Age of Invention: The Dutch Wheel of Fortune

Another remarkably early proto-steam engine; and a sneak peek of the earliest ever drawing I've found of a large-scale version - from France

I’m working on an exciting and top secret project right now, which has involved double- and triple-checking exactly how the earliest steam engines worked. As I noted in my three-part series on why the steam engine wasn’t invented earlier (I, II, III), people were developing machines that exploited atmospheric pressure decades earlier than the standard story suggests. Decades before Torricelli’s 1640s demonstrations that the atmosphere had a weight and that vacuums were possible.

I found quite a few early examples for that research, some of which had never been noticed before. And now I’ve stumbled across even more!

One of these — though not the most remarkable one — is in the diary of the Dutch scientist Isaac Beeckman. I was originally reading the diary for clues about the working of Cornellis Drebbel’s famous 1606 perpetual motion machine, which exploited changes in temperature and atmospheric pressure to keep clockwork running, and which had water go up and down in a circular tube, seemingly in concert with the tides. Beeckman doesn’t seem to have seen Drebbel’s machine personally, but his diary was full of useful speculations about how Drebbel must have done it.

In the process of speculating about Drebbel’s machine, however, Beeckman in 1622 appears to have independently invented yet another early Savery engine — the first widely-used practical steam engine — decades before Torricelli. To quickly explain, Savery’s engine operated by admitting steam into a chamber, then spraying it with cold water to condense it. This created a partial vacuum within the chamber, causing water in a cistern below to be sucked up a pipe. By reducing pressure within the chamber, it exploited the relatively higher pressure of the atmosphere on the surface of the water in the cistern. Then, hot steam was readmitted to the chamber, this time pushing the raised water even further up through another pipe above.

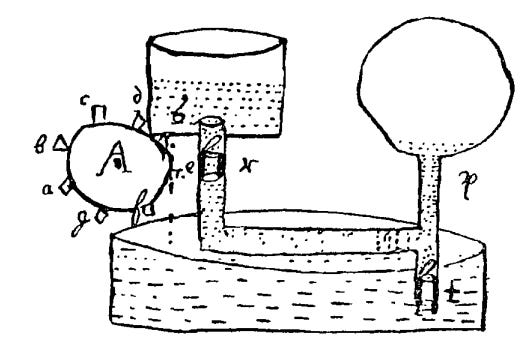

Beeckman’s engine did essentially the same thing, and even thought of using the raised water to drive a waterwheel. He labelled it motus perpetuus in rota — a wheeled perpetual motion. Here’s his sketch: