then you also have a responsibility – because the things you put out there will be used in ways you may never have anticipated and which you simply cannot control. To give a personal example, a few years ago I wrote a couple of pieces on whether the Ottoman Empire really banned the printing press, in which I raised the speculative possibility that what had been called a “ban” by European observers may actually have been an excuse used by Ottoman officials to block specifically foreign, Christian propaganda. Now, I took great pains to show exactly what scanty evidence I was drawing on to infer that story and signalled throughout that it was really very speculative. But I occasionally see it shared on social media by Turkish nationalists as definitive proof of what happened, and serving as ammunition against people they feel are insulting their heritage by merely saying that the Ottoman Empire had restricted the printing press. And that’s despite even opening the piece by noting how the politicisation of the history of the printing press in the Ottoman Empire – on all sides, no matter how well-meaning – has got in the way of actually working out the truth. (Hate-mail incoming in 3.. 2..)

Given the unpredictable ways in which historical work gets used and abused as it reaches a wider audience, it does however demand caution. If you make a speculative case, it should be very clearly labelled as speculative. And if you present speculation as fact, then the wider the audience this reaches, the more you can expect this to be called out. Because we all like to know what’s true. Given the way information is used or abused, for better or for worse, the one thing that unites the good actors and the bad is that they like to be dealing with information they’re confident is sound.

One thing I’ve noticed as my own audience has grown – to over 26,000 people now, far in excess of what I ever expected when I started this newsletter just over four years ago – is that there is no surer way to provoke a reaction, ranging from the painfully polite correction right down to hostile name-calling, than to make an actual mistake, even if it’s entirely innocent. There seems to be a fairly universal human urge to correct what is incorrect, each in our own way, and bring our own expertise to bear, whether we notice a thesis-shattering counterproof or even just a mere spelling mistake.

This is downright terrifying. Long-time readers might have noticed that nowadays I tend to publish much longer but also less frequent posts than I did some years ago. This is because as my audience has grown from the hundreds to the thousands and then to the tens of thousands, I feel a greater and greater sense of responsibility to not accidentally get something wrong. It’s embarrassing enough to tell a story that turns out to be wrong to a group of friends – we’ve all been there. But it’s excruciating when you’ve accidentally misinformed a group the size of a medium-sized town.

And yet, it’s also exciting. When you reach a large audience you inevitably also reach people who are better-informed or more specialised than you on a dizzying and even unpredictable range of topics – a large audience is also a wide audience. Even if I think I know a lot about early steam engines – and I think it’d be fair to say I know more than even the average historian of technology – with a wider audience it gets more and more likely that the things I write will come to the attention of people who know far more. It’s a simple, mathematical inevitability.

It’s not just inevitable. It’s to be actively sought, because it makes us better. One of my favourite things about what I do is that I have come to the attention of people who possess a vast and specialised expertise on a wide range of topics – and who will not hesitate to correct me when I’m wrong. I can’t help but experience a little trepidation when I see certain names pop up in my inbox or on social media – like John Kanefsky when I happen to mention steam engines, John Styles when I write about textiles, or Judy Stephenson when I mention labour practices, to name just a few. When such names pop up, even if I haven’t actually got anything wrong, I know I’m still about to be schooled. And that my work is about to be improved as a result. Reaching a wider audience and actively seeking correction disciplines me to check the information I put out into the world, or at the very least to express my uncertainty where it’s appropriate, and it makes it more likely that any misinformation I’ve already inadvertently put out there gets cleaned up.

The other day I got to meet another substack newsletter writer with an audience of a similar size to mine – the wonderfully curious Mike Sowden. One thing he did recently is ask his audience to leave a comment calling him an idiot, ideally explaining why – both a call for correction and a kind of icebreaking exercise so that, having already called him an idiot once, people will get in touch with him more often with their corrections in future. From what he tells me, it sounds like it’s been a roaring success, exposing him to the privilege, quite frankly, of his audience’s expertise. I’ll remind you again later, but when you’ve finished reading this to the end I’d like you to leave a comment: it may or may not be to correct something I’ve said here or elsewhere, but at the very least just call me an idiot.

Principles of Proportionality

Now, Mike and I are clearly gluttons for punishment. And in general calling people idiots is unlikely to result in misinformation getting corrected by the people responsible for it. Even if it’s thoroughly deserved. It certainly is in Mike’s case. But the way we try to correct misinformation, intentional or otherwise, has to be proportional.

This brings me to a case I first wrote about in July, and which I returned to in August, when new evidence had come to light. You’ll have to forgive me for bringing it up for a third time, and I’d even resolved after the second time that that would be that. In the months that followed I’d avoided any further mention of the matter on social media, and I’d scrupulously avoided even “liking” any posts about it, as I knew that might propel it into people’s timelines again. I felt I had already acted proportionately in trying to correct some misinformation, and that taking it any further would be pushing it. So I’m hoping this will be the very last time I ever have to mention it in public ever again. You’ll see why.

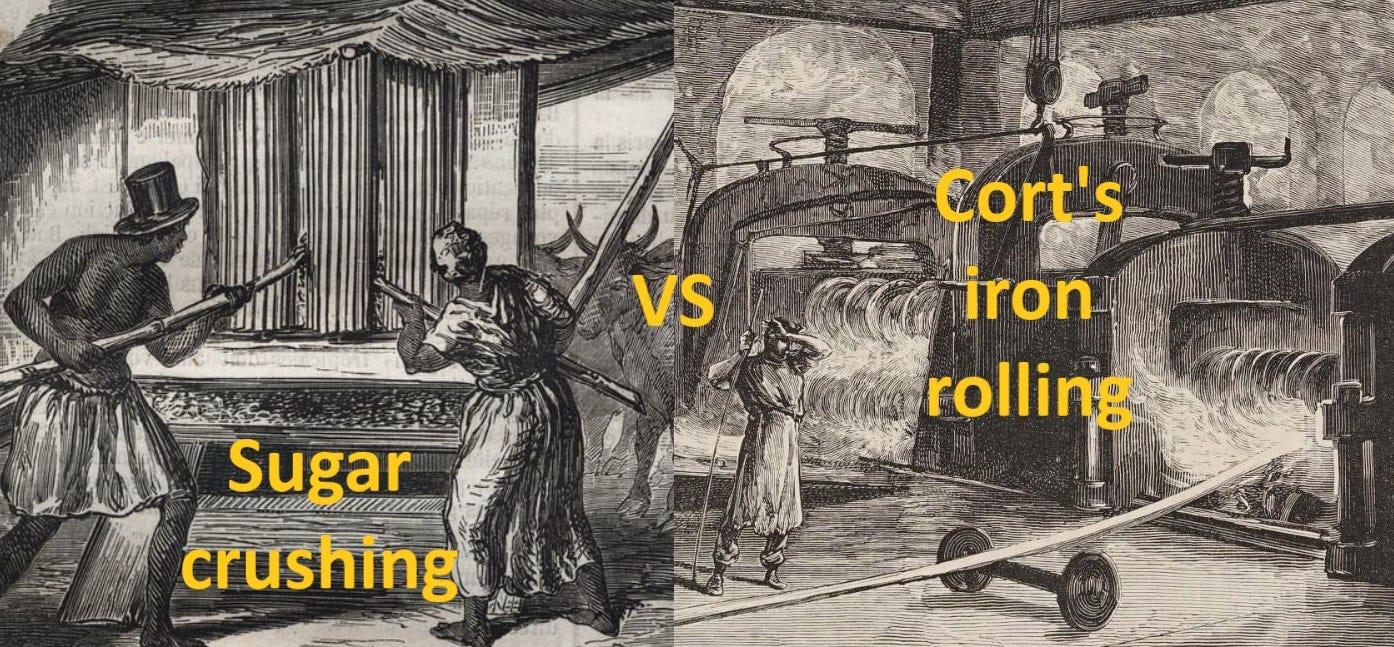

The case involves a paper by Jenny Bulstrode published in June in the journal History & Technology. As a quick recap, it claimed the following: that the inventor Henry Cort had stolen his famous 1783 iron-rolling process from an ironworks called Reeder’s Pen in Jamaica, where it had been developed by 76 black metallurgists by passing bundled scrap iron through grooved sugar rollers. The paper then claimed that Henry Cort heard of the process via a cousin named John Cort who had been in Jamaica, and that Reeder’s mill was destroyed and its machines dismantled and taken to Portsmouth where Henry Cort could use them. It insinuated, though without saying so directly, that Cort may have used his connections in the Admiralty to achieve this destruction and theft (something that the author then claimed explicitly in the media, specifically on a podcast called The Context of White Supremacy).

It was very widely reported in the press – in The Guardian, Mirror, New Scientist, on NPR, and in heaps of local newspapers and more niche sites. On social media it went viral, with thousands of people reading and praising it. And I think it’s fair to assume that this attention was actively courted. Someone made the decision for the paper to be made open-access, and thus free for all to read rather than behind the usual academic journal paywall, and the paper was heavily promoted by the journal’s publisher Taylor & Francis as well as by the writer’s department of Science and Technology Studies at UCL. Within days there were local politicians calling for Cort’s name to be expunged from the names of streets and public buildings, and the Wikipedia entries associated with Cort and his innovations were heavily updated in light of its conclusions. After all, History & Technology, as a double-blind peer-reviewed journal, has all the hallmarks of a trustworthy source.

But as I said before, pursuing a larger and wider audience for one’s work is a double-edged sword, coming with significant risks and responsibilities.

You can be sure that it’s going to reach a lot of people who will attempt to use your work for their own ends. There will be a great many people who will want it to be right, because it is a compelling illustration of the neglected historical achievements of black people and of the injustices of colonialism and slavery. Indeed the author herself indulged in this, portraying it in the media as important evidence of the need for reparations. But there will also be a great many people who want it to be wrong, perhaps because they wish to downplay historical injustices or the achievements of black people, or even just so that any criticism can show that the political activists they disagree with are more generally untrustworthy. “Woke gone mad”, etc.

Yet for these political arguments whether it’s actually true or not is really neither here nor there. It’s not as though we don’t already have countless cases of the injustices of colonialism and slavery or examples of the achievements of black people. It’s not as though showing someone was wrong about a single, hyper-specific case study does anything at all to invalidate much broader political arguments. It’d be enormously egotistical of historians to pretend otherwise, as though real justice can only be pursued or achieved because of their own research.

The philosopher Liam Kofi Bright skewered it all perfectly in a single tweet:

Huge debate going on among historians right now about whether some black metallurgists did something with rollers (?) that made steel more... steely... and then had that nicked by some Brit. The fate of equality rests on this, following matters closely.

Quite. And if you do think that the fate of equality hinges on whether a man who died 223 years ago copied and took credit for a very specific ironmaking technique that until a few months ago only a handful of nerds like me had ever even heard of, then I’d prescribe a complete political and current affairs detox. I’m qualified to prescribe this as a doctor with a real PhD, rather than a mere physician: throw away your smartphone, cancel your broadband, and keep yourself at least five miles distant from the nearest population centre for at least a year. The full works.

And apart from those who want you to be wrong or right, you’re also going to come to the attention of people who know a thing or two about the things you’ve discussed – those terrifying people with deep expertise, and even just the more generalist but informed idiots like me. I read the paper the day it was published, but I didn’t write anything about it until after a number of people began to either email me or ask me on social media about it. As I write regularly about inventors of the Industrial Revolution, some people naturally looked to me for my relatively informed opinion.

And I considered the narrative about Henry Cort to be wholly unsubstantiated, for the reasons I set out back then. I judged it to be misinformation, and misinformation that was spreading at a rapid rate. It was already well on its way to solidifying into a widely accepted fact. Now, calling it misinformation is not to say that it is disinformation, which is when an author purposefully misinforms – it is impossible for me to say, and I’m not even sure it really matters.

I left open the possibility that there was evidence the author had read but then simply failed to cite properly. I constantly used the phrase “no evidence presented”. That is not the same as “no evidence”. Misremembering a citation or even just accidentally deleting one in the process of editing and re-editing a piece is all too easy, and I’m not embarrassed to say that I’ve done it a few times myself. If I were shown that there was evidence after all, it would then have been on me to update and perhaps even withdraw my critique — it would have been embarrassing not to, and with the public so interested in the matter I’d have had nowhere to hide! They’d never have let me forget about it. But until shown otherwise, I judged it to be misinformation.

And I think we should try to correct misinformation when we see it, regardless of its source or whether it was produced with the best or the worst of intentions. It behoves us when we have the expertise and have already done the work to verify – or in other words, when we have the means. And it especially behoves us to correct misinformation when it looks like it’s becoming widespread. If someone’s completely wrong paper is likely only going to be read by them and their Mum (that’s British for Mom), then it may not be worth going to the trouble of correcting it. If it’s been seen by hundreds, thousands, or even millions of people, however, and is being taken seriously, then that’s another matter.

Which brings me back to proportionality, which I think is determined by two factors: 1) the size of the audience it has already reached, and 2) the ease with which the most influential source of the misinformation can be changed.

Had Bulstrode’s theory been contained in just a tweet or a blogpost, I’d probably have just written to her directly and privately. I might not even have bothered to do anything at all – tweets and blogposts are not generally the stuff of which widely accepted facts are made, even if they go viral. And they’re easily deleted or changed. I quietly inform people of errors all the time, and people do the same for me – it’s like telling someone they have spinach stuck in their teeth. It may feel awkward to do, but you’re really doing them a favour.

This, however, was another matter entirely. Not only had the information already reached a vast number of people, but published journal articles – particularly in history – are almost never corrected or changed. If they are, it takes months if not years, by which time the genie cannot be put back in the bottle. Under those circumstances I think it’s best to publish a critique pointing out the misinformation so that it can also reach as wide an audience as possible, though the nature of these things is always that the rebuttal will only reach a small fraction of those whom it had already misinformed. My blog will never be able to outdo the sheer reach of The Guardian, nor will it command the authority of a peer-reviewed journal. If anything, to be truly proportionate I perhaps ought to have done even more.

Just look at the vocal reaction of medieval and Tudor historians to the release of a book and Channel 4 documentary by Philippa Langley, the researcher who first came to prominence for her role in the discovery of the remains of Richard III under a car park in Leicester. This time, she’s back in the news to present the evidence that Richard III did not quietly murder his nephews in the Tower of London, but that the two figures we’re used to thinking of as mere pretenders, Lambert Simnel and Perkin Warbeck, were in fact the real princes. The theory, often presented with a great deal of certainty, has achieved a huge level of publicity and is backed by a bemusingly active group of people who want it to be right – Richard III was Yorkshire-raised, and many English northerners bloody love the north and won’t hear a bad word against the only king who may plausibly be called one of their own.

So other historians concerned about misinformation express their concerns publicly. They do not, and should not, merely write privately to Langley. Suppose she were to be convinced she’s wrong? What’s she supposed to do, somehow track down everyone who’s read her books and tell them to chuck it in the bin? Tell people to unwatch the documentary? No. The genie is out of the bottle. And so we instead have a lively and (largely) healthy debate played out in public – just as it should be. When misinformation is widespread, you counter it by spreading the information that is correct.

But the other reason I felt I had done enough is that I was not the only expert to have noticed the problems with Bulstrode’s paper. Back in August I shared a working paper by someone – Oliver Jelf, then completing his dissertation for a research masters from Buckingham University, and otherwise a graphic designer – who had got in touch with me after digging into it further. Jelf did not just read the paper and take everything at face value, but went to double-check some of the key sources it had used, which he also transcribed for anyone to read and judge for themselves. He showed that some of the claims in the paper were not supported by the sources that had been cited, and even that many could not be supported at all. And what he also did was submit his response to the journal that had published the original paper, asking if they would publish it as a response.

I also then learned of yet more critics, of whom I had been completely unaware. I mentioned the names of experts that I cannot help but regard with trepidation. Well, the one for iron is Peter King. There cannot be a single person alive today on the entire planet who knows as much about eighteenth-century ironmaking as him. He has meticulously researched and published on the history of ironmaking for decades, and just a few years ago finished compiling the monumental A Gazetteer of the British Iron Industry, 1490-1815. And there’s Richard Williams, a trained ferrous metallurgist – his doctorate was on the thermodynamics of iron-carbon interactions – who has over the past decade been correcting metallurgical misunderstandings that had crept into the history of eighteenth-century ironmaking.

Within days of the initial press attention for the paper, King and Williams were among a group of experts on the history of metallurgy who were starting to be asked questions about Bulstrode’s paper – including by various industrial heritage sites about whether they needed to update their displays to reflect the paper’s new narrative about Cort. And the information requests kept coming. But, like me, they noticed big gaps in the evidence – along with a great deal more errors, coming from their position of specialised expertise in the practice and history of iron metallurgy. These were the sort of errors that Jelf and I were far too inexpert to have noticed.

King and Williams took the “proper” channels. Their group drew up a brief summary of the paper’s problems and contacted the various newspapers that had covered the matter to issue corrections. They were completely ignored, and don’t seem to have been mentioned even once in any of the press coverage that began to appear in The Telegraph or The Times. They also contacted Bulstrode’s department and the publishers asking them to take down their promotion of the paper, and were again seemingly brushed off. And, of course, they contacted the journal’s editors.

Academia’s natural process of self-correction now seemed to be grinding into gear. Rightly ignoring all the politicised huff and puff on social media or the press, with culture warriors on the one side crowing at how the criticisms Jelf and I had raised were some kind of victory over “woke gone mad”, and those on the other side impugning critics’ motives in questioning the paper at all, it seemed only a matter of time until the editors would decide whether to either publish Jelf’s rebuttal or more thoroughly examine the paper’s evidence and retract it. At most, there’d be a little more huff and puff before the culture warriors on both sides would forget all about their brief interest in 1780s grooved iron-rollers and move onto the next thing to fight over. That would be that. End of story. A barely visible unpicking of a single stitch in the ever-expanding and changing tapestry of what we know about our history.

Bulstrode would probably be a little embarrassed, but it’s not like it automatically invalidates all her other work or the work that she may do in the future. It was only a single paper after all, even if it got a moment in the harsh and uncompromising glare of the public spotlight. Remember that it was more or less accidental that the paper ended up being subjected to so much detailed scrutiny, purely a product of how much attention it received. Yes, she actively pursued the public’s gaze, but I think it’s probably fair to say that like most people she might not have appreciated what that could mean. There’s plenty of absolute garbage that gets published in other papers, which is probably of significantly greater consequence. Some misinformation can quite literally cost lives; I somehow doubt that getting it wrong on the metallurgy of 1780s Jamaica is going to be quite so perilous. But the difference is that hardly anyone has even heard of most papers, let alone actually read them.

As for the journal editors who would decide whether to retract the article, it was they who read the initial draft and decided it was worth reviewing, who chose the peer-reviewers, who decided to publish based on the reviews, and who helped publicise it once it was published. In general, editors wield a stamp of considerable authority, conferring legitimacy on academic work. Because nobody has the time to follow-up on every single thing they read – life’s too short – we rely on editors and the peer-review process to tell us what we can trust, at least relatively. Editors thus bear an immense responsibility. Their overriding duty is to preserve the trustworthiness and integrity of the journal. This is not just a matter of publishing good work – shoddy stuff will always manage to slip through the net – but above all it’s about ensuring that any misinformation is addressed through corrections or even outright retraction. Even if it might take a while.

Given the weight of the responsibility that they must have felt, I fully trusted that the editors would find a way to correct or retract the paper that would save everyone as much face as possible and we’d all move on. That’s just the way the institutions of academia work, right?

Apparently not.

A couple of weeks ago the editors of the journal, Amy Slaton and Tiago Saraiva, issued a public statement. It’s an extraordinary document, which you can read here. On the one hand, they do admit that there is “no direct reference in any source quoted by Bulstrode or in the archaeological record to grooved rollers used to work iron at John Reeder’s foundry”. They also issue a correction to show that, as Jelf had demonstrated, Cort’s cousin did not in fact go to Portsmouth and bring him the news of such an invention for him to then appropriate as his own. Fine. That’s something.

But they then proceed to systematically misrepresent or simply ignore the most important criticisms made by Jelf and me in public, and by King’s and Williams’s group more privately. Slaton and Saraiva instead come out in “unreserved support” for the article. Although Cort’s cousin never went to Portsmouth, their correction is to say that the news of the innovation must surely therefore have been brought to him by the other, completely random ship the author had originally mistaken it for!

Allow me to very briefly address just a single argument – by far the most crucial point that they left unaddressed. Although they openly admit there is no direct evidence, Slaton and Saraiva argue that Bulstrode made a reasonable inference that there was an innovation at Reeder’s Pen. Let’s set aside for a moment that they also say Bulstrode “demonstrates” it, and that the language of the paper has not been updated to show the extent to which this is speculative. The crux is whether she makes a reasonable inference when claiming that grooved rollers were used there to make bar iron from heated bundles of scrap.

If this inference is unreasonable, then the inferences on which the rest of the narrative rests are all completely irrelevant. If there’s no reason to suppose that grooved rollers were used to make bar iron from heated bundles of scrap at Reeder’s Pen, then it doesn’t matter why the ironworks were destroyed, or whether the machinery was taken on board naval ships to Portsmouth, or whether John Cort or some other random ship sailed to Portsmouth or not, or really any of the chain of events by which Henry Cort is supposed to have stolen the innovation. If there was no innovation there to begin with, then there was nothing for Henry Cort to even steal.

The editors, and Bulstrode herself, make the inference based on the following: that grooved sugar-cane rollers were being made at Reeder’s Pen, that the black workers there thought sugar and iron were in some sense related conceptually, that the ironworks was profitable, that it recycled scrap iron, and that the ironworks used rollers – a technology they admit had been used in ironmaking for centuries, though usually with flat rollers.

They seemingly consider this to be sufficient to “conclude” that the workers “who were so familiar with both sugar and iron production overlapped in their approaches to the two operations and passed bundles of scrap metal through grooved rollers”, thus inventing a grooved rolling technique for iron that Cort later patented in 1783.

This is already tenuous at best. But the editors were also made aware of a host of further problems:

One is that there is actually no mention in the sources of any iron rollers, flat or grooved or otherwise, in use at Reeder’s Pen at all – as Jelf very clearly demonstrated. But Slaton and Saraiva just totally ignore this, repeatedly asserting that the sources show the foundry “used rollers to produce iron goods”. In doing so, they merely reproduce the misinformation we were trying to correct. It’s not like they even contest our reading of the sources or provide new evidence on this point. In fact, they seem to fully accept the accuracy of the source transcriptions that Jelf appended to his paper. After all, they corrected the factual error he’d pointed out about the ship and admit the lack of any mention of grooved iron rollers in use. So they’ve been extraordinarily careless.

Instead of any rollers, King and Williams noted that the evidence relating to Reeder’s Pen is perfectly consistent with it having consisted of a water-powered bellows, chafery and helve hammers, along with an air furnace – old and well-known technology which is all you’d require to process scrap iron.

The editors also ignore the countervailing circumstantial evidence Jelf raised, that at no point did Reeder, the owner of the ironworks, who later even had a patent related to sugar, make any mention whatsoever of any innovations when he was begging the government for restitution for his demolished works. Considering he had every incentive to over-claim for what he had lost, why is there no record of any novelty? If Cort had copied a technology invented by Reeder’s slaves or other workers, you’d think he’d have made a very big deal of this. Again, Slaton and Saraiva simply ignore this point.

So the circumstantial evidence we’re left with is this: there was an ironworks, it was profitable, it probably just used old, well-known iron technology – and we have absolutely no reason to believe otherwise. Oh, and there were sugar rollers.

This is where it gets even more tenuous, and where they misrepresent my arguments. Slaton and Saraiva note, as I had pointed out, that when you roll iron the rollers must be horizontal. They also note that sugar rollers were typically vertical, but that by the late eighteenth century they were sometimes horizontal – which from the way they write it, they make seem like a refutation of an argument, when it is actually explicitly what I said back in July. To very tediously quote myself: “Such [sugar] mills could have the rollers either vertical or horizontal (but they’re almost always shown vertically).” (One of the fun things about substack is that because this blog also gets sent out as an email, about 20,000 people can even go and see the original version, just in case you suspect that I made any edits after the fact. And yes, that exact quotation is there.)

But what they ignored is what is most important – and is precisely what I had said was most important. Sugar rollers and grooved iron rollers of the kind Cort made use of were just fundamentally different. Maybe the source of confusion is in the use of the word “roller”. Sugar rollers were really sugar-cane crushers – their grooves were cut along the length of the rolls, to grip and squeeze. Iron rolling, instead, involves running hot iron bars through the gaps in grooves that run around the circumference of the rolls. Rolling iron through these gaps does not crush, but sort of stretches and smooths the sides and edges of the heated metal – that is what made Cort’s rolling process useful at all, so that the bars it produced became welded without any cracks.

So even supposing you did have specifically horizontal sugar rollers there – and there’s no evidence to suggest even that, other than wishing it were true – then it’s really a matter of simple physics. Pass a heated bundle of scrap iron through a rolling sugar-cane crusher, rather than something that will stretch and smooth the sides and edges of the heated metal, and you are almost certainly just going to break the machine. The idea that sugar crushers were used to invent anything even remotely similar to Cort’s rolling process is thus simply implausible – it doesn’t matter if the black workers at Reeder’s Pen conceived of sugar and iron as conceptually related in any way. It just wouldn’t get you to that technology.

Incredibly, even in misrepresenting my arguments Slaton and Saraiva manage to make a sloppy error, even if it’s not a significant one. In their pretended “gotcha” to point out that horizontal sugar-cane crushers had been in use in the Caribbean by the 1780s, their proof is that “the first patent for horizontally positioned grooved rollers for processing sugar cane was granted to George Smeaton in 1754”, for which they give three citations. Except that they can only have actually checked the first of these: had they bothered to double-check this information, which would have taken all but five minutes of googling, they’d have noticed that it’s actually the famous engineer John Smeaton, not a George, and that he had no patent of this kind. They’d have noticed that this was probably a garbled reference to when John Smeaton in 1754 made drawings for a Mr Grey of Jamaica of a breast-shot waterwheel to power a three-roll horizontal sugar-cane crusher. They’d have noticed that Smeaton never went to Jamaica, that these drawings are marked “not executed” – that is, not actually made – and that mills on this model began to be produced in numbers only after 1794, though a few had seemingly been in use in French-ruled Haiti.

Anyway. We so rarely get the privilege of finding a smoking gun. Usually, the best we have to deal with consists of the kinds of snippets here and there of circumstantial evidence, informed by our wider, contextual knowledge. Writing about history is a puzzle where we lack a great number of the pieces. But what we have here is not just the lack of a smoking gun. There isn’t a body, and there isn’t even any blood. There hasn’t been report of a loud bang, or really anything at all. There’s just a quiet, empty street to which someone has turned up before suddenly rushing to the other side of town and arresting a random person – Henry Cort.

To my amazement, in a true testament to the power of public history, a great many people had apparently carefully read Bulstrode’s paper, my critique, and even Jelf’s paper. Before I’d even had a chance to begin writing up any of this, the public actually noticed some of these glaring omissions and began to raise them in response to the editorial. (Here’s just one example, albeit behind a paywall, on a newsletter by a non-historian that is about seven times the size of mine.) When everything is conducted in the open, where the arguments can be read by everyone, the public becomes like the all-seeing eye of a deity – there is simply nowhere to hide, and they are not to be treated like fools. When I make mistakes, they do the same to me.

Now, many of the people who noticed the editorial’s omissions will, I’m sure, be among those who want the paper to be wrong. But even suppose you had ninety-nine people attacking you with pure, unhinged, loathsome bile, if there were even just a single reasonable person who came to you with a compelling, evidence-based critique, then you’d still have to take that one voice seriously. If I say something ludicrous like “steel and iron are always the same” and ninety-nine people merely call me an idiot without elaborating, I can’t just dismiss Richard Williams when he pops up terrifyingly in my inbox with dozens of carefully reasoned pages explaining how they’re actually rather different.

To add insult to injury, Slaton and Saraiva impugned the motives and credentials of all the paper’s critics, seemingly associating any criticism with the horrid online abuse that a paper so widely publicised inevitably attracted on social media. In the case of Jelf, they even say they were “unable to ascertain” his academic or institutional affiliations, despite the fact he had emailed them directly to submit his paper. So they actually corresponded with him but then simply never bothered to ask, deploying their position of authority to sow doubt. (To my disbelief, though to his great amusement, I’ve even seen it speculated online that I invented Oliver Jelf. I’m not entirely sure why I’d need to invent a pseudonym with such an implausible-sounding backstory, having already put my name to a critique of the paper. Why on earth would I myself actively reduce the authority of a critique that I believe to be sound?)

But what most outraged many members of the public was the way the editors concluded, despite having repeatedly admitted that there was no direct evidence for the article’s claims. I will quote the last paragraph in full:

We by no means hold that ‘fiction’ is a meaningless category – dishonesty and fabrication in academic scholarship are ethically unacceptable. But we do believe that what counts as accountability to our historical subjects, our readers and our own communities is not singular or to be dictated prior to engaging in historical study. If we are to confront the anti-Blackness of EuroAmerican intellectual traditions, as those have been explicated over the last century by DuBois, Fanon, and scholars of the subsequent generations we must grasp that what is experienced by dominant actors in EuroAmerican cultures as ‘empiricism’ is deeply conditioned by the predicating logics of colonialism and racial capitalism. To do otherwise is to reinstate older forms of profoundly selective historicism that support white domination.

Overall, there is not a single worse strategy that the editors could have chosen if they wanted to protect the paper from further, hostile criticism. Not only did the conclusion immediately lead to charges that they were putting politics above evidence, but it also provoked headlines and outraged reactions in the press.

None of this was necessary. Even if the editors had not wanted to retract or make sweeping corrections – though I still can’t see why not – they could have found a way to condemn the personal attacks on the author while then publishing one of the carefully assembled critiques that had been sent to them and allowing the author to then reply. Or they could have even gone further, going through the evidence-based critiques point-by-point, offering new sources where they were lacking, and defending or correcting each point. But they simply chose not to.

And that choice meant that they leaned on their authority, deploying the trust that we all have that the process is still working. The author’s department immediately issued a press release saying that she had been “fully vindicated” and that all the fuss on social media and the press had been the result of “a hostile and organised response from a small number of people”. Much, much more seriously, last week the council of the British Society for the History of Science (BSHS) – not just some informal gathering but an officially registered and rather venerable learned society aiming to speak for an entire sub-field – issued a statement flatly condemning Bulstrode’s critics for having “neglected both common courtesy and established academic standards, including principles of peer review … We strongly condemn unwarranted attacks on authoritative and innovative research of any kind”.

Now, I realise that there was a lot of hatred on social media from those who wanted the article to be wrong. Possibly there were more serious threats and complaints made by the mad, bad and sad as well. But with these kinds of statements they have also impugned the motives and integrity of all critics, no matter the quality of their criticism.

And in so doing they have quite dramatically raised the stakes, and with an extraordinary feat of engineering turned a mere molehill – what should have been a “nothing-to-see-here”, mildly reassuring event of academic self-correction and basic accountability – into a mountain. And a mountain from which there is no easy way down. How can they possibly have expected the people who made detailed, still unanswered criticisms not to respond by merely pointing out what is already so obvious even non-expert members of the public? And if the paper remains demonstrably wrong, where do the editors of History & Technology and the council of the BSHS go from there? This is no longer about whether a paper with an eye-catching argument is wrong or right. They allowed themselves to get sucked into the culture warriors’ silly parlour game and totally lost sight of what really matters, because it’s now about whether the run-of-the-mill procedures for getting academic work corrected or retracted actually work at all. It’s about whether they deserve our trust.

I do not wish to get carried away here and claim that this is proof that the entirety of history is in crisis and we need some kind of radical overhaul. Let’s not throw the baby out with the bathwater. But we do need to be confident that the institutions that produce information and correct any resulting misinformation are working properly. If you care about the history of technology, or the history of the Caribbean, or of slavery, or colonialism, or the history of metallurgy, or even history in general – and they’re all big ifs, but personally I love all history and think it all matters – then much like the public the thing we all have in common is that we want our information to be sound. We will never have it all exactly right, and I’m not saying it will ever be perfect – but I think we all want to be moving in the right direction, stumbling our way towards accuracy and truth, not away from them.

Where do we go from here?

Let’s set aside the details of the particular case. Frankly, I hope I never have to publicly mention it ever again. Third time’s the charm, as they say.

But I hope that there are lessons to draw from this about how to conduct historical debate and truly engage with the public, recognising not just the risks and responsibilities of reaching a wider audience, but the major benefits too.

One thing I noticed a lot in the discussion on social media was the questioning of motives. As I keep mentioning, there are a lot of people out there who for whatever reason, even if you try so hard not to be in any way controversial, will fervently want you to be either right or wrong. So it’s very easy to be tempted into questioning people’s motives, because a lot of people’s motives will indeed stem from politics or ideology, whether that’s obvious or not.

But the questioning of motives is, quite frankly, poisonous. It automatically closes off any chance of healthy or productive public debate. Thoughtful criticism is still thoughtful criticism, no matter its source. Forget this, and we end up in a situation where we assume that criticism cannot be merited, and hubristically close ourselves off to any challenge.

Take Oliver Jelf. I’ve never met the guy. For all I know, he could be a raving rightwinger or a loonie lefty. But it doesn’t actually matter – in all the correspondence we’ve had, but especially in the work that he made public, his respect for the evidence has spoken for itself. Nor does it matter if his name is real or if he’s a former masters student or a grumpy old professor emeritus: it’s the arguments and evidence that count.

We also, I think, need to find ways to make it less embarrassing to correct things. This is not just from a personal point of view, but also from an institutional one. We all know we’re fallible and that we make mistakes all the time. It needs to be easier to admit that, correct the record, and move on. It also needs to be much easier to correct records that have already been published and propagated. This applies to peer-reviewed articles, but potentially all the more so to books.

And we need to brave the public. There’s a risk that this whole saga will put many historians off of actively publicising their work – that they will come to fear the mad, bad, and sad, and all the online abuse it might bring. But I hope it does not. A closed-off history, hidden away behind paywalls or protected by social barriers, is one that will stultify and decay. The public eye may be unforgiving in some senses, but it also exposes your work to new ideas, unfamiliar expertise, and above all creates discipline — if we let it.

So I have a few, tentative commandments of good public history, to which there are perhaps more to add:

Thou shalt not impugn the motives of those who ask awkward questions.

Thou shalt make it easier to correct the mistakes you make.

Thou shalt go forth and publicise your work.

What might I have missed? What else could or should we do to improve public debate around history? If there’s one thing you do, please take a moment to call me an idiot using the comment button, and then tell me why.

And if you’d like to keep up with my research, or support it, please consider subscribing:

I very much hope that the members of the Council of the British Society for the History of Science are reading this, and swallowing hard - indeed I'd like to see it shared and read by all Fellows of the Royal Historical Society as well. It clearly lays out what is really at stake here for our discipline (or what's left of it), gradually and with scrupulous fairness, but the cumulative effect is devastating. As Anton says, lots of rubbish gets published in academic journals in history, and most of it never comes under enough scrutiny to be identified as such. In this instance the author and editors (or the publisher - I co-edit a Taylor and Francis journal, so perhaps I can find out!) actively courted such scrutiny through a concerted publicity campaign which centred squarely on the most explosive claim in the article, namely that Henry Cort had stolen the idea for his patented iron-rolling process from 76 black metallurgists in Jamaica - the subsequent attempt by the editors of the journal to pretend that this was just incidental, and that the main goal of the article was simply to examine the craft skills and practices of these metallurgists on their own terms is entirely disingenuous.

I thought Bulstrode's original article provided worrying evidence of a decline of basic historical logic - it is full of non-sequiturs and dreamy associations of things for which there is no evidence that any real connection existed at all. However it was just possible to believe that it wasn’t a product of deliberate academic misconduct so much as poor historical practice, wishful thinking and the temptations of 'impact' and historical celebrity. I didn’t think it warranted any kind of disciplinary investigation. And like Anton I had thought, naively, that his polite and well-reasoned criticism and Jelf’s review of her evidence (I wasn't aware of the parallel process that King and Williams were conducting behind the scenes)would produce at least a partial retraction, and an admission of carelessness and misreading of the sources, if not of wrongdoing, by Bulstrode. That would have resolved things with minimal embarrassment to all parties.

As Anton says, it is the behaviour of the journal editors, and above all of the Council of the British Society for the History of Science, which has turned this into what is now a genuine academic scandal. They have no factual arguments to oppose to the criticisms he and others have made, and so are resorting to the exercise of naked institutional authority to try to silence opposition or have it dismissed as illegitimate. I'm not a historian of science, but anyone who cares about historical truth or ethics should be outraged by this.

Hi Anton. You're an idiot.

OK. Now we've got that out the way... 😁There's so much here I'd love to comment on, but I'm overdue with my latest newsletter, so I'll try to keep this under 10,000 overexcitable words.

Thank you so much for the mention here! Funnily enough, my "dear reader, call me an idiot" request to encourage readers to break the ice is applicable in my case here: this is the first time I've commented on your Substack, despite being a fan of your work for a long while, so - I'm glad it worked on me as well.

Speaking as someone looking on in semi-clueless horror from the sidelines at the controversy around the Jenny Bulstrode piece - of everyone (including Noah Smith), you've untangled it best for me, so thank you. And it is indeed so horrifying - I can't quite understand how it all became so wayward of the calm, respectful, fact-based and well-publicised discussion that is sorely needed at the heart of this thing. What a mess.

(A rose-tinted personal; memory: as an archaeologist, I was accustomed to blazingly passionate semi-rows happening in the back of pubs where, despite the volume and the colour of people's faces, it was more or less understood that everyone's opinions were flawed and up for correction in service of a keener glimpse of reality, or at least a richer grab-bag of ideas with which to speculate upon it. Especially true of us undergrads, of course, but it applied to everyone, professors included. I really enjoyed that, along with the intolerance of people who held such totally inflexible conviction that they couldn't take part in that kind of good-natured verbal melee. I can't imagine what the best of those folk would make of this situation where fact-based counterarguments are treated with such hostility. Where's the scientific method here? I don't see it.)

Also, congratulations on a hilariously perfect summing-up:

>>"what we have here is not just the lack of a smoking gun. There isn’t a body, and there isn’t even any blood. There hasn’t been report of a loud bang, or really anything at all. There’s just a quiet, empty street to which someone has turned up before suddenly rushing to the other side of town and arresting a random person – Henry Cort."

True Art, that.

Regarding getting things wrong:

I also live in fear of it - but I have it much easier than some, because I'm actively cheating. I'm not doing original research like you are - I'm presenting myself as an amateur enthusiast in what I write about (which I am, 90% of the time) and this gives me leeway to mea culpa myself out of any holes I've dug myself into. That has proved immensely useful AND it's helped my engagement hugely, because it's a chance to immediately issue a follow-up where I correct the facts and point to the egg on my face, and *that* is when I get emails saying they enjoy my work. It doesn't make me cringe any less when I realise I'm dead wrong, but it does humanise me and give me a chance to show I'm genuinely correctable...

But to your wider ethical point, it's very much how I want to present myself online, based on my time as an archaeologist. My first few terms as a student in York (200-2004) were a dizzying tour in how the principles of Archaeology had been overturned or undermined again and again throughout the 19th and 20th Century - from the data-driven law-seeking rationalism of so-called Processual methods to the new wave of ideas coming from the sciences, from the Annales school, from sociology and gender studies, now messily lumped together under the term "Post-Processual". In short, we were taught how to consider everything at least a bit wrong and *still* move forward, how to put our full weight on that uncertainty and how to think like the idealised scientist, where everything is a working hypothesis, where the difference between necessary speculation and vital fact is clearly understood and we're always trying to tell one from the other, and (the classic final line of every undergraduate thesis) More Work Needs To Be Done. So I guess I've brought that forward in a way I'm only partly conscious of, and it helps me be less afraid of getting things wrong in public. But it's also cheating, because I'm making it very clear that I'm a student, as befits a privileged enthusiast's newsletter about the science of curiosity itself. That's the wall I get to hide behind. So far, barring a few hundred people calling me an idiot, nothing nasty has kicked off yet. Time will tell.

(I did defuse one argument about one of my newsletters on Twitter where someone yelled "WOKE RUBBISH You don't know what you're talking about you ****ing libtard" and I replied "I completely agree!" and included a short summary of things I'd learned were incorrect in my piece. I didn't get a reply from him - I guess because he had no actual interest in what I'd got wrong? Anyway, that worked. Make me feel nice. Might use again.)

Your final suggestions about how to improve public debate...it makes me wonder, is there something more we can do to teach a more academic approach to critical thinking? I know it's often said that "young people don't know how to think critically" and so on, which is a loaded statement if ever there was one, and I'd encourage anyone of my generation (50s) to have someone under the age of 30 do, say, some technical troubleshooting for them on their phone before chucking such a sentiment around. But it does make me wish that the groundings I got in my first terms as an archaeology student - the acceptance of ever-present personal bias, the recognition of the nature of primary, secondary & tertiary sources, a willingness to play with ideas without calcifying any of them into dogma, and an eagerness to discuss or even argue in good faith - I wish there was something in an easily-digestible popular format that was flooding TikTok and Facebook and everywhere else, baking these principles deep, and presented in a way that was just as emotionally engaging as the bad-faith misinformative nonsense turning heads of every generation...

(For example, it was heartening to see the organisational psychologist Adam Grant championing the scientific method as a way of improving our ability to rethink, in his recent bestselling book "Think Again". Where's the history-based version of this? Is there one? Maybe you could write it, Anton? OK, OK, I'm leaving now, I've done enough damage to your comment thread.)