Age of Invention: Thread of Gold

You’re reading Age of Invention, my newsletter on the causes of the British Industrial Revolution and the history of innovation. This free edition went out to 7,400 people. You can sign up here:

When England’s Parliament met in 1621, it was mainly supposed to vote king James I the funds to fight a war. His daughter’s domain, the Palatinate of the Rhine, had just been invaded, and the European Protestant cause was under grave threat. As I set out two weeks ago, however, the House of Commons had seized the chance to pursue a scandal. Jealous of the Crown’s challenge to their status as local power-brokers, and hoping to embarrass the king’s favourite, the Marquess of Buckingham, MPs opened an investigation into Sir Giles Mompesson’s patent to license inns.

When it came to inns, I argued that the case against Mompesson was flimsy (making me perhaps the only person to have defended him for over four hundred years). He appears to have been a trusted and able bureaucrat, the source of his downfall being his sheer effectiveness. But the flimsiness of the case against him was not enough to stop the political witch-hunt. Next on the list was a project he had administered for making gold and silver thread.

It sounds obscure, and I was fully expecting to write up a short overview of a niche industry that just happened to be thrust into the limelight of 1620s politics. That was a month ago, when I first started drafting this piece. But pulling on the golden thread revealed a desperate, decade-long battle between the City and the Crown, over who would get to control the financial stability of the realm. I’m sorry for the delay in publishing it, but I hope I’ve made it worth the wait.

Gold and silver thread was a luxury product that adorned the clothes of the ultra-rich. Made famous by Greece and Cyprus in the Middle Ages, it was soon being produced in France and Italy too, and by the seventeenth century was often known as simply “Venice gold.”

There were two main methods of producing it. One was to take thin sheets of the precious metals and beat them into a foil upon vellum or stretched-out animal gut, to cut the foil into thin strips, and then “spin” the strips by winding them around a textile core, typically of silk. The gold or silver thread could then be embroidered onto clothes. The other method was, more accurately, to manufacture gold and silver wire, drawing rods of the heated metals through smaller and smaller holes. The English had been drawing gold and silver wire since at least the fourteenth century,1 though the technique of making it into thread was seemingly introduced to London in the 1440s by two brothers fleeing the dying Byzantine Empire, Alexius and Andronicus Effomatos — a remarkably late case of direct technological transfer from the Byzantines to Britain.2

Despite that transfer, by the end of the sixteenth century the industry was still not very established in England. Although the goldsmiths of London’s ironically-named Cheapside were famous for their sophisticated wares, gold and silver thread was still largely being imported from Venice. So it doesn’t seem all that surprising that the king, in 1611, granted a group of London-based merchants a 20-year patent monopoly to introduce a foreign technique for making the stuff — allegedly the spinning method. On the face of it, it looks like a typical attempt to create a domestic substitute for expensive foreign imports, moving English cloth manufacture as far as possible up the value chain. It’s exactly the sort of thing that patents for invention were for.

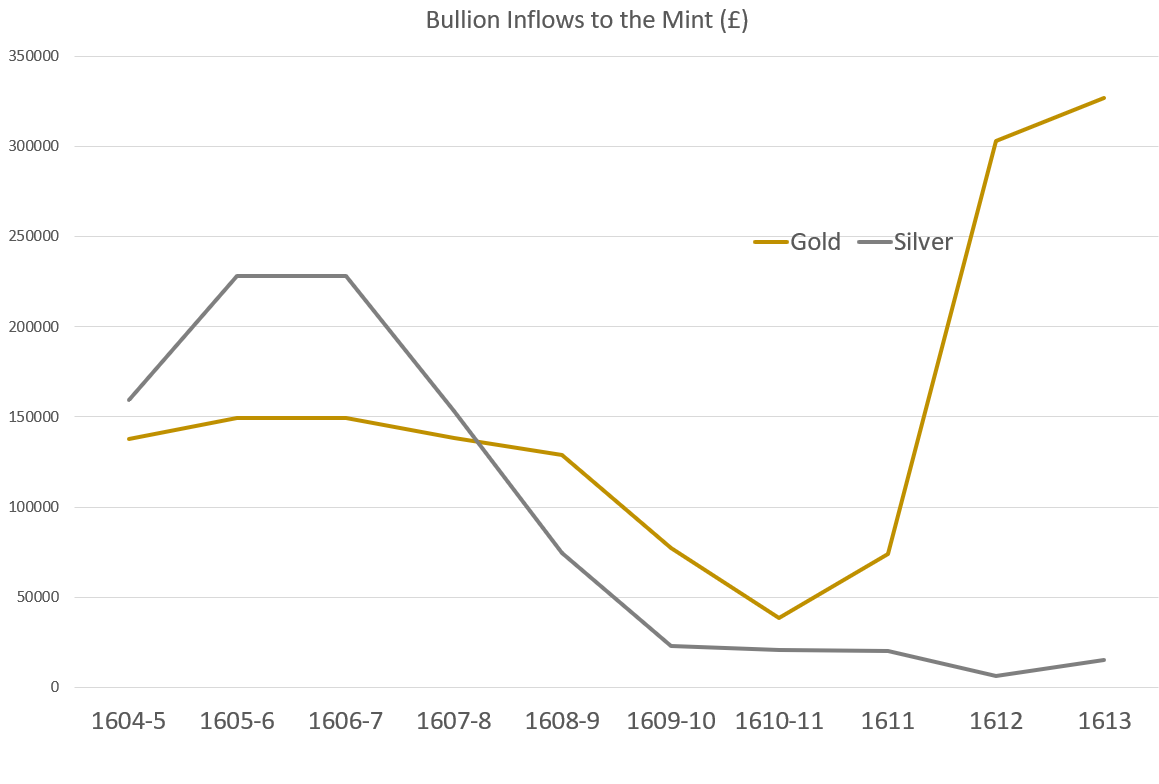

But 1611 was also a remarkable year in England when it came to gold and silver. For the last few years, the king’s ministers had been becoming concerned at a dramatic fall in the amounts of bullion arriving to be stamped into coins at the royal mint. Tucked away in the Tower of London, the mint was the primary agency through which the Crown tried to control the economy. In an age before deposit banking had become widespread, before central banks, when credit only rarely circulated as currency, controlling the coinage was one of the only available levers of monetary policy — really, one of the only levers of macroeconomic policy at all. (When it came to fiscal policy, the lever barely existed: government spending as a proportion of the economy was miniscule, and few dared lend to the Crown voluntarily.)

The first signs of trouble might have been when the silver arriving for coinage roughly halved in 1608-9, and then halved again the following year. Silver coins were, by far, the kind used by most people for most payments. Gold was only really used for major transactions. Using a gold coin would be worse than trying to use a £50 note at a food stall — I once had to do this, and earned myself a very stern glare. But the fall in incoming silver seems to have then stabilised in 1610. It may just have been the transitory effect of a very poor harvest in 1608, when silver had instead flowed abroad to buy imported grain. At a time when food and beer made up 75-85% of the typical person’s expenditure, and when agriculture still employed over half the working population, the quality of the harvest could cause dramatic fluctuations in the wider economy. Inflation in the bad years, deflation in the good. (Incidentally, a national system of granaries was often mooted, but never came to fruition — not just as a way to prevent shortages, but to smooth out the year-to-year economic fluctuations from good and bad harvests.3)

It would not have helped, either, that the Dutch Republic had also just signed a twelve-year truce with Hapsburg Spain. Freed to compete, the Dutch suddenly pushed English exports out of markets all over Europe. Permanently lower exports, after a sharp increase in imports, perhaps explains why silver flows to the mint merely stabilised after 1610, rather than recovering.

But then, just before the silver inflows stabilised, in 1609 the flow of gold to the mint began to dwindle as well. The bad harvest and trade situation may have been to blame for this, at least initially. If the whole economy imported more than it exported, then we might expect both silver and gold to have flowed abroad to pay for the excess imports. There’s a reason seventeenth-century policymakers were so concerned about trade deficits. If a country had a sustained and significant trade deficit, then a country like England — with barely any gold or silver mines of its own — might end up without money.

This sounds like an exaggeration, but there were few good alternatives to silver or gold. Copper or lead coins may have offered one alternative, but were far too easy to counterfeit. Even over a century later, despite various technological improvements, Britain had as many counterfeit copper coins in circulation as legitimate ones.4 Adopting copper in the early seventeenth century would thus have been tantamount to the Crown simply giving up its control of monetary policy entirely. Copper coins did exist already, but only as semi-official tokens used by particular cities like Bristol or Norwich, or as unofficial tokens used by particular tradespeople. They were ultimately only used for the smallest of small change, or in mid-sized communities where you already knew and could trust the issuer. And as for paper currency, this required credit institutions to be sufficiently well-developed and widely used. Credit-based currencies only really began to become possible in England much later, in the 1660s.

The loss of bullion, then, thanks to a large and persistent trade deficit, appeared to threaten the disintegration of the national economy: a forced reversion to much more localised, trust-based exchange, and in some areas perhaps even barter. Although trade might inevitably re-balance before bullion completely fled, the likely short-term pain — deflation, bankruptcies, economic contraction, unemployment, and rioting — were so potentially catastrophic as to be worth avoiding.

Yet in 1610-11, gold flows to the mint continued to plummet while silver levelled off. It no longer seemed like there was a trade deficit, at least. Good news for the economy. But the falling inflow of gold was still a problem for the Crown. Gold may not have been terribly useful for ordinary transactions, but it accounted for a large chunk of the mint’s profits. Although these profits were never huge, they were a reliable source of revenue — especially at a time when king James I was especially strapped for cash. By 1610-11, with so little gold flowing in, the mint was close to even making a loss.

So why wasn’t gold coming to the mint? The way the mint worked was that gold and silver bullion — ingots, foreign coins, plate, and so on — were brought to it by people who wished to have it converted into coin. The mint offered face-value prices in English pounds, shillings and pence per weight of fine metal. It would then deduct some of that metal to take fees to cover the cost of coinage — often called mintage, or brassage — as well as a tax for the Crown, called seigniorage. But the Crown could not just take all the seigniorage it wanted. England’s mint was also in competition with the mints of other countries, each offering prices and taking seigniorage fees of their own.

This is what mint officials blamed in 1610-11. They noted that the mint in Holland had increased the price it offered for gold, not relative to the English gold prices exactly, but relative to the price that it offered for silver. Rather that an ounce of gold being valued at about twelve ounces of silver, as by the English mint, the Dutch mint valued it at about twelve and a half. This may not sound like much of a difference, but it created a lucrative opportunity for arbitrage. Savvy merchants in England would have realised that they could send their gold to the Netherlands, with which to pay their debts in silver, and their savvy Dutch counterparts would likewise have sent silver to England, where they could pay their trading debts in gold. Gold would have flowed out of England, and silver in — what’s called a bimetallic flow.

To stem the outflow of gold and preserve the mint’s profits, then, James I in 1611 raised the English mint’s own gold/silver ratio in response. But he overdid it, making an ounce of gold worth thirteen ounces of silver — higher than anywhere else. The bimetallic flow didn’t just stop, but reversed. Gold now flowed into England, with silver hardly being coined at all — a situation that continued for the next decade.

Something that puzzled me about this decision, however, and which has seemingly puzzled a lot of other historians, is that the logic behind it seems faulty. Had the Dutch really been guilty of causing a bimetallic flow in 1610, we’d have expected silver to flow into England too, rather than stagnating. And more seriously, the error in over-correcting and overvaluing gold in 1611 was not immediately reversed. Given policymakers were very worried about the harmful deflationary effects of a severe outflow of silver, as described above, why didn’t they immediately act to redress the imbalance?

One potential explanation is that the Crown’s profits increased so substantially from the vast amounts of gold being minted, that the king was unwilling to then give them up. He may thus have decided to sacrifice the economic wellbeing of his subjects for a bit more seigniorage. But this seems far from convincing, as a better balance of gold and silver coinage could also have been lucrative, and the profits were not that significant as a proportion of total Crown revenue — no more than about 2-3%.

Another explanation is that having overvalued gold too far, it was thought economically disastrous to attempt to reverse it. The monetary historian Nicholas Mayhew, for example, argues that policymakers were ideologically opposed to raising the face value of the silver coinage — especially after the disastrous English experience of debasement in the 1540s, under Henry VIII. He compares it to the way the lingering trauma of 1920s hyperinflation affected German monetary decisions in the 1990s.5

But I don’t think this can be right. Debasement was just one of many ways to change the face value of coinage, and policymakers of the time were well aware of this. Debasement involved specifically reducing a coin’s fineness, or precious metal content — something that was relatively difficult to detect. You’d take your bullion to the mint, and receive the same number of coins at the same weight and face value as you were used to in return. But the mint would, unbeknownst to you, have taken a much larger quantity of the gold or silver out of the metal. Unless you actually melted down the coin and tested its fineness for yourself, all but the experts would be none the wiser — unless, that is, so much of the precious metal had been removed that you’d very quickly see the copper showing from just a bit of use.

Debasement was fraudulent. By secretly changing the least detectable aspect of a coin, it was a way for the mint to effectively increase the seigniorage rate, holding back more of the precious metal for the king. Despite its disastrous economic effects, it was a way for the monarch to get rich quick.

But there were other and less destructive ways to devalue coins, and thereby increase the price being offered by the mint for the precious metal within them. For a start, changing the fineness of the coinage could be done transparently, by openly declaring how much less precious metal a given coin would contain. Or the mint could keep the fineness the same and simply reduce a given coin’s weight — say, by decreasing the diameter of a shilling, or making it thinner. This was an even more transparent and immediately detectable method. Devaluation through the loss of weight happened naturally, too, as coins were passed from hand to hand and became worn down. Just as transparently, and most cheaply of all, currently circulating coins could simply be declared to have different values — a process known as calling up / down. “Hear ye, hear ye! A gold crown must now be accepted for only nineteen silver shillings instead of twenty!”6

Here’s a very crude drawing I’ve done of the three methods. Supposing the coin on the remains at the same face value of £1, each method changes the relative value of the gold or silver used to mint it:

So the mint did not need to resort to debasement in order to attract more silver. It did not even have to touch the silver coinage at all. If what mattered for the bimetallic flow was the ratio of gold to silver, it could have simply revalued the gold coins instead, increasing their fineness or weight. In fact, the mint had just ten years earlier enhanced the value of silver relative to gold — without any obviously disastrous effect.7 Policymakers were thus well aware of the methods available to them. There must have been better reasons for the lack of action than just an ideological opposition to increasing the value of silver.

What they must have believed, I think, is that silver was actually already too plentiful in England’s economy. Gold may well have been overvalued by the English mint, and hardly any silver was from 1611 brought to it for coinage. But we need to be careful not to equate the mint with the country as a whole. As a government taskforce to investigate the lack of silver at the mint found in 1612, “it was confessed by the merchants, that silver is continually imported into the realm … much like as in former times”.8 England’s royal mint was not just competing for bullion with rival, foreign mints. It was also competing with other potential uses of silver and gold. It’s here that gold and silver thread comes in.

The main domestic competition for bullion came from the goldsmiths — a catch-all term for all workers in bullion. They paid a premium for the metals, to produce plate like candlesticks and dinner services, or to add gold or silver filigrees and leaf to ceilings, wainscoting, coaches, furniture, armour, weapons, coats of arms, and even funeral monuments. And, of course, they could make gold and silver thread and lace for clothes. The 1612 taskforce summarised the situation perfectly: despite plenty of silver entering the realm, “in respect of the greater price which it has with the goldsmith it cannot find the way to the mint.”

I suspect, then, that policymakers must have feared that with a healthy export surplus and plenty of silver already in the country in the form of goldsmiths’ plate and wares, even a very minor adjustment back in favour of silver might have then unleashed a gigantic torrent of silver to the mint. And given the fairly healthy-seeming state of the economy, a sharp increase in the main circulating medium of exchange would have caused rapid inflation. If bimetallic flows with the mints of other countries could be a headache for policymakers, unleashing the silver stocks of the goldsmiths would have been all the faster and larger. Bullion had to be smuggled across the seas for an international bimetallic flow, whereas Cheapside was just a 20-minute stroll to the mint.

It made more sense, then, not to meddle with the currency at all, but to pull on a completely different set of monetary policy levers — ones that tend to be neglected by monetary historians. These were the regulations of what one could and could not do with gold and silver: laws forbidding English coin from being clipped or melted down, forcing certain kinds of imported bullion to be sent first to the mint, or banning bullion from being exported at all. Such regulations are widely assumed by monetary historians to have been ineffective, and with reason. Bullion very clearly managed to find a way to be smuggled out of the country during a trade deficit, for example, or as part of a bimetallic flow. There was seemingly always somebody both willing and able to break even the harshest of laws, risking substantial fines, imprisonment, or death.

And who more able than the goldsmiths? They were the ones who would exchange your gold coins for silver, or silver for gold. Some would even pay a premium to temporarily get a hold of large piles of coin, and then pay people to sort through them for coins that had been made a little too heavy by accident, or were less worn down by use. These they would then clip for the excess bullion — a process known as culling. The clippings, when melted down, might then be smuggled abroad.9 They might even hide the extra gold or silver in decorated wares, sending them along with ambassadors or merchants as part of their private luggage or as “diplomatic gifts”. Thanks to modern reconstructions of bullion-embroidered clothes, it appears that their stitches used far more gold and silver than was necessary for the decoration.10

Even if the illegal practices could not be entirely eliminated, however, better regulation or enforcement of the existing laws could obviously raise the cost of exporting bullion, or of preventing it from reaching the mint. Such alternative monetary policy measures could well have increased the relative attractiveness of sending bullion through the legal channels directly to the mint — an effective improvement in the prices that the mint could offer.

And this was what made the patent for gold and silver thread so peculiar. Rather than merely a patent for invention, it was actually the beginning of an increasingly ambitious scheme to create a powerful, centralised financial regulator — one that would prevent bullion flowing abroad, and be able to suppress the domestic competition that the mint faced for gold and silver already in the country. It was to become a sort of 17thC version of the UK’s modern Financial Conduct Authority, or the Securities and Exchange Commission in the US. Many of London’s wealthiest citizens were, quite naturally, opposed.

In theory, the regulation of bullion was supposed to be handled by the London Company of Goldsmiths, their guild. But with the initial outflow of silver in 1608-9, it started to look like this centuries-old method of self-regulation had failed. In response to the apparent crisis, the warden of the mint proposed that the Crown create an “Office of the Exchanger”, to remove from the goldsmiths possibility of sorting and culling coins. The goldsmiths put a stop to it with some strong lobbying, and had all their members swear very explicit oaths not to export bullion.11 A few years later, the Crown also granted a patent to two courtiers to create a cheaper alternative to employing money scriveners — another group who, by being entrusted with lots of cash like the goldsmiths, were suspected of dodgy dealing when it came to handling coin. (I wrote about that failed project a few months ago here, before I realised the full implications of its timing.)

But things really got going after 1611, when the mint’s ability to readjust the gold-to-silver ratio became too constrained. Rather than meddle with the coinage and risk inflation, officials concentrated most of their efforts on regulatory means. The 1611 patent for gold and silver thread, which had originally just covered just the newly-imported spinning technique, was soon being used to try and cover the wire-drawers as well. A few years later, the rights of the patentees to punish suspected infringers were strengthened further, with essentially all methods of making gold and silver thread now under their purview. And it was combined with another patent for controlling all gold and silver thread that was imported as well. So long as the patentees could be trusted more than the dodgy-seeming goldsmiths, this was potentially a way to ensure that some of the bullion from the imported thread would find its way to the mint for coining, as well as to prevent the domestic manufacture of the thread being used as means to smuggle bullion out. Indeed, the patentees promised to import at least £5,000 of bullion every year, rather than to use bullion already in the country that might otherwise end up at the mint.

The project became all the more important in the late 1610s, however, as the various states, cities, and princelings of Germany geared up for the Thirty Years War. These principalities began to debase their silver currencies, and the German mints thus sucked the silver out of England. Soon, hardly any silver was being coined by the English mint at all. And to make matters worse, the resulting inflation in Germany also seems to have made it harder to sell English exports there too, leading to a worsening of the English balance of payments .12 Going into the 1620s, England experienced a painful shortage of cash.

And so the remit and powers of the gold and silver thread monopoly were expanded yet again. Dissatisfied with the performance of the patentees, in 1618 the king took the matter into his own hands. He effectively nationalised the gold and silver thread industry, creating a “commission” to oversee all production and imports of the stuff. The commissioners continued to face too much resistance from the London goldsmiths, however, so he soon brought in a highly competent bureaucrat to make it work. This was, of course, Sir Giles Mompesson, who like with the business of licensing inns, was to prove too effective for his own good.

And it was at this stage that the commission became a more wide-ranging financial regulator. Mompesson — who was merely a salaried bureaucrat for the commission, rather than taking a cut of the profits — was soon affecting essentially everyone who used bullion in London, making the refiners, thread-makers, silk-workers, button-makers and haberdashers all sign up to contracts with severe financial penalties if they didn’t keep meticulous records of where they sourced and sold their bullion.13 Those who refused, he punished.

So in 1621, when Parliament began to investigate Mompesson for his part in creating a centralised bureaucracy for licensing inns, it also turned its attention to gold and silver thread. Although he had had absolutely no part in starting the project, and merely in making it effective, hostile MPs soon made him out to be a villain who was erecting a new and upstart court of justice — a new way to oppress the people. Worse, MPs started to paint the gold and silver patent monopoly (conveniently ignoring the fact that it had since become a royal commission) as being to blame for the financial problems it aimed to suppress.

They argued that its control of gold and silver thread imports had stifled a valuable source of imported bullion, and that the thread they were producing was actually being made with melted-down English coin. It was almost immediately condemned — especially by MPs who just so happened to be prominent members of the Goldsmiths’ Company14 — as a major source of the country’s economic woes. When the leading MPs started to look into precedents of how Parliament might be able to punish monopolists, and actively compared him to historical figures who had been hung for treason, Mompesson knew that nothing he could say in his defence would ever work. He managed to escape custody and fled the country.

And in so doing, inadvertently set in stone how patents for invention would be regulated for the next few hundred years. More on that soon.

Marian Campbell, ‘Gold, Silver and Precious Stones’, in English Medieval Industries: Craftsmen, Techniques, Products, ed. John Blair and Nigel Ramsay (The Hambledon Press, 1991), p.134

Jonathan Harris, ‘Two Byzantine Craftsmen in Fifteenth-Century London’, Journal of Medieval History 21, no. 4 (1 December 1995): 387–403

e.g. James Spedding, ed. The Letters and the Life of Francis Bacon, Vol. IV (Longmans, Green, Reader, and Dyer, 1868), pp.259

Nicholas Mayhew, Sterling: The History of a Currency (John Wiley & Sons, 2000), p.104

Ibid., p.65

B. E. Supple, ‘Currency and Commerce in the Early Seventeenth Century’, The Economic History Review 10, no. 2 (1957), p.240.

Mayhew, p.64

James Spedding, ed. The Letters and the Life of Francis Bacon, Vol. IV (Longmans, Green, Reader, and Dyer, 1868), pp.256-58

Mayhew, p.84-5

Tricia Nguyen, ‘Scandal and Imprisonment: Gold Spinners of 17th Century England’, Hidden Stories/Human Lives: Proceedings of the Textile Society of America 17th Biennial Symposium, October 15-17, 2020, 1 October 2020.

Janelle Day Jenstad, ‘Public Glory, Private Gilt: The Goldsmiths’ Company and the Spectacle of Punishment’, in Institutional Culture in Early Modern Society, ed. Anne Goldgar and Robert Frost, vol. 20, Cultures, Beliefs and Traditions: Medieval and Early Modern Peoples (BRILL, 2004), 203.

J. D. Gould, ‘The Trade Depression of the Early 1620’s’, The Economic History Review 7, no. 1 (1954): 81–90

Wallace Notestein, Frances Helen Relf, and Hartley Simpson, eds., Commons Debates, 1621, vol. VI (Yale University Press, 1935), p.33 has a pithy list of the interest groups who complained.

William Herrick in particular, if you’re interested.

I suppose the point of swapping a chunk of bullion for coins was that coins are more liquid - you could settle a bill of any size for enough coins while trying to pay someone with a lump of bullion would be trouble. As such, the seignorage charge is something like a central bank overnight interest rate - the price of liquidity from the provider of last resort.

It was somewhat of an aside, but the statistic that jumped out at me was "At a time when bread and beer made up 75-85% of the typical person’s expenditure..." Is there some index/resource that lists what percentage of a person's income certain goods consume? I'm able to find indices for the twentieth century but I don't know where to look for data for the 19th century and earlier.