Age of Invention: Parliament Rift

Legalised theft, noble orphans, and a king's quest for cash

You’re reading Age of Invention, a newsletter on the causes of the British Industrial Revolution and the history of innovation. This free edition went out to over 7,200 people. You can sign up here:

This post is effectively the fifth instalment in an ongoing series on the evolution of early patents. In it, we’re going to look at how James I wanted to modernise the English state, trying to rid himself of some unpopular feudal privileges in exchange for cash. We’ll delve into some of the details of medieval Crown finances, and look at how a seemingly small error meant that his attempts at reform failed. There won’t be much mention of monopolies this time, but you’ll start to notice the reappearance of some cast members… Here are Parts I, II, III and IV if you need to catch up.

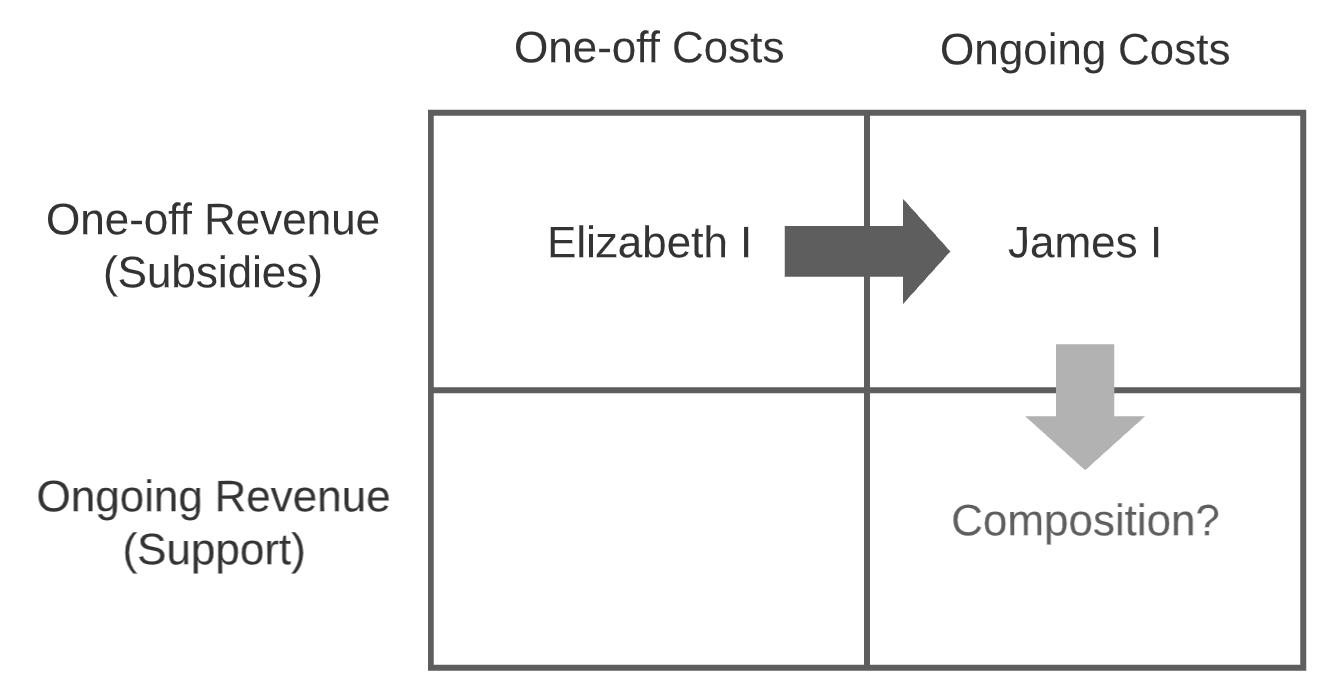

As we saw last time, England in 1603 welcomed a new monarch — James Stuart of Scotland. He showered his new subjects with titles and gifts, to reward and buy their support. But after a generous honeymoon period of about a year, he and his government soon discovered that they were leaking cash. Despite eliminating the costly wars in Spain and in Ireland, James still had to pay off the debts that his predecessor Elizabeth I had incurred in fighting them. And he had a more extensive, and expensive, royal family to support. He traded the one-off expenses of war for the ongoing expenses of a profligate court.

This may sound like a good deal. James effectively stopped the English Crown splashing out money on really big but infrequent expenses, while increasing its ongoing expenditure — like refraining from buying a new car every few years, while spending a lot more each month eating out at restaurants.

But the Crown’s sources of revenue were ill-suited to this change. The funding for wars had been voted to Elizabeth by Parliament, usually as and when the need arose. Such expenditures were matters of national interest, and she otherwise just relied on other sources of income — ongoing taxes like customs duties, or simply the rent from her lands. When the one-off “subsidies” granted to her by Parliament had not quite been sufficient to cover the costs of the wars, Elizabeth had made up the difference by keeping her own ongoing expenses as low as possible, and took out loans to fill any gaps. It also helped that in the years before crises, Elizabeth had tried to run a surplus, building up a war-chest of cash to dip into.

So switching to the new pattern of expenditure was not straightforward. To increase the Crown’s ongoing expenses, it would have to find more sources of ongoing income, especially as it was already in deficit and had loans to pay off. It was politically impossible for James to ask Parliament for extra one-off subsidies to help him bridge the gap, as some of Elizabeth’s subsidies from 1601 had yet to even be collected. He did actually test the waters about what would happen if he did ask, just in case, but when the matter was raised by some would-be sycophants, it was met with outrage. As one member of Parliament angrily put it, “we have no sheep that yields two fleeces in the year.”1

The country was already feeling over-taxed, there were no looming crises to justify such extra taxation, and even if there were, such one-off measures would be unsustainable. James needed to find revenue streams to match his spending leak — and ideally, to even exceed it. His ministers fretted about getting the Crown back into surplus again, to build up another war-chest. Who knew when the next war or rebellion might arise.

So when James called his first Parliament in 1604, it was not really to ask for one-off subsidies as Elizabeth had so often done. Instead, he and his ministers focused on outlining a series of financial deals. (Rather than using the term deal, at the time they called it “compounding”, to reach a “composition”.)

The basis of the deals was to take many of the monarch’s feudal privileges and prerogative rights, and to agree to abolish them in exchange for regular payments. Rather than having to call Parliaments to raise extraordinary taxes, or “subsidies”, James wanted to establish taxes that were both ongoing and ordinary — what came to be known as “support”. He and his ministers began to consider which privileges he ought to give up, initially choosing those that were the most unpopular. They must have reasoned that Parliament would pay especially well to eliminate them.

One of the privileges, known as purveyance, was the right of the Crown to purchase provisions for the royal household at below market rates. It was, in other words, a kind of traditional theft, with people being forced to sell food, fuel, and other goods to the court, at prices that they weren’t even allowed to choose. In theory, the king’s purveyors had set prices and quantities that they were supposed to use. But theory was not the same as practice. Corrupt purveyors demanded illegally low prices, seized more goods than necessary, requisitioned people’s carts, and pocketed the proceeds for themselves. Although various laws already regulated purveyance, the abuses multiplied — especially with James’s lavish entertainments during his journey south, at his coronation, and now more permanently because of his much larger court.2

The other important unpopular privilege was wardship, a practice hated by even the highest of lords. This concerned the children of the tenants-in-chief — those who in the ancient feudal hierarchy held their land directly from the Crown. Essentially, when a tenant-in-chief died before their heir had come of age, the king became the guardian of the child. This may sound a little obscure, or even trivial, but it was not. Wardship essentially gave the king control over the noble children’s lands, incomes, and even persons — control that the Court of Wards, which administered the system on the Crown’s behalf, could effectively sell to the highest bidders. The Master of Wards was an especially lucrative and coveted post. Those who purchased the rights to a wardship effectively got to use the wards’ property as their own, with all the opportunity for corruption that that entailed. They could even arrange for the wards to marry their own children, securing the inheritances for themselves. Buying a wardship was like buying the right to become a fairy-tale evil stepmother. Many in Parliament will have known miserable childhoods and marriages as a result.

Yet for all the unpopularity of these feudal dues, the deal continually failed to materialise — probably because James had inadvertently shot himself in the foot.

Thanks to his overwhelming generosity when he became king, James had actually weakened his hold over the House of Commons: by promoting the most experienced and effective ministers to peerages, they had to sit in the House of Lords instead. It was an especially big mistake to lose the Commons-wrangling talents of his chief minister Robert Cecil. So Cecil and the rest of the Privy Council were forced to rely on relatively inexperienced and often unreliable proxies,3 while some of the most radical and vocal opponents of monarchical privileges gained control.

Indeed, they were sometimes one and the same. One of Cecil’s proxies in the Commons, Sir Robert Wroth, was actually one of the ringleaders of the anti-monopolists who had so vexed Cecil in the Parliament of 1601.4 Wroth was an old and principled opponent of purveyance, rather than a government operator seeking a deal for the Crown. As the Venetian ambassador put it in a report to his masters back home, “Parliament is full of seditious subjects, turbulent and bold, who talk freely and loudly about the independence and the authority of Parliament in virtue of its ancient privileges”.5

Without being there to keep an eye on things, Commons discussions of purveyance and wardship went well beyond what Cecil had intended. And opening up the topics allowed the radicals to set the agenda, with a bill to restrict purveyance being introduced by the lawyer Lawrence Hyde — the very same person who had introduced a bill in 1601 to try to limit Elizabeth I’s use of patent monopolies, as discussed in Part II. Hyde then formed a small parliamentary committee on purveyance, which was dominated by other radicals — including one Nicholas Fuller, who had been a shockingly outspoken critic of the royal prerogative in the Case of Monopolies, as discussed in Part III. (We shall meet Fuller again, for over the course of the 1600s he became something like a modern-day Leader of the Opposition.6)

With the members of the Privy Council mainly in the House of Lords, the negotiations over composition largely took place between delegations from the Commons and the Lords. In effect, “the Lords” in 1604 became synonymous with the Privy Council — the king’s ministers — while the power vacuum in the Commons made it all the more independent and outspoken than ever. It began to create a rift between the two houses, especially as the Commons could not reach a consensus on the amounts for the deals. When the Lords proposed £50,000 a year to abolish purveyance, this was far too high for the Commons. They wanted to pay less than half that amount. When the Commons proposed £30,000 a year to abolish wardship, this was far too low for the Lords. They wanted more than double.7

Finally, to make matters worse, once the matter of purveyance had been openly debated, it could not then be dropped. The likes of Hyde and Fuller fervently believed that in practice it had become openly illegal, and they would not now back down. Devoid of a deal, the king’s debts continued to pile up, and he began to search for more controversial means to boost his income. As we’ll see next time, over the next six years he would test, to breaking point, the relationship between Commons and Crown.

Thank you for reading! If you’d like to support this work you can become a paid subscriber. It means getting extra “director’s cut” kind of posts in intervening weeks, as well as allowing me to do what I do. You can sign up here:

'House of Commons Journal Volume 1: 19 June 1604 (2nd scribe)', in Journal of the House of Commons: Volume 1, 1547-1629 (London, 1802), British History Online

There are plenty of overviews of the system, but this one is especially thorough: Louis Martin Sears, ‘Purveyance in England under Elizabeth’, Journal of Political Economy 24, no. 8 (1916): 755–74.

Incidentally, Sir Francis Bacon in 1604-6 appears to have been the de facto representative of the government in the Commons. He was talented, but with so many other issues to deal with, on matters of religion and the proposed union of Scotland and England, those talents were stretched too thin. There’s a great overview of the issue of managing the Commons here.

Pauline Croft, ‘Parliament, Purveyance and the City of London 1589-1608’, Parliamentary History 4 (1985), p.13; Pauline Croft, ‘Wardship in the Parliament of 1604’, Parliamentary History 2 (1983), p.42

'Venice: May 1604', in Calendar of State Papers Relating To English Affairs in the Archives of Venice, Volume 10, 1603-1607, ed. Horatio F Brown (London, 1900), pp. 148-154. British History Online

Stephen Wright, ‘Nicholas Fuller and the Liberties of the Subject’, Parliamentary History 25, no. 2 (2006), p.181

Croft, ‘Wardship’, p.43 for the figure of £30,000 per year for wardship suggested by the Commons, with the retort of £80,000 per year thought reasonable in a memorandum by the clerk of the Court of Wards, to Cecil; Croft, ‘Parliament’, p.16 for the £50,000 per year asked for by the Lords for purveyance, with the £20,000 per year plus a subsidy that some in the Commons thought more reasonable.