You’re reading Age of Invention, my newsletter on the causes of the British Industrial Revolution and the history of innovation, which goes out to 28,000 people. This is the first instalment of this year’s special series on unsung materials. To stay tuned, subscribe here:

Here’s a riddle.

There was a product in the seventeenth century that was universally considered a necessity as important as grain and fuel. Controlling the source of this product was one of the first priorities for many a military campaign, and sometimes even a motivation for starting a war. Improvements to the preparation and uses of this product would have increased population size and would have had a general and noticeable impact on people’s living standards. And this product underwent dramatic changes in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, becoming an obsession for many inventors and industrialists, while seemingly not featuring in many estimates of historical economic output or growth at all.

The product is salt.

Making salt does not seem, at first glance, all that interesting as an industry. Even ninety years ago, when salt was proportionately a much larger industry in terms of employment, consumption, and economic output, the author of a book on the history salt-making noted how a friend had advised keeping the word salt out of the title, “for people won’t believe it can ever have been important”.1 The bestselling Salt: A World History by Mark Kurlansky, published over twenty years ago, actively leaned into the idea that salt was boring, becoming so popular because it created such a surprisingly compelling narrative around an article that most people consider commonplace. (Kurlansky, it turns out, is behind essentially all of those one-word titles on the seemingly prosaic: cod, milk, paper, and even oysters).

But salt used to be important in a way that’s almost impossible to fully appreciate today.

[Before we crack on: because this post is so long, and because of all the illustrations and references, there’s a high risk that this email may end up truncated for some people. If this happens, you can always read the post online by simply clicking here.]

Try to consider what life was like just a few hundred years ago, when food and drink alone accounted for 75-85% of the typical household’s spending — compared to just 10-15%, in much of the developed world today, and under 50% in all but a handful of even the very poorest countries. Anything that improved food and drink, even a little bit, was thus a very big deal. This might be said for all sorts of things — sugar, spices, herbs, new cooking methods — but salt was more like a general-purpose technology: something that enhances the natural flavours of all and any foods. Using salt, and using it well, is what makes all the difference to cooking, whether that’s judging the perfect amount for pasta water, or remembering to massage it into the turkey the night before Christmas. As chef Samin Nosrat puts it, “salt has a greater impact on flavour than any other ingredient. Learn to use it well, and food will taste good.” Or to quote the anonymous 1612 author of A Theological and Philosophical Treatise of the Nature and Goodness of Salt, salt is that which “gives all things their own true taste and perfect relish”. Salt is not just salty, like sugar is sweet or lemon is sour. Salt is the universal flavour enhancer, or as our 1612 author put it, “the seasoner of all things.”

Making food taste better was thus an especially big deal for people’s living standards, but I’ve never seen any attempt to chart salt’s historical effects on them. To put it in unsentimental economic terms, better access to salt effectively increased the productivity of agriculture — adding salt improved the eventual value of farmers’ and fishers’ produce — at a time when agriculture made up the vast majority of economic activity and employment. Before 1600, agriculture alone employed about two thirds of the English workforce, not to mention the millers, butchers, bakers, brewers and assorted others who transformed seeds into sustenance. Any improvements to the treatment or processing of food and drink would have been hugely significant — something difficult to fathom when agriculture accounts for barely 1% of economic activity in most developed economies today. (Where are all the innovative bakers in our history books?! They existed, but have been largely forgotten.)

And so far we’ve only mentioned salt’s direct effects on the tongue. It also increased the efficiency of agriculture by making food last longer. Properly salted flesh and fish could last for many months, sometimes even years. Salting reduced food waste — again consider just how much bigger a deal this used to be — and extended the range at which food could be transported, providing a whole host of other advantages. Salted provisions allowed sailors to cross oceans, cities to outlast sieges, and armies to go on longer campaigns. Salt’s preservative properties bordered on the necromantic: “it delivers dead bodies from corruption, and as a second soul enters into them and preserves them … from putrefaction, as the soul did when they were alive.”2

Because of salt’s preservative properties, many believed that salt had a crucial connection with life itself. The fluids associated with life — blood, sweat and tears — are all salty. And nowhere seemed to be more teeming with life as the open ocean. At a time when many believed in the spontaneous generation of many animals from inanimate matter, like mice from wheat or maggots from meat, this seemed a more convincing point. No house was said to generate as many rats as a ship passing over the salty sea, while no ship was said to have more rats than one whose cargo was salt.3 Salt seemed to have a kind of multiplying effect on life: something that could be applied not only to seasoning and preserving food, but to growing it.

Livestock, for example, were often fed salt: in Poland, thanks to the Wieliczka salt mines, great stones of salt lay all through the streets of Krakow and the surrounding villages so that “the cattle, passing to and fro, lick of those salt-stones”.4 Cheshire in north-west England, with salt springs at Nantwich, Middlewich and Northwich, has been known for at least half a millennium for its cheese: salt was an essential dietary supplement for the milch cows, also making it (less famously) one of the major production centres for England’s butter, too. In 1790s Bengal, where the East India Company monopolised salt and thereby suppressed its supply, one of the company’s own officials commented on the major effect this had on the region’s agricultural output: “I know nothing in which the rural economy of this country appears more defective than in the care and breed of cattle destined for tillage. Were the people able to give them a proper quantity of salt, they would … probably acquire greater strength and a larger size.”5 And to anyone keeping pigeons, great lumps of baked salt were placed in dovecotes to attract them and keep them coming back, while the dung of salt-eating pigeons, chickens, and other kept birds were considered excellent fertilisers.6

Indeed, salt had been used since ancient times as a fertiliser. Contrary to popular belief, when the Romans allegedly destroyed Carthage and salted the earth, such practices in the ancient world were not about rendering the land infertile by making it too saline for anything to grow. You’d need an impossibly large amount of salt to do that. There’s no evidence Carthage was sown with salt at all, but the chosen ancient method of ruining farmland — seemingly practised by Ashurbanipal in the subjugation of Elam, for example — was to sow salt with the seeds of particularly aggressive weeds. Salt was sown not because it sterilised, but the opposite — because it could be so remarkably fructifying.

(While we’re on myths about the Romans and salt: there is an oft-repeated notion that “salary”, from the Latin salarium, comes from Roman soldiers being occasionally paid in salt. This, too, appears to be completely made up — yet another zombie myth to add to the growing list.)

The use of salt for growing crops went back to ancient times — it was recommended in Mesopotamia for growing date palms, for example — and this continued into the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Salt-rich sea sand was a widely-used fertiliser in the south-west of England, and the soil that had soaked up the runoff from the Cheshire brine springs was famous for its bounty.7 Where salty soils were less easy to get to, seeds could also be steeped in a brine made from common salt before they were sown, allegedly fortifying them against various pests and diseases.8 Exactly how effective and widespread was salt in agriculture, and were there periods where it was more in use? It’s unclear, because as far as I can tell nobody has tried to quantify it.

But regardless of whether it was used in agriculture, for preservation, or for cooking, salt was also essential. The human body is constantly losing salt through sweat, and to a certain extent urine, but it tries to keep the blood’s salt concentrations maintained at a certain level. So as the blood loses salt, the body also ejects water to adjust. Ironically, as you lose salt your body responds by drying you out. Without constantly replacing the salt in your body — which is only ever stored for a couple of days at a time — you will at first feel fatigued and a little breathless, but increasingly weak and debilitated, as though sapped of all energy. The slightest exertion would start to bring on cramps, then problems with your heart and lungs, as your body continually shed water. If these did not kill you — and they probably would — you would essentially die through desiccation. The process would be all the faster if you became ill, rendering even the slightest dehydrating fever or bout of diarrhoea utterly lethal.9

A population deprived of salt was thus one that was weaker and more prone to disease — and at a time when the vast majority of the economy’s energy supply came from the straining of muscle, both human and animal, that weakness in effect meant a severe energy shortage. Although the main fuels for muscle power were carb-heavy grains like wheat, rye, oats, and rice, the indispensable ingredient to getting the most out of these grains was salt — just as how nuclear power uses uranium as its fuel, but also requires a suitable neutron moderator. A population deprived of salt would quite literally be more lethargic and sluggish, making it less productive and poorer too.

Salt’s unique properties made it a serious tool of state. In 1633 king Charles I’s newly-appointed Lord Deputy for Ireland, Baron Wentworth, advised controlling its salt supply as a way to make the Irish utterly economically dependent on England. Given salt was “that which preserves and gives value to all their native staple commodities” — herrings, butter and beef — then “how can they depart from us without nakedness and beggary?” Salt would be a method of control, and a profitable one too, being “of so absolute necessity” that it could be sold to the Irish at inflated prices without much dampening demand: salt “must be had whether they will or no, and may at all times be raised in price”.10 Much like economists today, Wentworth saw revenue-raising potential in taxing goods with such unresponsive or ‘inelastic’ demand.

Wentworth’s scheme to control the Irish never came to be. But a great many other countries did choose to tax it. Given a minimum amount of salt had to be consumed by absolutely everyone, monopolising its sale — and levying what was effectively a tax by inflating the price well above the costs of importing or producing it — could function as kind of indirect poll tax, levied more or less per head of both people and livestock, but without any of the administrative hassle of taking and maintaining an accurate census in order to impose such a tax directly.

When compared to other necessities like grain, salt did not need to be traded in especially large quantities either, meaning that its supply could be monopolised with relative ease. And it could not be produced everywhere. Salt tended to be lacking the further you got from the sea coast, unless there happened to be some relatively rare inland sources like salt lakes, brine springs, or rock salt mines. And it could even be lacking on the sea coast where it was either too humid or too cold to get salt cheaply by evaporating seawater using the sun, or where there was insufficient fuel for boiling the brine. These places were thus prone to being charged inflated prices, while the states that controlled places where the costs of production were low — in warmer and drier climes where the salty water of coastal marshes could cheaply be evaporated using only the heat of the summer sun — could extract especially large monopoly profits from the difference. The revenue from controlling solar salt thus became the basis of many kingdoms, some unusually powerful republics, and even empires.

Empires of the Sun

The twelfth-century counts and viscounts of Toulouse and Provence, who ruled the salt marshes along the sunny French Mediterranean coast, discovered that a great many regions were dependent upon them for salt, including many of the lands up the river Rhône, towards Switzerland, and even down the coast towards the northern Italian cities of Genoa and Pisa. Alongside the customs duty these rulers charged on various other export goods — called gabelle, from the Arabic qabālah, meaning tax or tribute — the duties they charged on salt came to be the most important. It was, after all, something their customers could not live without. When much of Provence was unified in 1246 by Charles of Anjou, the youngest brother of king Louis IX of France, the region’s salt came to be more rigorously and systematically monopolised, with Charles taxing it within his own lands and demanding extortionate prices of many of his neighbours.

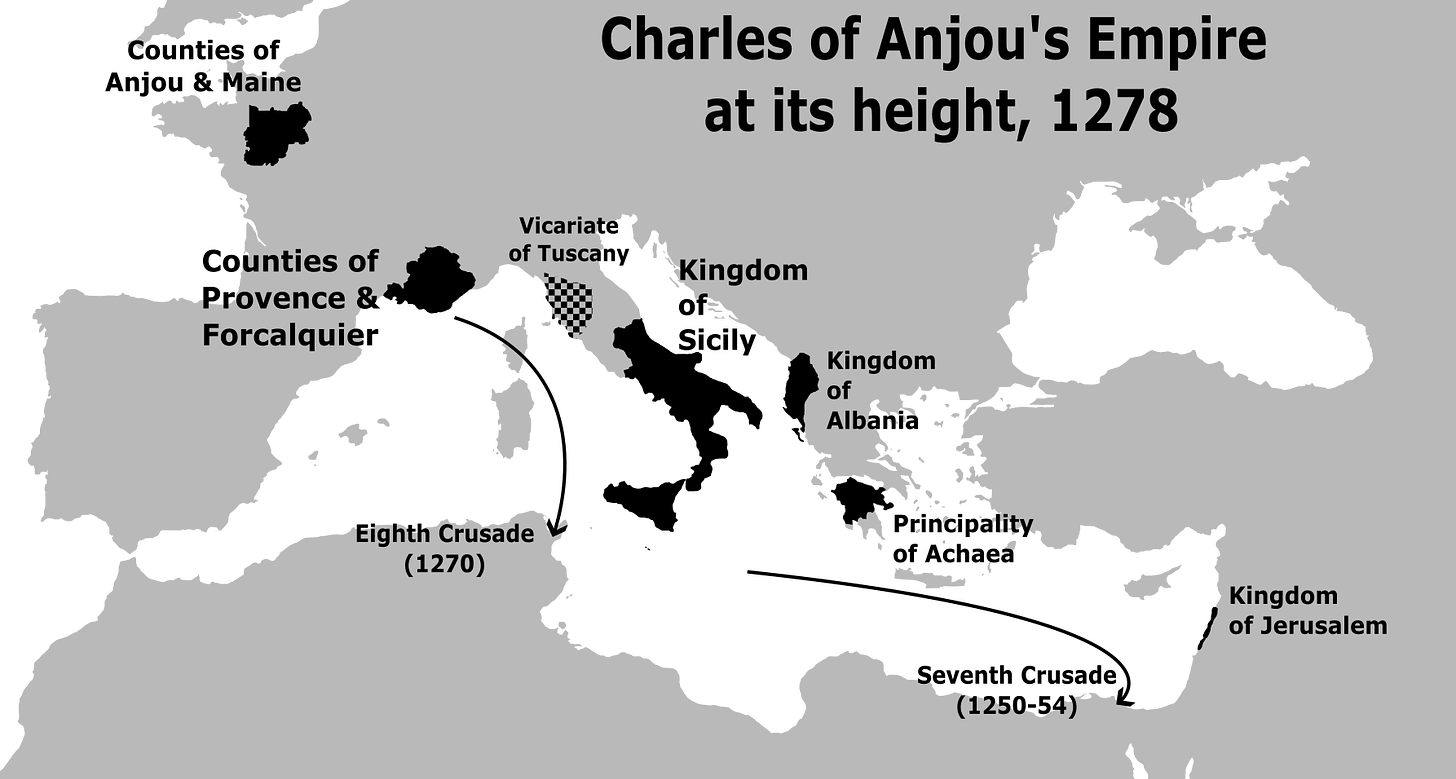

By the 1260s, Charles had so extensively exploited Provence’s production of salt that it alone accounted for almost as much revenue as all his other sources of income combined. Salt thus provided the war chest for him to project power into the Mediterranean: he conquered the kingdom of Sicily, including all of southern Italy; conquered much of Tuscany, which he effectively exchanged for the principality of Achaea in Greece; twice sent troops into central Italy to secure the elections of friendly Popes, John XXI and Martin IV; conquered Albania; purchased the sliver of what remained of the kingdom of Jerusalem; and joined his brother on crusades against Egypt and Tunis.11 Few have heard of it today, but Charles of Anjou created an empire based on salt.

On the other side of Italy the Republic of Venice — a city situated amidst a salty lagoon — used salt to exert its control over many of the territories further inland into north-eastern Italy. While Charles of Anjou was projecting his power into the Mediterranean, Venice continually went to war in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries to force these territories, eventually including cities like Verona, Vicenza, Padua, and Brescia, as well as much of modern-day Slovenia and Croatia, to buy their salt from it and it alone. At one point it even forced its salt on Milan.12 When Venice’s own salt lagoon eventually proved insufficient to meet the demand that it had enforced, the Republic then looked further afield for its salt supplies, offering high prices and substantial subsidies for ships importing it from across the Mediterranean — from North Africa, Ibiza, Sardinia, and especially the salt lakes of Cyprus, which became part of its empire — to make itself the region’s entrepôt for salt, while charging even higher prices to the populations it ruled.

The profits from Venice’s salt gabelle were fundamental to its military and financial might. By the end of the fifteenth century the proceeds accounted for about 15% of the Republic’s overall revenue. This does not sound like much, but the figure masks its true importance: the income from salt was more or less the only revenue that accrued directly to Venice itself, rather than being collected and immediately re-spent in the territories that the Republic ruled over. Sourcing and selling the salt, as well as enforcing the monopoly, was sub-contracted out to wealthy merchants — a process called tax farming — who in return for management of the monopoly paid the Republic a substantial but regular annual fee. Farming out the salt monopoly gave its revenue greater predictability, and for a few brief periods gave the Republic a kind of superpower that most other medieval states lacked: the ability to pay its debts. The revenues from Venice’s salt monopoly was often directed to paying the interest on loans, though fighting Genoa and Milan, followed by the rise of the Ottomans and France, eventually stretched it too far, costing the Republic its creditworthiness.13

The most infamous gabelle, however, was that of France. This seemingly owed its origins to a 1315 regulatory initiative in response to a salt shortage, to punish merchants who were allegedly hoarding the commodity. The king thus created a small bureaucracy of regulators with the powers to confiscate, stockpile, and then sell on the supposed hoarders’ salt. In the 1340s, however, the kingdom was plunged into crisis when Edward III of England invaded to claim the French crown as his own. Under intense pressure for cash, the salt regulation mutated, first with a 1342 gabelle levied on all salt exported, and in 1343 with the regulators’ powers of confiscation used to take the entire domestic salt supply into the crown’s hands as well. The salt was stockpiled into granaries by the officials and sold onto the French population at inflated prices. Following English victories and the need to stamp out marauding mercenaries and peasant revolts, the prices charged under the French gabelle became increasingly exorbitant.14 Yet salt was the thread by which the French king Charles V held onto his crown, helping him eventually claw some of his kingdom back from English occupation in the 1360s and 70s.

The French gabelle became exceptionally oppressive to the people who lived in the king’s core domains — a broad northern chunk of what is today France, centred on Paris, which came to be known as the pays de grande gabelle, or lands of the greater gabelle. Foreign visitors even remarked on the blandness of French bread there, devoid of salt.15 In this region the population were eventually made to purchase a minimum amount of salt for both themselves and their livestock from the granaries, making the gabelle’s resemblance to a poll tax all the more obvious. The major exception was a salt-producing region of Normandy, where a quarter of all the salt that was boiled was taxed at source rather than via the granaries — the quart-bouillon, which perhaps best translates as the quarter boilage.

Only as new regions came under direct control of the French king, clawed back from either English occupation or removed from the control of semi-independent nobles, was the gabelle extended to the rest of modern-day France. But this usually involved preferential treatment to ease the transition and keep them pacified. Much of southern France thus came to be the pays de petite gabelle, or lands of the lesser gabelle, being subjected to much lower salt taxes when they came under the French king’s rule. And some regions were exempted entirely, including some of the main salt-producing regions on the Bay of Biscay off France’s western coast. The duchy of Brittany, for example, didn’t have to pay the tax at all.

In the 1540s the king attempted to make the system fairer and more uniform by lowering the tax on salt in the lands of the greater gabelle, but raising it in the lesser-taxed salt-producing regions of southwestern France on the Bay of Biscay. Those regions, however, erupted into revolt, with Bordeaux even waving the English flag of St George as a symbol of its resistance.16 Eventually forced into submission, the regions agreed to pay the king huge one-off sums to free themselves of the gabelle forever, their representatives grovelling before the king with nooses symbolically worn around their necks.17 As a result of this buy-off, the regions came to be known as the pays rédimés, or redeemed lands. But salt seems to have become a lingering source of resentment and suspicion against royal centralisation, with some of these redeemed regions becoming hot-beds of French Protestantism.

When in the 1560s France descended into decades of periodic religious strife — its Wars of Religion — the contest was ultimately decided by fighting over control of the salt. Although the Catholic heartlands were those with the most onerous gabelle, where the consumption of salt was most heavily taxed, the Protestant rebels, called Huguenots, soon realised the value of controlling where that salt was being made. The two initial rounds of hostilities ended inconclusively, with both sides lacking the financial means for a protracted war. But when violence erupted for a third time in 1568, the Huguenots immediately rushed for control of the salt-producing western regions along the Bay of Biscay. Adopting the port of La Rochelle as their stronghold, they sold the next few months’ worth of the region’s salt production to the English for up-front cash and munitions.18

Using these salt-backed war loans turned out to be a winning strategy, with the Huguenots eventually forcing some concessions from the king despite a spate of battle losses — a strategy they repeated every time violence flared up again. Following the St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre of Huguenots in Paris, when in 1573 La Rochelle was besieged by the king’s Catholic forces, the Huguenots again sold the Bay’s salt to English merchants, helping them to resist wave upon wave of assault from a force at least five times their size, with the king losing between a third and a half of his army before he gave up and sued for a truce.19

And the Huguenots did it again in 1575 when that truce broke down.20 This time around they also captured the salt marshes on the Mediterranean, particularly at Aigues-Mortes. The move gave them even more salt to sell, this time to the merchants of Genoa, and allowed them to hold the entirety of south-eastern France hostage for its salt supply as well, denying the king a major source of revenue from the gabelle.21 The cash the Huguenots raised from the Aigues-Mortes salt allowed them to hire a force of German mercenaries who would prove decisive in the war. The king was forced to terms that were extremely favourable to the Huguenots — so favourable, in fact, that many French Catholics were radicalised, resulting in a widespread Catholic uprising that yet again plunged the country into conflict.

But in 1577 the Huguenots were on the verge of disaster, largely because they had lost the salt: the defection of an important leader in the south lost them the Mediterranean salt at Aigues-Mortes, and then they lost the town of Brouage, not far from La Rochelle, where three years’ worth of Bay salt had been stockpiled for sale to the English and Italians. The surrender of Brouage, just days before the arrival of reinforcements, was unpardonable to the Huguenot cause. The surrendered garrison, upon reaching La Rochelle, was reportedly punished using the ancient Roman method of decimation: one in ten of them, chosen at random, were executed. But the punishment was in vain. Having lost the salt, this time it was the Huguenots who were forced to the negotiating table.22

When religious strife erupted yet again in the 1580s, it was the Huguenot commander whose western power base gave the best access to the Bay of Biscay’s salt production — Henri of Navarre — who was able to fight his way, despite being outnumbered by his enemies, to become king Henri IV of France. Control of the salt ultimately meant control of France.

France may have been somewhat unusual, however, because of its geography. It had salt-producing areas on each of its coasts, but had an extensive interior with hardly any inland salt sources at all. Only in the 1670s, with the conquest of many of the lands to France’s east — Lorraine, Alsace, and the Free County of Burgundy — did it acquire a number of significant inland salt sources, and even then these were far from the main waterways running through the interior. Those waterways were crucial because a product as bulky as salt was otherwise exorbitantly expensive to transport overland. Thus, much of the population of France, along with the revenues of its state, could essentially be held hostage by whoever could control its salt-producing coasts and block the mouths of its major rivers — a fact appreciated by both its leaders and even its enemies.

In the 1620s, the French chief minister Cardinal Richelieu dreamt up an elegant solution to France’s salt-given predicament: to build a powerful navy, permanently remove La Rochelle’s defences, and extend the gabelle to all of the exempted or redeemed lands. The navy would help conquer La Rochelle, the defeat of the town would quash opposition to the gabelle, and extending the gabelle would help pay for both the navy and capturing the town.23

In the event, however, the English intervened, seemingly sensing the looming threat of a rival naval power: in 1627 they pre-emptively attacked the island of Ré, just off the coast of La Rochelle, hoping also to take the nearby island of Oléron, just off Brouage — both islands, if taken, would be perfectly placed to strangle France’s salt supplies, diminish its gabelle revenue, and permanently embolden Huguenot rebels. If the salt could be seized, the English hoped, the expedition might even pay for itself.24

The English invasion was an abject failure; La Rochelle fell to Richelieu’s forces; and the French navy expanded. The scene was set for the long reign of Louis XIV a generation later, whose epithet the “Sun King” would be fitting, his absolutist rule quite literally secured by the evaporation of seawater by the sun. But Richelieu’s plan did not quite come together fully: he never managed to extend the gabelle.

France’s geography perhaps made it a kingdom uniquely prone to being controlled in this way.

Compare with Spain, which not only had an extensive sunny sea coast, but plenty of inland salt sources as well. Spanish rulers did try to control and tax the production of salt, but the sheer number of potential salt sources made it difficult to enforce. Salt accounted for only about 6% of the crown of Castile’s revenue in the 1290s, and this figure was its peak. Despite repeated attempts to extract more, by the 1490s this had fallen to only about 3% of revenue and continued to fall.25 In 1564 the crown even seized the salt sources not already under its control, compulsorily “purchasing” them from various nobles, religious orders and towns, many of which were never actually paid in full, and imposed a French-style system of salt granaries that most people had to buy from.26 But even this drastic measure served only to restore salt’s importance to about 3% of revenue. There were simply too many potential sources of salt to be able to extract more, not only from the other Iberian realms like Navarre, Aragon and Portugal, but even from within Castile itself because of regional exemptions for places like the Basque coastal provinces. Smuggling and evasion were simply too rife to be able to extract more.27

Much the same problems beset the kingdom of Naples, which encompassed the island of Sicily and the whole southern Italian peninsula. Although it had no major inland sources, the country was practically made of sunny coast, at about 38.5 metres of coast per square kilometre of landmass compared to about 10 or so for Iberia or France. When Naples was ruled by Charles of Anjou, the archetypal salt monopolist, salt’s percentage contribution to the kingdom’s revenue in 1278 was only in the single digits.28 And in the 1440s, when the king of Naples required every household in the country to pay a certain amount for its salt, the revenues seem to have been disappointing.29 The costs of policing such a long sunny coastline were simply too great to yield much profit for the crown. (Even into the twentieth century, the Italian coast was said to be “most rigidly guarded by tens of thousands of coastguards and police to prevent any person whatsoever taking a cupful of water out of the sea”.)

At the other extreme, however, states with little or no coastline at all found it very easy to raise revenue from salt. For the landlocked duchy of Lorraine, the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries exports from its inland salt springs typically accounted for between half and two thirds of the state’s revenue.30 This even applied to landlocked states that did not actually produce any salt themselves. The dukes of the largely mountainous, Alpine region of Piedmont-Savoy imported almost all their salt via a tiny foothold of coast at the port of Nice — imports that they could control with relative ease, while clamping down on competing sources. There were only so many rivers and mountain passes through which to smuggle. As a result, despite producing no salt of their own, the dukes of Piedmont-Savoy’s chief source of revenue was a gabelle levied on their own population’s salt consumption. In the 1560s a proposed increase in the salt price was even commuted into an actual poll tax.31

Indeed, there is something unusual about the landlocked areas of much central Europe, which may help explain why the Holy Roman Empire had so many tiny sovereign states: it had a great many inland salt sources. I’ve not had a chance to look into it carefully just yet, but it’s striking how almost all the major players in the region — Austria, Bavaria, Saxony, the Palatinate of the Rhine, Lüneburg, Lorraine, Burgundy, and Brandenburg — each controlled salt sources of their own during their periods of greatest influence. Many bizarrely small sovereign states, too, like the Provostry of Berchtesgaden, seem to have maintained themselves by exporting salt. And the unusually wide dispersion of salt supply in inland Germany may also have helped maintain the sovereignty of tiny countries that didn’t produce any salt of their own — the Swiss cantons, for example, taxed consumption of salt that had to be imported, much like Piedmont-Savoy did, but their position meant they could often play the salt-selling Bavarians, Austrians, and French off against one another.

The geography of salt was thus a big deal, and may even have defined the contours of many early modern states. But there were social factors too. Although the demand for salt was highly inelastic, there were limits to how much oppression people would tolerate. There was a point at which they resorted to violence. France saw this every time it attempted to extend the gabelle into exempted regions — with the southwestern revolts that needed redeeming in the 1540s, as we’ve seen, as well as with a revolt in Normandy in 1639, and in Roussillon in the 1660s. In Spain, a 1632 attempt to regularise and extend the gabelle had to be dropped after widespread opposition. And in Piedmont-Savoy, an attempt in 1680 to extend the gabelle to the region of Mondovì, which had been exempted when it originally joined the duchy, sparked a violent revolt that took almost twenty years to finally stamp out. Most dramatically of all, in Russia the salt gabelle was such a major source of discontentment that the government became too afraid to raise salt prices. From a peak of about 15% of revenue being raised by the gabelle in the 1750s, by the 1790s salt prices were being held so artificially low that the gabelle’s revenue had gone negative — rather than taxing salt, the government found itself effectively subsidising it.32

Rise of the Rest

You might be starting to get an appreciation now for just how many places taxed salt — I’ve mentioned France, Spain, Poland, Russia, and various states of Germany and Italy. It was also a big earner for states in the Middle East, India, and China, with many of the same geographical factors applying to the success of salt taxes in exactly the same way. But it was not the empires of the sun, or even the wood-fuelled brine springs of inland states, that would reap the biggest rewards from salt.

It was, strangely, instead in the chilly, damp north-west of Europe, that the greatest gains were to be had. More on that in Part II.

If you’d like to support my work, please upgrade to a paid subscription here:

Edward Hughes, Studies in Administration and Finance 1558 - 1825, with Special Reference to the History of Salt Taxation in England (Manchester University Press, 1934), p.2

Anon., Theological and philosophical treatise of the nature and goodness of salt (1612), p.12

Blaise de Vigenère (trans. Edward Stephens), A Discovrse of Fire and Salt, discovering many secret mysteries, as well philosophical, as theological (1649), p.161

A relation, concerning the Sal-Gemme-Mines in Poland, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 5, 61 (July 1670), p.2001

Quoted in H. R. C. Wright, ‘Reforms in the Bengal Salt Monopoly, 1786-95’, Studies in Romanticism 1, no. 3 (1962), p.151

Gervase Markam, Markhams farwell to husbandry or, The inriching of all sorts of barren and sterill grounds in our kingdome (1620), p.22

e.g. John Collins, Salt and fishery, a discourse thereof (1682), pp.23-4, 28

e.g. Adolphus Speed, Adam out of Eden (1658), pp.105, 118, 136-7

Roy Moxham, ‘Salt Starvation in British India: Consequences of High Salt Taxation in Bengal Presidency, 1765 to 1878’, Economic and Political Weekly 36, no. 25 (2001): p.2270–74.

George O’Brien, The Economic History of Ireland in the Seventeenth Century (Maunsel and Company Limited, 1919), p.244, which has the transcription of Wentworth’s proposal

J. de Romefort, ‘L’ancêtre de La Gabelle: Le Monopole Du Sel de Charles d’Anjou’, Revue Historique de Droit Français et Étranger (1922-) 31 (1954): pp.263–69.

Patrizia Mainoni, ‘The Economy of Renaissance Milan’, in A Companion to Late Medieval and Early Modern Milan: The Distinctive Features of an Italian State (BRILL, 2014), p.123

Jean-Claude Hocquet, ‘Venice’, in The Rise of the Fiscal State in Europe c.1200–1815, ed. Richard Bonney (Oxford University Press, 1999), pp.381–415

Jean-Claude Hocquet, ‘L’impot Du Sel et l’etat’, in Le Roi, Le Marchand et Le Sel: Actes de La Table Ronde, L’Impôt Du Sel En Europe XIIIe–XVIIIe Siècle, ed. Jean-Claude Hocquet (Presses de l’Universitaires de Lille, 1987), pp.31-7

Ibid., p.33

Neil Murphy, ‘Henry VIII’s First Invasion of France: The Gascon Expedition of 1512’, The English Historical Review 130, no. 542 (2015), pp.55-6

'Spain: June 1543, 6-10', in Calendar of State Papers, Spain, Volume 6 Part 2, 1542-1543, ed. Pascual de Gayangos (London, 1895), pp. 363-385, no.151

Edward Hughes, ‘The English Monopoly of Salt in the Years 1563-71’, The English Historical Review 40, no. 159 (1925): pp.334–50.

"Cecil Papers: December 1597, 1-15," in Calendar of the Cecil Papers in Hatfield House: Volume 7, 1597, ed. R A Roberts (London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1899), 500-517: 1 December 1597 letter by Sir Henry Killigrew and Robert Beale to Sir Robert Cecil, noting La Rochelle’s failure to repay a 1573 salt loan to some London merchants. For the relative size of forces at the siege, see Kevin C. Robbins, City on the Ocean Sea: La Rochelle, 1530-1650: Urban Society, Religion, and Politics on the French Atlantic Frontier (BRILL, 2021), p.211, note 49

"Rome: February 1575," in Calendar of State Papers Relating To English Affairs in the Vatican Archives, Volume 2, 1572-1578, ed. J M Rigg (London: His Majesty's Stationery Office, 1926), pp.196-197.

"Cecil Papers: May 1575," in Calendar of the Cecil Papers in Hatfield House: Volume 2, 1572-1582, (London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1888), pp.96-99: see 29 May 1575 letter by Valentine Dale to William Cecil that “Aiguemortes and Beaucaire … are towns not to be parted with without good consideration, for by them they have the revenue of the salt in that country a good port in the Levant Sea [Mediterranean], and also a passage upon the river Rhone, a means of conveying the salt up into the country, and therefore the king strikes hard upon these towns”

The Huguenot leader, the future king Henri IV, sent word to the English of his victory at Brouage, in particular singling out the salt he had captured there. 'Elizabeth: August 1577, 21-25', in Calendar of State Papers Foreign: Elizabeth, Volume 12, 1577-78, ed. Arthur John Butler (London, 1901), pp. 89-115. See also: "Venice: August 1577," in Calendar of State Papers Relating To English Affairs in the Archives of Venice, Volume 7, 1558-1580, ed. Rawdon Brown and G Cavendish Bentinck (London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1890), pp.558-564, no.683; Mark Greengrass, Governing Passions: Peace and Reform in the French Kingdom, 1576-1585 (Oxford University Press, 2007), pp.123-153

See reports of 13 and 27 August by the Venetian ambassador in England, in 'Venice: August 1627, 11-19', in Calendar of State Papers Relating To English Affairs in the Archives of Venice, Volume 20, 1626-1628, (London, 1914) pp. 319-348

Pablo Ortego Rico and Íñigo Mugueta Moreno, ‘Kingdoms of Castile and Navarre’, in The Routledge Handbook of Public Taxation in Medieval Europe, ed. Denis Menjot et al. (Routledge, 2022), pp.120-154

Claudia Mineo, ‘Law, Litigation, and Power: The Struggle over Municipal Privileges in Sixteenth-Century Castile’ (Ph.D. thesis, University of California, Los Angeles, 2006), pp.55-6, 268

Rosario Porres Marijuán, ‘La Política Fiscal de Felipe II En Alava: El Estanco de La Sal de 1564’, in Poder, Pensamiento y Cultura En El Antiguo Regimen: Actas de La 1a Semana de Estudios Historicos ‘Noble Villa de Portgalete’ (Eusko Ikaskuntza, 2002), pp.47–78.

It was about 10% of indirect tax revenue, so must have been well under that proportion once direct taxes and other revenues were taken into account.

Mark Aloisio, ‘Salt and Royal Finance in the Kingdom of Naples under Alfonso the Magnanimous’, Medioevo Adriatico 3 (January 2010), pp.9–28.

E. William Monter, A Bewitched Duchy: Lorraine and Its Dukes, 1477-1736 (Librairie Droz, 2007), pp.43, 49, 119, 161

Matthew Vester, ‘Territorial Politics and Early Modern “Fiscal Policy”: Taxation in Savoy, 1559-1580’, Viator 32 (January 2001), pp.279–302

Richard Hellie, ‘Russia, 1200–1815’, in The Rise of the Fiscal State in Europe c.1200–1815, ed. Richard Bonney (Oxford University Press, 1999), pp.480–505

This is of incomparable depth and insight, a highlight on the platform

Fascinating. I look forward to part 2.