Age of Invention: The Second Soul, Part II

The Lands that Salt Forgot

You’re reading Age of Invention, my newsletter on the causes of the British Industrial Revolution and the history of innovation, which goes out to over 30,000 people. This is the second instalment of this year’s special, monthly series on unsung materials. To stay tuned, subscribe here:

In last month’s post I introduced the importance of salt. It was a major input to agriculture, and was widely used for preserving food, staving off the corruption of animal matter as though it had entered into corpses like a “second soul”. It was, in fact, a basic necessity of life, which made it an ideal revenue-raiser for kingdoms, empires and republics all over the world. The geography of salt sources, as we saw, may even have defined the contours of many states.

It’s difficult to appreciate salt’s historical significance, however, because it’s now so extraordinarily abundant.

People used to worry about salt supplies as a matter of survival, or at the very least of staving off economic catastrophe. Without salt, a population would become weaker, more prone to disease, and ultimately die. And even if enough salt made it directly onto people’s dinner tables, it would spell food shortages. Without enough salt, no fish, meat, butter or cheese might ever make it to market, while livestock would be thinner and yield less meat. Draught animals would weaken too, becoming less able to pull ploughs or transport things. All of the basic foundations of the economy, overwhelmingly reliant on agriculture, would be undermined. Any further use for salt was a nice-to-have, only made possible if it was especially abundant — even in major industries like agriculture. Francis Bacon in the 1620s remarked how salt could in some cases be useful as a fertiliser for grain, but had to admit that it was “too costly” to do so at scale.1

Today, however, the vast majority of salt is used as an input to produce chemicals for industry, with a mere 12% used for preparing or preserving food. Indeed, we produce so much salt today that the second most common use of it worldwide is to merely dump it onto the roads of some countries merely to keep them from getting icy for part of the year. Salt became so abundant over the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries that the main problem increasingly became how to find a use for it all. British salt, for example, came to be exported all over the world in the nineteenth century, but by 1888 almost all the country’s salt producers had to merge into a single company, the Salt Union, closing down various saltworks to try to restrict production and restore the industry to profitability. This failed, however, and despite the rise of new demand for salt in the chemical industries, in water softeners, and for de-icing roads, the huge salt-making plants established in Britain in the 1970s and 80s have still never had a chance to operate at full capacity.2

To what do we owe this saline superabundance? To understand, we first need to look at the four major ways to get salt.

If you had access to the coast, you could evaporate it from seawater, though this is only about 3.5% salt. The process involved a lot of dry, sunny weather, or else required a lot of fuel to burn. Or, you could try a technique called sleeching: where there were especially flat coastlines, the sea at its highest, twice-monthly spring tide would have an especially long range, soaking plenty of coastal sand, silt or mud with its brine. In the two weeks until the spring tide returned, provided the weather was dry enough, the surface of this salt-encrusted sand, silt or mud could then be scraped away and have water poured through it to yield a much stronger brine ready for boiling. What sleeching might save in fuel, however, it more than made up for by requiring a lot more land and hugely more labour — as well as still leaving you at the mercy of the weather.

If you were too far from the coast, you had to rely on an inland source. If you were lucky, you might find a briny inland spring or lake that had been enriched by salt deposited millions of years ago underground. The brine of an inland salt spring could be much stronger than seawater, requiring a lot less fuel or sun to evaporate the water away. The salt springs at Northwich and Nantwich in Cheshire, in the northwest of England, were about 16% salt - over five times stronger than seawater. Those at Middlewich nearby, and at Upwich in Worcestershire, could be as high as 25% salt. Obtaining a given quantity of salt from such brine, when compared to ordinary seawater, could require just a ninth of the time and fuel.

Heavy rains, however, or flooding from nearby lakes and rivers, could threaten to dilute such sources. Control of the Sambhar salt lake in north-western India, for example, had allowed the allied Rajput kingdoms of Amber and Marwar, later known as Jaipur and Jodhpur, to throw off the Mughal Empire in the early eighteenth century, and with the spread of the railways in the late nineteenth century the lake would become the entire subcontinent’s chief source of salt. But although in a good year in the 1880s it could produce over 250,000 tons of the stuff, in a bad year, thanks to a floods or monsoons, this could plummet to just 14,000 or even just 3,000 tons — a drop in output of 94-98%.3

Finally, if you were especially lucky, you might find the underground deposits that enriched such springs, and mine the salt as a rock. Although this might require a bit of fuel and water to refine it, dissolving it and evaporating it again to remove dirt and impurities, salt rock was the most energy-efficient salt source of all.

If you were unlucky, however, you might find yourself in a place where salt could not be made at all. We looked at a few of these in Part I, when I noted how salt-producing coastal areas could often come to dominate the salt-less places further inland — I mentioned, for example, how control of the salt-producing coasts meant control of the kingdom of France. There were fully inland examples too: how the Habsburg archdukes of Austria, with their salt springs at Altaussee, Hall-in-Tirol, Hallstatt, and Ischl, exerted control over the salt-less kingdom of Bohemia (more or less modern-day Czechia) — especially after 1706, when thanks to the Spanish War of Succession, they managed to exclude competing salt from the duchy of Bavaria.4 And even when such salt-forsaken places did not come under the rule of an especially monopolistic neighbouring salt-producer, their populations tended to suffer under heavy taxes on salt consumption, because rulers could more easily control and tax the salt that had to be imported.

Yet the most interesting places of all — one of which was to become the original catalyst for our current salt superabundance — were the kinds of places that had plenty of coastline but still struggled for salt.

Bengal Blues

Take Bengal, the bay region now split between Bangladesh and the north-eastern Indian province of West Bengal, where the rivers Ganges and Brahmaputra, having collected many other rivers along the way, all dump their waters, splitting the land into a labyrinthine delta. It might, on the face of it, be surprising that Bengal lacked salt. After all, the region is both warm and coastal. But it is also extremely humid, making it almost impossible to evaporate the seawater using the sun because the air is already so saturated, while the sheer quantity of fresh river water flowing out into the bay — especially during the rainier seasons, when those rivers swelled — meant that the salt in the bay’s seawater became all the more diluted. I mentioned above that on average water of the seas is about 3.5% salt. On the coast of Bengal, however, the surface water towards the coastline is just 2% in winter, falling to about 1% in the rainy summer. Closer to the river delta, from whence the brine was often actually taken, it can fall to under 0.5%. So not only was it not dry enough to make salt cheaply using the sun; you would often have needed perhaps three to seven times as much time and fuel as on other coastlines to extract a given quantity of salt.

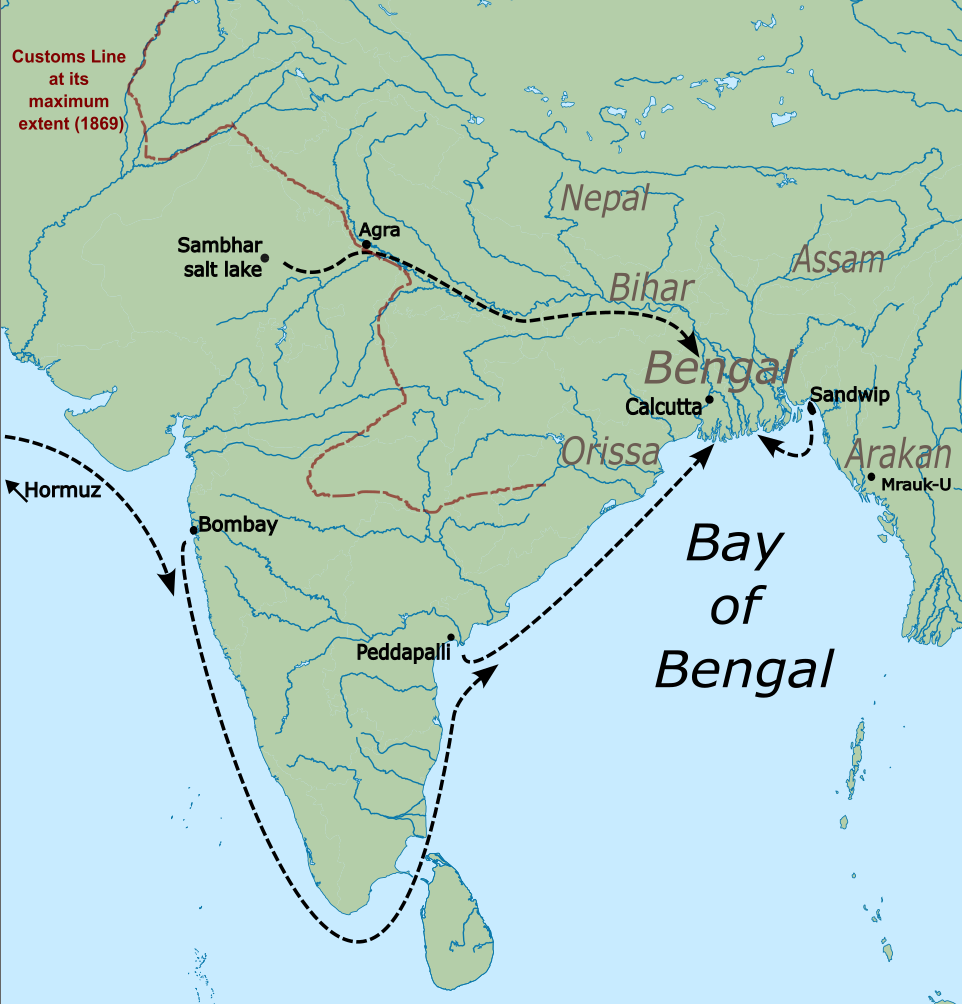

It was no wonder, then, that Bengal — an extremely densely-populated place, even back in the sixteenth and seventeenth century — needed to import vast quantities of salt. Visiting Europeans noted how salt from the Sambhar lake was amassed at the Mughal capital at Agra, where it was loaded every summer onto huge boats of some three, four, or even five hundred tons each, and sent 1,500 kilometres or so down the rain-swollen Ganges all the way to Bengal. Hauling the boats back up against the current, even in winter when it was less strong, took five times as long.5 And there was a large coastal trade too, with salt imported from the places further down the Bay of Bengal — a lot of sun-evaporated salt was produced at Peddapalli, for example, now the village of Nizampatnam6 — as well as from around India’s tip, on its drier western coast near Bombay. Bengal’s appetite for salt even stretched as far as the Middle East. Merchants from India’s western coast would sell their wares at the isle of Hormuz, at the entrance to the Persian Gulf, and there load up on the island’s rock salt “as ballast, and carry it to Bengal, where scarcity gives it a value.”7 The region’s demand for salt thus tied together an ocean-wide commerce.

There was, however, a source of salt that was closer to home: the small island of Sandwip, where by 1600 over two hundred ships each year were reputed to load up on salt destined for mainland.8 But this, sadly, was to be its peak. Sandwip’s struggles were to be a microcosm of the whole of Bengal’s painful next few centuries.

As the closest source for Bengal’s insatiable demand, Sandwip’s salt was a major source of revenue to whoever ruled it. But this made it too attractive a prize. Local lords, the Mughals, the Portuguese, and the Arakan kingdom of Mrauk-U, in modern-day Burma, all vied for control of Sandwip, making it an opportunist’s dream. In 1607 the island was even briefly ruled by an Afghan mercenary, who was then ousted by a Portuguese salt merchant named Sebastião Gonçalves Tibao, who turned it into a pirate kingdom. This lasted c.1609-16 before the Arakanese dislodged him with the help of yet another player in the region, the newly-arrived Dutch East India Company — who, in turn, would in 1645 also try to take Sandwip for themselves.9

The depredations and disruptions soon took a toll on Bengal. The Arakanese, Portuguese, Dutch, and various assorted pirates, raided its coast for slaves, and Sandwip became depopulated and disappeared from notice. Commerce as a whole in the bay declined due to the constant struggles for power, with many parts of the coast becoming overgrown by jungle as the population retreated further inland, ceasing to cultivate it for rice. Those who remained were of the lowest castes of all, who braved the dangerous animals of the jungle to cut trees and make salt. On the Bengalese coast, after decades of decline, and despite all the factors that made it so costly, a domestic salt industry emerged.

It’s easy to see how. Before 1600, Bengal’s thriving industries and flourishing commerce seem to have allowed it to purchase imported salt. As that declined, however, its ability to pay for such imports diminished, while the overall need to feed its large population remained as pressing as ever. Bengal’s population had to get its salt from somewhere no matter what, even as its economy shrank. At the same time, Bengal’s coastline became a lot more plentiful in empty space and abundant wood fuel, while labour remained plentiful, and perhaps got cheaper as the decline in commerce meant that workers were left with fewer better-paying alternatives. So, despite all of the natural factors that made salt-making in Bengal such a difficult proposition, by the 1670s it was forced to resort to the highly land- and labour-intensive practice of sleeching.10

The echoes of this decline, and of Bengal’s former wealth, were still there in the 1760s, on the eve of its conquest by the English East India Company. Archibald Keir, a Scottish soldier-turned-merchant and salt producer there described how:

The places where the salt is now made in Bengal are called the jungles or woods. These cover a large tract of country, most of which was formerly cultivated, and paid a very great revenue to the government, and that was not two hundred years ago. They are now, however, from the ravages of pirates, and ill conduct of rulers perhaps, become the habitations solely of tigers and wild beasts, except only at the season when the saltmakers go there to cut wood and boil their salt.

Keir estimated that 1760s Bengal had about 130,000 people engaged in the various aspects of salt-making every year, producing some 120,000 tons of salt. These workers had to live in the jungle, where they dug the salt-laden sludge, felled trees for fuel, and did the salt-boiling over the course of December, January or February right up until the middle of June, before disassembling the whole saltworks ahead of the monsoon season, and reassembling it all again when the next season began. Keir’s own salt-works, which accounted for an estimated tenth of Bengal’s overall salt production, required so much space that it took over a fortnight to visit them all by boat. Bengal still imported some salt, but only really tiny amounts for more specialised or luxury purposes. Otherwise it supplied itself, and seems to have even exported some salt to the places further inland, like Assam and Nepal, which lacked access to salt sources of their own.11

What’s especially striking is how long sleeching in Bengal persisted — for a period of over three hundred years, from the early seventeenth to the late nineteenth centuries. But then the economic and political upheavals also persisted, while the production and sale of salt became a lucrative source of revenue for its rulers — just as it had on Sandwip, and almost everywhere else in India and the wider world.12 In the 1670s the salt trade in Bengal seems to have been farmed out by the Mughals to an Indo-Portuguese merchant, one Nicolao de Parteca.13 By the 1760s it was under the control of one of Bengal’s richest and most influential men, the Armenian merchant prince Khoja Wajid.14 Once Bengal’s salt production became established, its rulers and chief magnates thus gained a vested interest in keeping it going, raising barriers to competition — a trend that continued, and even worsened, when it was taken over in the 1760s by the English East India Company.

In quite a few modern accounts of Bengal’s economic history, there are complaints that the EIC oversaw the decline and eventual disappearance of Bengal’s salt industry. It’s often framed as a case of purposeful de-industrialisation, as cheaper salt sources from elsewhere in India and from Britain itself drove the sector out of business.15 But while British involvement in salt production did have terrible consequences, the problem was the other way around. The very existence of Bengal’s salt-making industry was a symptom of its seventeenth- and eighteenth-century impoverishment, which was maintained and exacerbated by the perverse incentives faced by its rulers.

Imagine for a moment that a wealthy country today suffered a truly major, back-to-the-Dark-Ages kind of catastrophe — a zombie apocalypse, or a nuclear fallout or something — and people who had once been surgeons, engineers, restaurant chefs, management consultants and a whatnot, had to all resort to becoming farm labourers just to keep the population alive. This was the situation with Bengal and salt-making, though it did not require a catastrophe of such magnitude — a fall to subsistence back then was not so great or unfathomable a drop as it is today. So it makes little sense to frame the eventual decline of Bengalese salt-making due to the influx of cheap salt — largely thanks to railways, steamships, and so on — as a bad thing. It would be like complaining, when the world eventually recovered from its post-apocalyptic Dark Age, that back-breaking farm labour was disappearing because food could be produced more cheaply.

Making salt in Bengal was a downright horrible job, significantly worse than making it anywhere else in the world at the time, and possibly ever. This was back-breaking work for months away from home, chopping trees and gathering mud in swampy, malaria-infested jungle for next to no pay. The death-rate, from disease, drowning, and wild animals, was astonishingly high, at about 6% of workers per season. Tiger attacks alone seem to have been responsible for two thirds of the casualties, though employers suspected that some of these may actually have been disguised desertions. Yet even when concerted attempts were made in the 1790s to improve conditions, by paying bonuses to the foremen based on survival rates, and investing in better weapons, boats, and supplies, it was considered essentially impossible to ever reduce the death toll to even 2%.16 And that’s just per season, not per year. By comparison, the death rate among adult slaves working on a sugar plantation in Jamaica seems to have been about 0.3% per year.17 The most dangerous job in the United States today, which is logging, has a death rate of just 0.082% per year. There was a reason that salt-sleeching in Bengal was consigned to those of the very lowest castes, many of whom were coerced.

Indeed, the salt-workers were often trapped into a kind of hereditary debt slavery. Employers lent to the workers in advance of the salt-making season, so that they could start building their houses and sleeching works in the jungle, and begin cutting wood for fuel. But bad weather, flooding, or even wild animals often prevented the workers producing enough salt to ever pay them back. Failure one season left them bound to return to the jungle the next season, and the next, until the debt was made good. When salt-workers ran away from these obligations, or simply died, employers insisted that their families or even their neighbours were liable, with the debt passing on from generation to generation and throughout whole villages until it effectively became a kind of custom. Anyone who had ever worked at a saltworks was often liable to be conscripted again for the jungle, whether they were really indebted or not.18

The great fault of the British was not that they eventually let the Bengali salt-sleeching industry die away, but that they continued it, and even expanded it. The EIC’s conquest of Bengal effectively marked its transformation from a mere long-distance freight shipping company, albeit an often violent one, into a fully-fledged territorial state — one paid for by taking over its lucrative monopoly on salt. The very continuance of the monopoly very quickly created an unstoppable bureaucratic impulse to maximise revenue, and so over the following decades the salt prices paid by Bengalis inexorably rose.

Perhaps worst of all, the use of salt-sleeching was expanded. Many of the Company officials actually wanted to make things better for the salt-workers. The EIC Bengal Presidency’s Governor in the late 1780s, for example, the Earl Cornwallis, tried to ban the use of customary forced labour in the saltworks, saying he would even discontinue the manufacture should it prove impossible to do it without coercion. He boasted that the descendants of the salt-workers would “look back with gratitude to the period of their emancipation”. We’ve also seen the 1790s attempt to lower mortality rates, which was largely at the initiative of one particularly conscientious Company salt agent. And Colonel Robert Kyd, who established Calcutta’s botanical garden, in 1788 even experimented with setting up solar evaporation salt pans in Bengal (which inevitably failed).19

But all these good intentions were but feeble taps against the hard wall of state revenue-maximisation, which entailed keeping production costs low. Well into the nineteenth century, although some of the more conscientious officials did ensure that salt-workers ended up with more freedom and higher wages, coercion was in practice difficult to stamp out, and often admitted to be necessary if more salt was to be made in Bengal. Better-paying industries like indigo-making were suppressed, lest they enticed workers away from the salt-works.20

And when it came to suppressing competition from other parts of India, the Bengal Presidency went to truly extraordinary lengths. When the neighbouring inland province of Bihar was fully subjugated in 1781, its traditional supply of salt from the Sambhar lake was blocked and replaced by ramping up production in Bengal by about 32,000 tons per year.21 Indeed, salt production in Bengal rose from around 100,000 tons per year in the 1760s to a peak of some 230,000 tons by the early 1830s.22

When much cheaper solar-evaporated salt from the neighbouring province of Orissa kept on being smuggled into Bengal overland, the English in 1804 conquered it, placing it under the salt monopoly too. And when cheap solar salt still continued to be smuggled in from other parts of India, especially from the Sambhar lake, the EIC’s Bengal Presidency began establishing customs houses along its border so that any incoming salt could be taxed accordingly, to maintain the monopoly price. By the 1840s, these customs houses had developed into a fully-fledged Customs Line of bare, raised earth, which was heavily guarded and swept flat after each patrol, so that the footsteps of any smugglers they’d missed could be spotted. The Customs Line reached its final form, however, in the 1860s, when it became a vast, living barrier of thorny, impenetrable hedge, three to four metres high and two to four metres thick, interspersed where necessary with stone walls, and punctuated by over 1,700 crossing points staffed by some 12,000 customs officials, stretching over 3,700 kilometres down northern India’s middle.23 (See map, above.)

Such measures were necessary if the Bengal Presidency wished to maintain its revenues, however, when we consider just how cheaply and easily salt could be made elsewhere. By the 1820s, the vast quantities of salt made by cheap and easy solar evaporation on the western coast of India, near Bombay — an area that was also even ruled by the East India Company — was thought to be the cheapest salt in the entire world, and widely exported.24 The tragedy of the Bengal salt monopoly, right up until it was replaced by a much lower, India-wide excise tax on all salt in the 1870s, was that the suffering of the jungle-dwelling salt sleechers and the deprivation laid on the population were entirely needless — these were sufferings perpetrated by policy, continued and extended for the state and its servants alone.

Yet perhaps the biggest tragedy of all was the unseen one — of what a salt-deprived coastal region could have looked like in terms of how it and its neighbours might have developed. To appreciate this, and to start appreciating how our present superabundance of salt came about, we need to look north-west, to the Baltic.

Baltic Boost

What do the Bengal coast and the Baltic Sea have in common? They’re both remarkably lacking in salt. I mentioned before that on average the ocean is about 3.5% salt, while at the Bengal coast it can drop to below 2 or even 1%, depending on the season. But the Baltic is astonishingly fresh. Even out at sea it’s under 1% salt, while towards the coasts it’s more like 0.3% or lower. It’s so low in salt that in some places it can hardly be tasted,25 though I’d not recommend trying to drink it.

The Baltic is so fresh because it’s fed by a lot of strong rivers while being extremely shallow, with far more water exiting it than flowing in from the North Sea, and with the incoming saltwater dropping to well below the surface because it’s denser. Indeed, only about 9,000 years ago the Baltic was an entirely freshwater lake.

So although the Baltic has fairly decent weather conditions for making salt — it gets a decent bit of sunshine in the summer, and the weather is quite dry — there’s just hardly any salt to be extracted from its coastline in the first place. Compared to almost every other coastline in the world, it would have taken about twelve times as much time and fuel to produce a given quantity of salt.

As with Bengal then, there was a huge prize available to whoever could supply the Baltic countries — especially as it became increasingly populated over the course of the middle ages. There were a few small salt springs near the coast, such as at Kolberg (now Kołobrzeg) and Greifswald. But the Baltic’s main supply had to come from the salt springs of Lüneburg. By about 1200, about 50,000 tons of Lüneburg salt were being sent each year down the river Elbe to Hamburg, on the North Sea coast, from whence it could be shipped to the Baltic.26 One of its main customers there was the city of Lübeck, which was heavily involved in Baltic fishing, because it had access to a small salt spring at Oldesloe a little further upriver, giving it the advantage over any rivals in being able to preserve its catch.

Lübeck and Hamburg were, in many respects, natural rivals. Both had easy access to salt springs inland. Both had leveraged this advantage to dominate their region’s fishing — one in the Baltic, the other in the North Sea. Both were thus in competition for the markets for that fish. Yet they decided to choose cooperation instead, extending privileges to one another’s citizens in 1230, and signing a formal alliance in 1241 that was to last for hundreds of years, soon taking more and more trading cities into their coalition and creating the famous Hanseatic League.

One big reason for that alliance, and for its persistence, was that geography had given them a problem in common: the kingdom of Denmark, which entirely controlled the straits between the North and Baltic seas, particularly the shipping lane called Øresund, or the Sound. The Danish kings were thus able to choke off the trade between the seas at will, extorting toll fees whenever Hamburg hoped to sell fish into the Baltic, and whenever Lübeck hoped to buy salt from beyond it. The original Hamburg-Lübeck alliance thus focused on securing the overland route between the two cities, sharing the cost of keeping it free of brigands. By securing an alternative route, albeit still an extremely expensive one, they could at least somewhat mitigate the Danish stranglehold over the inter-sea trade.27

In the fourteenth century, however, the Danish problem became significantly more acute. At one point in the 1310s the extended Hanseatic League was in danger of falling apart, as Denmark tried to conquer some of its member-cities on the Pomeranian coast. Lübeck failed to heed the call to defend them, too afraid of Danish retaliation. The nascent League survived this test, but largely only because Denmark could not actually afford its expansionism and descended into anarchy, torn apart by its German creditors when the loans came due, with the League occasionally intervening to tip the scales in its favour. Nonetheless, by the 1360s Denmark had recovered and was again attempting to expand, harassing Hanseatic merchants who tried to cross the Sound.

This time, however, Lübeck was more ready. It had developed the overland route to Hamburg and Lüneburg much cheaper by making the Stecknitz River more navigable, allowing the salt to be transported by boat for some of the way — a strategic insurance policy, which significantly reducing the hit they’d take to trade by going to war with Denmark.28 And this time the League most certainly waged a war. It inflicted such a heavy defeat on the Danes that in the 1370 peace treaty the League was ceded control of the Sound’s fortifications for the next 15 years, along with two thirds of the toll revenues. In effect, it had wrested control of the inter-sea trade; the Hanseatic League had become a new great power in the region, and could throw its weight around in the Netherlands, Norway, Russia, and England too.

The Danish problem never quite went away, however. In the 1370s and 80s, thanks to the machinations of queen Margaret, Denmark became united with both Norway and Sweden, formally merging in 1397 into a pan-Scandinavian new force — the Kalmar Union — with a shared monarch and foreign policy, more able to resist Hanseatic influence.29 But Lübeck and Hamburg also made the effort to bolster the overland route that connected them: they each worked to acquire more direct control of the lands that it ran through, and in 1398 opened a canal to connect the Stecknitz to the Elbe, making the route fully navigable by boat — it seems to have been Europe’s first canal to connect two separate river valleys by going over a summit, making it the world’s second, after the 1280s upgrades to China’s Grand Canal. Thanks to this medieval engineering marvel, Lüneburg salt now had direct access to the Baltic Sea, without needing to go through the Sound.

The Stecknitz Canal would stand Lübeck and the Hanseatic League in good stead, allowing tens of thousands of tons of salt to enter the Baltic when the Sounds was blocked. When the Kalmar Union attempted to re-impose tolls on its merchants passing through the Sound in the 1420s, the League was again able to win the war — even after a series of early major setbacks.

But a looming, much larger threat to Hanseatic hegemony was emerging, as a new group hoped to make the most of the Baltic’s lack of salt. More on them, and the Golden Age they ushered in, next time, in Part III.

P.S.

If you or someone you know is aged 18-22 and is in the UK in late August, there’s a residential programme being run in Cambridge called the ‘Invisible College’ after the group who in the 1650s preceded the Royal Society. It’s being organised by my friends at Works in Progress magazine. I’ve designed the programme’s talks on economic history and the history of technology, but there will also be a lot by other experts on public policy and how science works too. If you know someone who might be interested, the details of how to apply are here.

If you’d like to support my work, please upgrade to a paid subscription here:

Francis Bacon, Sylva Sylvarum: or a naturall historie in ten centuries (1627), p.150

L. Gittins, ‘Salt, Salt Making, and the Rise of Cheshire’, Transactions of the Newcomen Society 75, no. 1 (January 2005), pp.139–59

Richard M. Dane, ‘The Manufacture of Salt in India’, Journal of the Royal Society of Arts 72, no. 3729 (1924), pp.402–18.

E. Schremmer, ‘Saltmining and the Salt-Trade: A State-Monopoly in the XVIth-XVIIth Centuries. A Case-Study in Public Enterprise and Development in Austria and the South German States’, Journal of European Economic History 8, no. 2 (Fall 1979), pp.291–312.

Peter Mundy, The travels of Peter Mundy in Europe and Asia, 1608-1667, Vol. II: Travels in Asia, 1628-1634, ed. Richard Carnac Temple, (Hakluyt Society, 1914), pp.87-88, who says boats of 3-400 tons. Also Thomas Bowrey, A Geographical Account of Countries Round the Bay of Bengal, 1669 to 1678, ed. Richard Carnac Temple (Hakluyt Society, 1903). Bowrey at Patna mentions the same large boats at Patna, which he says are called patelas (p.225), as well as boats of twenty to thirty oars headed to Dhaka in Bengal with salt (p.229). Also John Jourdain, The Journal of John Jourdain, 1608-17, ed. William Foster (Hakluyt Society, 1905), p.162, says boats of 4-500 tons, which is remarkably close to Mundy’s estimate. He estimated that over 10,000 tons of salt was sent each year from Agra to Bengal.

Bowrey, p.56

Pedro Teixeira, The Travels of Pedro Teixeira, tr. William F. Sinclair (Hakluyt Society, 1902), p.165, who adds: “For in all the lands thereabouts [Bengal] is no salt made, but in the isle of Sundiva [Sandwip] alone”.

Fr. du Jarric, Histoire des Chose plus Memorables, Volume III, Book VI, Ch.XXXII (1614), pp.847-8. Incidentally, a lot of works talk about Sandwip as though it supplied the whole of Bengal’s demand for salt. They all go back to this source, however, which seems to have been misunderstood. The phrasing is, to be fair, a little confusing, but it actually seems to say that Sandwip exported to “the whole of Bengal” in the sense of merely being an exporter of salt to all of the various regions of Bengal, not that it was Bengal’s sole supplier (which in any case is demonstrably untrue).

By far the best account of these complicated struggles is S. E. A. van Galen, ‘Arakan and Bengal : The Rise and Decline of the Mrauk U Kingdom (Burma) from the Fifteenth to the Seventeeth Century AD’ (PhD thesis, Leiden University, 2008), chapters 3-4.

For evidence of saltmaking on the coast of Bengal in the 1670s, see Streynsham Master, The Diaries of Streynsham Master, 1675-1680, Vol I, ed. Richard Carnac Temple (John Murray, 1911), p.321; and Bowrey, pp.199, 219-20, 225

Archibald Keir, Thoughts on the Affairs of Bengal (1772), pp.60-70. When the East India Company’s servants took over Bengal’s salt supply in 1765, Lord Clive estimated it at about 96,000 tons, which is not too far off. James Grant, ‘Analysis of the Finances of Bengal’ [1784], in Fifth Report from the Select Committee on the Affairs of the East India Company (Irish University Press, 1969), p.313, writing not long after a disastrous famine, estimated Bengal’s own consumption at about 80,000 tons, produced by 45,000 workers. It’s unclear if this figure refers to just the salt-boilers or all of the additional workers required for transportation and fuel-cutting, as Keir’s figure does, but Keir’s figures are likely more realistic considering he managed a huge saltworks himself. Grant’s estimate for production by the 1780s, including increased supply to inland regions like Assam, Nepal and Bihar, is 112,000 tons.

Bowrey, p.56-7 and p.225 in the 1670s at both Peddapalli and at Patna notes salt as a monopoly of the Mughal Emperor; Master, Vol I, p.321, also in the 1670s, notes it for the Bengalese coast.

Bowrey, Vol II, p.95; this is somewhat backed up by a Venetian traveller to the Bengali commercial capital of Hooghly in c.1660, who noted that its wealthiest inhabitants were Portuguese merchants, who “alone were allowed to deal in salt throughout the province of Bengal”, quoted from J. J. A. Campos, History of the Portuguese in Bengal (Butterworth & Co., 1919), p.151

Sushil Chaudhury, ‘Armenians in Bengal Trade and Politics in the 18th Century’, in Les Arméniens Dans Le Commerce Asiatique Au Début de l’ère Moderne, ed. Kéram Kévonian, Hors Collection (Paris: Éditions de la Maison des sciences de l’homme, 2007), pp.149–67

e.g. Indrajit Ray, Bengal Industries and the British Industrial Revolution (1757-1857) (Routledge, 2011), chapter 5

H. R. C. Wright, ‘Reforms in the Bengal Salt Monopoly, 1786-95’, Studies in Romanticism 1, no. 3 (1962), pp.129–53; also A. M. Serajuddin, ‘The Salt Monopoly of the East India Company’s Government in Bengal’, Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 21, no. 3 (1978), pp.304–22

M. Craton, ‘Death, Disease and Medicine on Jamaican Slave Plantations; the Example of Worthy Park, 1767-1838’, Histoire Sociale. Social History 9, no. 18 (1976), p.242 - in reaching this figure I’ve taken the adult working age to be 20-49, but adjusting this either way doesn’t much change the figure.

Serajuddin has a pretty detailed account of worker conditions under EIC management. Such practices seem to have been essentially unchanged from what came before. See, e.g. Keir, p.65 for the early 1760s, and even Bowrey p.199 for the 1670s. Bowrey calls the dry season for salt-making May-August, but this must surely just be a misunderstanding.

Wright gives full details.

See both Serajuddin and Wright, who ultimately concludes that things had not much changed for the workers by the 1850s

Grant, p.313

See footnote 11, above, for estimates of production in the 1760s. For a table of production figures from the 1780s onwards see Ray, p.137 - this is calculated in maunds, for which I’ve multiplied by 80 to convert into pounds (the conversion is often given as 80 or 82) and then divided by 2,000 to convert to tons, which seems to be how it was estimated in the late eighteenth century.

For full details, there’s an entire book about its development: Roy Moxham, The Great Hedge of India: The Search for the Living Barrier That Divided a People (Carroll & Graf Publishers Inc, 2001).

John Phipps, Guide to the Commerce of Bengal (1823), p.34

e.g. Richard Pococke, A Description of the East, and Some other Countries, Vol II, Part II (W. Bowyer, 1745), p.229 says that the water at Rostock is not salty at all, and that at Wismar he “could not perceive it”

Philippe Dollinger, The German Hansa, trans. D. S. Ault and S. H. Steinberg, The Emergence of International Business, 1200-1800 (Macmillan and Co Ltd, 1970), p.46

Ibid, p.226

Ibid., p.150-1

Queen Margaret actually achieved the Kalmar Union with Hanseatic help, and in exchange for offering them all sorts of privileges — her successor almost immediately turned against them, however.

I had no idea salt trade can be this exciting. Can't wait for part III.

Speaking of Cambridge, what do you think about the Economies Past project claims that "the shift from the primary to the secondary sector was from 1600-1700, not 1750-1850 as 100 years of scholarship has assumed. In fact, the share of the male labour force in the secondary sector (excluding mining) was flat during the Industrial Revolution.

A second major finding is that the tertiary sector was the most dynamic sector of employment during the Industrial Revolution period."

Fascinating story very well told.