You’re reading Age of Invention, my newsletter on the causes of the British Industrial Revolution and the history of innovation. This edition went out to over 24,000 subscribers. To support my work, you can upgrade your subscription here:

I’ve lately been reading about one of history’s greatest spies — not a James Bond-like agent with licence to kill, but a master of industrial espionage, John Holker.1

Holker was originally from Manchester, in Lancashire, where he was a skilled cloth manufacturer in the early eighteenth century, his specialty being calendering — a finishing process to give cloth a kind of sheen or glazed effect. But Holker was also a Catholic and a Jacobite — a believer in the claim of the Catholic descendants of the deposed king James II to be the rightful rulers of Great Britain, instead of the Hanoverian George I and George II who had only succeeded to the throne because they were Protestants. In 1745 James II’s grandson Charles, also known as Bonnie Prince Charlie — likely the “Bonnie” who lies over the ocean in the famous song — landed in the Scottish Highlands and raised the royal standard. Charles’s uprising defeated the British troops stationed in Scotland, captured Edinburgh, and then marched down the west coast of England, capturing Carlisle and entering Lancashire.

To Holker, who had been born in the same year as the last Jacobite rebellion in 1719, the arrival of Charles in Manchester must have seemed like a once-in-a-generation opportunity. He and his business partner instantly joined Charles’s troops and he was appointed a lieutenant. But Manchester was the last place to provide many eager volunteers for the uprising, and when Charles reached Derby he lost heart and turned around. Holker and his business partner ended up being left to garrison Carlisle as Charles and his force retreated into Scotland to hunker down, and they were soon captured by the British troops sent to quash the uprising. They were then, as officers, sent to Newgate prison in London to sit with their legs bound in irons and await trial and certain execution.

But they never made it to trial. In the first demonstration of Holker’s extraordinary talent for espionage, they escaped. Holker had been allowed visitors in prison, so had drawn on London’s crypto-Jacobite circle to smuggle in files, ropes, and information about the prison and its surroundings. They managed to file through the leg-irons and window bars, climbed up the gutters onto the prison roof, and then used planks from the cell’s tabletop to cross onto the roof of a nearby house. In the event, they disturbed a dog guarding the house, and so Holker hid in a water-butt and became separated from the others. He eventually found refuge at a crypto-Jacobite’s house, then escaped into the countryside before managing to make his way to France.

In France, Holker joined his fellow veterans of the failed uprising of ‘45, becoming a lieutenant in a Jacobite regiment of the French army. He fought for the French in the Austrian Netherlands — present-day Belgium — against the Hapsburgs, the Hanoverians, the Dutch, and the British. Even more extraordinary, however, was that when Bonnie Prince Charlie wanted to go in secret to England in 1750, it was Holker who went with him as his sole companion and guide. Although Charles failed to persuade his supporters in England to rise up in rebellion on their own, Holker managed to get the prince secretly and safely to London and back.

By the time Holker reached his early thirties he had been an industrialist, rebel, prisoner, fugitive, soldier, undercover agent, and even spy-catcher: he successfully identified a spy for the British in Charles’s circle, even if Charles failed to heed his warning. But in 1751 Holker’s career took yet another turn when he was recruited by the French government as an industrial spymaster.

Holker’s chief task was to steal British textile technologies.

Now, this may seem surprising to some readers. After all, most people have a rough notion that Britain’s Industrial Revolution began in the 1760s with Watt’s improvements to the steam engine, the proliferation of coke-smelted iron, and especially the invention of various textile-related machines. The textbook examples are Hargreaves’s spinning jenny, Arkwright’s spinning frame, and Crompton’s combination of their two principles in the spinning “mule” (being a cross of a male donkey with a female horse).

But the reality is that long before 1760 Britain was, for a great many industries, already widely acknowledged to be at the forefront of European technological development. It had had this continent-wide reputation since at least the 1710s, if not even earlier, when the French, Spanish, and Russian governments systematically attempted to steal its technologies.

The list of British industries and inventions that were worth copying in the 1710s gives us an idea of its lead: iron founding, anchor-smithing, steel-making, file-making, brass lock-making and hinge-making; clock-making and various aspects of watchmaking, including spring-making and watch-wheel cutting; sailcloth-making, ship-building, and the steam-heated bending of timber for making barrels and ships; the newly-invented Savery- and Newcomen-type steam engines; and flint glass-making and tobacco processing too. It also, significantly, included various parts of the textiles industries including wool-combing, weaving, shearing, and finishing.

The French were still attempting to catch up with many of these industries many decades later in the 1750s when Holker appeared on the scene, by which time the list of British industries worth emulating had grown. Among textiles alone, the list had expanded to include dyeing and bleaching techniques, the use of flying shuttles in weaving, making of blankets and coverlets for beds, webbing with which to upholster chairs, and the finishing of leather. It also included the making in Lancashire of cotton-based velvets as a cheaper and sturdier alternative to silk in gentlemen’s waistcoats and breeches, as well as fustians — a kind of cloth made by weaving cotton with linen into a twill, encompassing jean, corduroy, and knock-off velvets like velverets and velveteen.2 The general British lead was not easily overcome, not least because its industries were themselves proliferating and each continuing to improve.

But John Holker was the man to help close the gap. As well as having a talent for espionage, his original profession had after all been in the Manchester-based textile industry that the French so hoped to acquire — especially cotton velvets. In 1751 he returned to England, travelling to Lancashire to make rudimentary models of some of the machinery, buy samples of yarn and cloth and bits of machinery to serve as patterns, identify some skilled workers who might be enticed over to France, and start to build up a network of agents in London and Lancashire who could then continue the work in his absence — cleverly, he aimed to have at least three or four agents so that competition would drive down their fees. (Incidentally, Holker’s espionage has turned out to be a goldmine for historians who want to know more about England’s textile industry. A facsimile and transcript of Holker’s manuscript album of cloth samples from his 1751 trip, along with specialist analysis, was published just a few months ago — it’s thanks to Holker that we have the oldest known surviving sample of jean!)

Setting up a network of agents in England was just the beginning, however. The real challenge was in adapting the stolen technology once it had been brought to France.

Holker’s network managed to entice a small colony of some thirty people over to France: over a dozen workers involved in the making of cotton velvets, including weavers, dyers, fustian cutters, loom- and calender-makers, and calenderers, along with their wives and children. Holker arranged for their travel, accommodation, and other expenses, as well as sourcing the right tools for them.

But he also needed to ensure that their skills were spread to French workers. This required a skilled interpreter — he recruited an English silk worker who spoke French, and was thus versed in the jargon of the textile trade in both languages — and most importantly it required the right incentives. The English workers feared that once their skills had been adopted by their French counterparts they would instantly be abandoned, left jobless in a strange land and despised as traitors back home. Some of them took the precaution of adopting pseudonyms, lest their acts of industrial treason be discovered back home — since 1719, after the first major wave of French industrial espionage, Britain had made the emigration of skilled workers illegal.

The English workers were therefore paid high salaries, awarded bonuses for their successes, and given generous welfare benefits — they were offered retirement pensions at half their salary, which would be continued to their widows, as well as pensions if they became unable to work through illness. They were also paid bonuses for every French worker they trained.

As for more general financing, the French government wanted the cotton velvet industry to become general throughout the country rather than being confined to a single monopolist protected by patent — the typical means by which cash-strapped states had tried to persuade private capital to take on the risks of technology transfer. So the French government paid for the wages and pensions of the English workers at private cotton velvet factories, as well as paying them bounties for reaching certain benchmarks over the course of ten years for reaching a certain number of cloths per year and putting a certain number of machines into operation. Instead of using monopoly, they subsidised access to skills and provided benchmark-related grants.

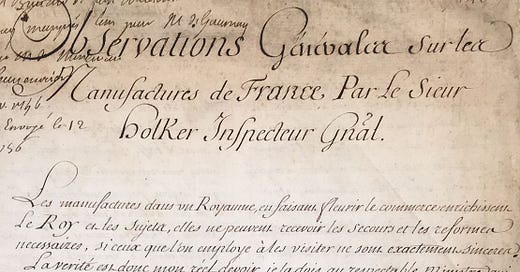

The introduction of the cotton velvet manufacture was on the whole a success, and Holker was in 1755 promoted to the post of Inspector-General of Manufactures. He thus progressed beyond industrial spymaster to become a sort of innovation inspector, touring France to give advice on how to catch-up with and then outcompete the English — not just in textiles, but in everything from watermills and hardware manufacture to rearing livestock. Where possible, Holker’s method was to procure equipment and find skilled people to actually demonstrate the techniques he recommended — by far the best way, in his experience, to overcome any scepticism by local workers and see that his advice was actually adopted. Seeing was believing.

Holker’s own son, John Holker junior, followed in his footsteps as an industrial spy, in the 1760s and 70s helping him introduce to France the British methods of manufacturing sulphuric acid. Holker thus established a dynasty, and indeed a noble one. In 1774 Holker was officially “recognised”, having somehow established a rather dubious aristocratic pedigree via the English College of Arms, as being French nobility — a fittingly implausible peak to an astonishingly effective career.

If you’d like to support my work, please consider upgrading your free subscription to a paid one here:

Unless otherwise stated, I’ve drawn much of my information on Holker and the industries that the French attempted to copy from John R. Harris, Industrial Espionage and Technology Transfer: Britain and France in the 18th Century (Taylor & Francis, 2017), particularly chapter 3

The history of the term “fustian” is pretty complicated, but this seems to have been the prevalent definition in 1750. I’ve based my definition here on Philip A. Sykas, ‘Fustians in Englishmen’s Dress: From Cloth to Emblem’, Costume 43, no. 1 (2009), pp.1–18; and John Styles, ‘Re-fashioning Industrial Revolution: Fibres, fashion and technical innovation in British cotton textiles, 1630-1780’, in Giampiero Nigro ed., Fashion as an economic engine: process and product innovation, commercial strategies, consumer behavior (Firenze University Press, 2022), pp.45-72

This makes me wonder about other technology, like grain/wheat milling?

Until the late 20th century, Australian department stores directories listed all cotton goods as 'Manchester'.

So, to us colonials, that's what it was.